As the first Pakistani to play the first South Asian superhero in the Marvel universe, Kumail Nanjiani is well aware of the weight he carries on his shoulders. But it’s not only in the areas of race and representation the star, 43, is feeling the pressure.

While the actor found himself making international headlines when he won the role of Kingo in Marvel’s latest superhero blockbuster Eternals, he created a bigger stir when he shared a photo of himself on Instagram looking spectacularly ripped, alongside the caption: “I never thought I’d be one of those people who would post a thirsty shirtless [photo], but I’ve worked way too hard for way too long so here we are.”

On the recent promotion tour for Eternals, Nanjiani was to be found in a thoughtful frame of mind when it came to his body shape, and the part his physical transformation might have played in the greater conversations being had around male body image.

“It is aggression. It is anger,” he told GQ of the connotations around sculpted bodies and gym culture. “A lot of times we are taught to be useful by using physical strength or our brain in an aggressive, competitive way. Not in an empathetic way. Not in an open, collaborative way... It’s about defeating. And that’s what the male ideal has been. Dominating. Defeating. Crushing. Killing. Destroying. That’s what being jacked is.”

Dina Zalami, a counselling psychologist at Thrive Wellbeing Centre by Dr Sarah Rasmi, says that in recent decades, men have started to become more exposed to male body image ideals through the media and film industries, as well as social media, "which depict the ideal man as physically muscular and buff”.

“These physical traits reflect the expectations for men to be strong fighters and protectors. The aesthetic ideal is linked to the functionality of their bodies.”

A brief history of men’s bodies

While women’s bodies have been put under the microscope for centuries, men’s bodies have largely escaped the same scrutiny. Although that’s not to say society hasn’t evolved and signalled expectations when it comes to the male form.

Whereas once larger, fatter body types were favoured as a way of displaying wealth and status, men’s idealised body shapes have changed throughout the years, with the most rapid onslaught – from decade-to-decade as opposed to century-to-century – emerging in the early part of the 20th century.

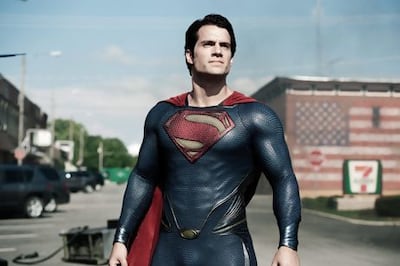

Trends around men’s bodies have long been subject to change: the Adonises of the Greek era, their muscular forms immortalised in marble; the idealistic proportions of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man; the femininity of the “macaronis” of the 1700s; the slender, cheek-boned perfection of Rudolph Valentino in 1920s Hollywood; the rise of bodybuilder Charles Atlas in the 1930s and '40s; the slim-fit of the '60s, which gave way to the even slimmer fit of the David Bowie and Mick Jagger-dominated '70s; the Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone-saturated '80s; up to the superheroes of the day such as Henry Cavill and Chris Hemsworth.

“While an ideal male body image has also been present in our collective psyche throughout history, it was not the only dominant standard applied to men’s worth,” Zalami says.

“Men’s worth has also been linked to other attributes, including their socioeconomic status and strong or tough personality traits – all traits that would facilitate their ability to take care of their families. So, while a certain body shape was desired, it wasn’t as much of a focal point as it was for women.”

Media, messaging, society and psychology: what influences the male form?

“Just like with women, body image issues amongst men don’t occur in a vacuum,” says Zalami. “They are influenced by many factors and vary when it comes to their intensity and impact on a person’s mental health.”

Biological, psychological and social factors have long influenced men’s relationships with their bodies. Plus the ongoing pandemic may have resulted in men “getting buff” as a way of controlling their immediate environment, in the absence of external control.

“During my five-year career in fitness, in this time I’ve found that men have gone from wanting to look overly buff to a more toned, slim physique. More like a fitness model than a bodybuilder,” says personal trainer and group exercise instructor Paul Holder in Dubai.

“Most guys focus on areas, such as wanting a bigger chest or bigger arms. I’ve also noticed a trend now for guys asking me for tips on how to get a better butt. I teach an abs and butt class and find that there are as many men attending as women.”

Men’s magazines with a focus on health and fitness, increased access to and knowledge about diet and fitness, the rise of “gym culture”, plus the effects of advertising and media have all combined to create, influence and promote recent male body standards. These, when considered alongside socioeconomic status – with good diet and fitness regarded to be a privilege of higher earners – help shape the picture of how and why men’s body standards are created.

“I think there’s always been a male body standard that is in a word ‘ripped’,” says social media strategist Hayley Hilton. “The only difference is that now men are surrounded by these images, and they aren’t just celebrity bodies. It’s their friends and people they know, so it turns up the pressure to fit in.

"One study showed that men who look at #fitspo content more frequently care more about their own muscles, so there is a correlation," she says. "We should be conscious of the content we’re consuming and how it’s making us feel. Notice if following an account is making you feel better, or worse, and unapologetically unfollow.”

What does it mean to be 'ripped'?

While being “ripped” means different things to different people, generally the word conjures up images of muscular arms and torso, as well as a six-pack.

In fact, a six-pack has become synonymous with the term, and a quick Instagram search yields more than 12 million posts dedicated to the physical attribute. But what is a six-pack and how is it achieved?

“Principally, acquiring a six-pack – or four-pack, or eight-pack if you’re lucky enough to have these genes – has a lot to do with your body fat percentage,” says Lina Shibib, clinical nutritionist at Medcare Hospitals & Medical Centres. “To expose your sculpted abdomen, you must first reduce your body fat. It’s critical to focus on both nutrition and exercise to safely and successfully decrease body fat. When it comes to reaching a goal, there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all solution – individual outcomes are influenced by genetics, body form, and build.”

All men and women have six-packs, or rectus abdominis muscles. Located inside the abdominal region, it is only by burning off fat that they start to become noticeable.

“When this muscle is exercised and layers of fat disappear from the abdomen, the exposed rectus abdominis muscle creates the look of a six-pack,” says Sushma Ghag, dietetics specialist at Aster Hospital Mankhool. “To accomplish a six-pack, muscle versus fat proportion should be in the 5 to 9 per cent range.”

The process is long and arduous, requiring constant vigilance around diet and exercise, as well as avoiding certain food groups, such as carbohydrates, and consuming larger portions of others, including proteins and lean meats.

“I would not have been able to do this if I didn’t have a full year with the best trainers and nutritionists paid for by the biggest studio in the world,” Nanjiani said of how he achieved his Eternals physique. “I’m glad I look like this, but I also understand why I never did before. It would have been impossible without these resources and time.”

Through toxic masculinity to body positivity

“In general, there is a lack of openness and discourse about the emotional and psychological issues men face,” says Zalami. “Our society is more adept at talking about women’s vulnerabilities than men’s. Given the toxic masculinity culture which shames men’s vulnerabilities, it is hard for many men to be open about their body image concerns and so much more.”

The phrase “toxic masculinity” may be relatively modern, but hypermasculinity as a concept is not, and the notion is inherently entrenched in male body image.

Toxic masculinity is the term used to describe cultural norms and traditional stereotypes that not only harm society, but also men themselves. Traits such as dominance, misogyny, violence, aggression, bullying and repressed emotions, as well as adages such as “boys will be boys” and “boys don’t cry”, are all considered psychologically damaging.

“Boys experience peer pressure where they believe they need to be strong, tough and athletic,” says Carolyn Yaffe, clinical psychologist at Medcare Camali Clinic. “In addition, society and social media promulgate a culture of masculinity associated with being psychically strong and fit. There are also myriad advertisements and public health campaigns urging weight loss and physical fitness.

“Within the last few years, we have seen body positivity promoted on television, social media and in magazines. However… men, often left out of this conversation by the media, are receiving different messages,” she explains.

“An example would be the popularity of superhero movies. These movies and characters are sending messages of what defines masculinity by encouraging a particular physique – being muscular and strong represent bravery and dependability. The fact is these types of bodies are unattainable and unrealistic. Men being self-conscious and bad about their bodies often makes them feel too vulnerable – it is truly a silent shame.”

Men’s relationships with their bodies is highly individualistic and, as such, experts recommend focusing less on comparison and external factors in favour of taking a more personal and inward-looking approach.

“What are they needing?” asks Zalami. “Approval, validation, reassurance, a sense of control? Once they understand the function of that pursuit or obsession, they can better address the needs behind it in healthier ways.” Meaning a greater understanding of why happiness might be contingent on body shape is necessary in order to reframe body or weight goals.

“When a client comes to me with a picture of someone they’ve seen on social media and tells me that this is the body they want, I say: ‘Great, but let’s use that as motivation, not as a goal’, because there are so many things that go into images you see online,” says Holder. “Feeling happier and more positive as a result of their training should be the main motivation. Not to look like somebody else.”