Spending the UAE summer indoors with a sick 3-year-old and a doctor’s warning to avoid the community swimming pool doesn’t leave room for many entertainment options. So, Netflix binges have been the activity of choice for a mother in her third trimester of pregnancy with little energy for much else.

Bored with the streaming platform’s limited selection of classic children's films, my husband and I preregistered and counted down the days until the launch of Disney+ in the UAE, and were thrilled once the glitches were fixed.

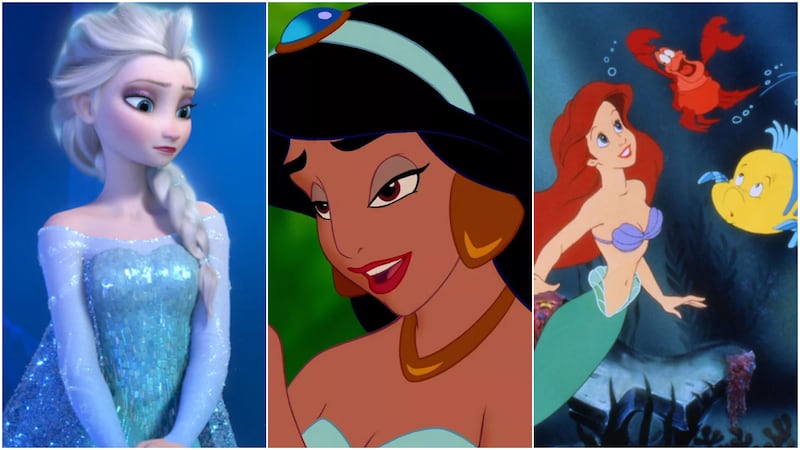

In the weeks since we’ve combed through all the classics, half of which were conceptualised long before I was born. We’ve witnessed the brutish Gaston harass Belle to become his trophy bride in Beauty and the Beast, and the impish, gold-digging Aladdin use deception to worm his way into Jasmine’s good graces.

My initial excitement over showing my daughter princess movies from my childhood has quickly waned. Now, through my 21st-century feminist lens and perspective as a mother, I can’t help but feel disheartened and dismayed with the way female protagonists were portrayed in these films — primarily as damsels-in-distress whose salvation comes through finding a handsome prince, sanctified with “love’s true kiss".

From Sleeping Beauty to Beauty and the Beast, finding the “kiss of true love” to break a curse forms a focal story arc in many of these movies. Kiss the girl is an entire musical track, sung by Sebastian the crab in The Little Mermaid, a film where the supposedly-strong female lead, Ariel is rendered voiceless, literally, due to Ursula’s curse. That climatic kiss becomes the cast of sidekicks’ obsession, usually animals or sea creatures, or in Belle’s case, talking teapots and clocks. Even in the much newer Frozen, Elsa’s feisty sister Anna can only be saved from her frozen heart curse by “an act of true love” — which is interpreted as a kiss.

Romance is the ultimate goal for these female characters — even Belle, who is introduced as a clever, library-loving bookworm, who inevitably finds happiness through falling in “love” with a rich man-turned-beast-turned-man-again who lives in a grand castle.

There have been some semi-positive role models. Mulan, which was released a decade after The Little Mermaid, finally portrayed a diverse female lead who is active and empowered, proving she’s just as good — actually, better — than any male soldier. That said, the storyline still includes problematic tropes about patriarchy, honour and marriage, and even Mulan miraculously finds romance while saving China from its enemies.

The only female-centred Disney movie I’ve seen recently that veers away from this troublesome storyline is Moana – a character who ventures across the sea to save her village, sans any romance or kisses.

My mother says I’m overreacting. And while I understand that these fantasies and narratives are reflective of a certain time, mind-set and vision of women, we must be honest about the fact that these films, some of which were originally released as early as 1930s, celebrate outdated ideals for women and girls.

Yet, walk into the little girls’ section of a clothing or toy store today, and you’ll be inundated with images of these very Disney princesses, clothed in decadent ballgowns that show off their trim waists, heaving bosoms and fair (or in Jasmine’s case, bronzed) skin. I can’t help but feel like my daughter is being commercially indoctrinated to idolise these fictional women — she begged me to buy a water bottle that depicts a group of these princesses, months prior to ever seeing their movies.

Times may have changed, but collaborations with Disney still depict these old, uninspiring characters — Belle, Ariel, Jasmine, Aurora and Snow White, on products. Rarely do we see Mulan, or Moana, or the lovable, curly-haired, glasses-wearing Mirabel Madrigal from last year’s hit Encanto, on little girls’ clothing or merchandise.

The women of colour who are sometimes flaunted on children's products include Jasmine and Pocahontas, connoting ethnic beauty with skin-revealing attire. When it comes to their clothing, the ensembles of Princesses Ariel and Jasmine, (who are aged only 16 and 15!) are particularly skimpy, emphasising a certain sexualised “ideal” when it comes to women’s curves. My daughter has become so smitten with Ariel that it’s brought on a full-scale obsession with mermaids — and with flashing her tummy. At the early age of 3, she has rejected her stylish one-piece swimsuits and now wants only to emulate Ariel. She even refuses to let us take her for a summer hair trim, insisting that looking like a pretty mermaid means having long hair.

These popular Disney princesses essentially share the same size-zero, hourglass body form, just with different hair and eye colours. At a time when the retail and beauty industries are making strides towards more body inclusivity and diversity, I can’t help but ask why we aren’t just as invested in refashioning the images and ideals ingrained in our girls from much younger ages?

The troupe of princesses from these films may be extremely popular, but they are icons from an era that should stay in the past, or as Ariel would sing, “part of that world” — a world that should have little significance to the ambitions and aspirations of girls growing up today.