The distance from front door to desk is not far, but Ridha Moumni invariably takes more time than might be expected on the journey through the corridors of Christie's to reach his office — and then there are the days when he wanders the long way round.

It’s not at all a reluctance to get to work. More that beyond the distinguished stone facade flying the red flag of the world’s oldest fine art auction house, untold distractions abound.

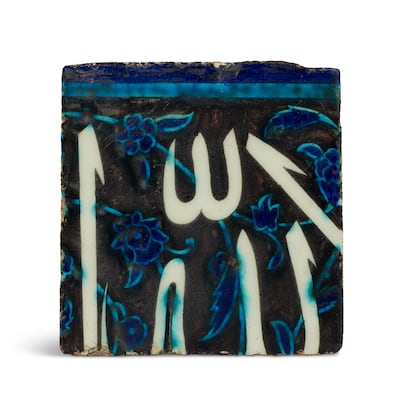

There are drawings by Lucian Freud and various bronzes of Rodin here, an Egyptian papyrus fragment from “Book of the Dead” there, and, Moumni’s personal favourite at the moment, a 16th-century ceramic tile featuring thuluth script and flowering vines made in Ottoman Syria or Palestine.

Once past all the diversions, his working days are a whirl of sourcing rare and valuable objects, meetings with collectors and curators, painstaking historical research, event planning, liaising with institutions and government ministries, and devising business strategy in the Arab world.

When Friday comes around, appetite still unsated, the art historian often strolls the 10 minutes from St James’s to Trafalgar Square to savour the after-hours exhibitions at the National Gallery.

“Going to museums is a hobby, going to see exhibitions is a hobby,” Moumni, 42, tells The National. “I feel really, really grateful that it’s also my work.

“Working here in a building that is an office space but at the same time a gallery space, where I can walk and see art every day when I come to this office, is very comfortable.”

Born in Tunisia, that passion has taken him around the world, via France, Algeria, Italy, the US, and latterly Britain, where his role with the renowned auction house is as deputy chairman of Middle East and North Africa.

In each encounter or project, he is ever ready when any possibility arises for him to promote Mena art and culture, to “make sure that my region is visible”.

“For Christie’s, hiring someone with my background means a new approach and comprehension of the Middle East, and new strategy for the region,” Moumni says.

As he points out some of the treasures in the current Christie’s sales catalogue, a dinner is being prepared for young patrons already amassing their own art collections.

But Moumni’s journey to this Grade II-listed building in London was a little more circuitous.

His early years were spent on the move because his father, Bouabid, was a Tunisian diplomat, shuttling young Ridha and his older brother Tarak between Tunis, Algiers, Paris and Marseille.

Looking back now, from a new office that is in a state of ongoing decoration, he is grateful to have been immersed in so many different cultures.

Among all the memories, though, there is none he can conjure as the reason for why his taste for art developed; the environment in which he grew up was not artistic, and there were no trips with his parents to museums or galleries.

But he liked to read about history, particularly the stories of Carthage, one of the most important cultural hubs of the ancient Mediterranean, situated in what is now the suburb of Tunis.

After setting out on an archaeological path, he gradually came to combine his love of the past with a love of art. “When I started studying in Paris, I really discovered art history. I didn’t even know it was something that I could study,” he says.

Ridha had initially thought of following his father into diplomacy and accepted an internship at Unesco. When ambitions of becoming an art historian instead began to emerge, his parents were sceptical.

Often those pursuing such a path come from affluence, which was not the case for the Moumnis, in spite of Bouabid’s diplomatic career.

“It was very risky,” he says of the decision-making. “I think it took my parents time to understand what I was doing, to see somehow that I could be successful in that field.”

But they recognised his determination and, after a few months, gave their approval with one condition: his mother, Khedija, insisted that her son see his studies all the way through to a PhD.

On the day that Moumni completed his doctorate in North African Roman Architecture at La Sorbonne University, Paris, his parents were in attendance and by then more than reconciled to the change in tack.

“When I got my PhD, did my first shows, went to the Villa Medici as a fellow of the French Academy in Rome, which was prestigious, and built a career — in the end, I think if you ask them, they are happy with my choices,” he says, all smiles, and he hasn't even mentioned the many honours and accolades garnered along the way.

His parents still live in Tunis, the setting of his proudest achievement as an art historian, a 2016 exhibition that stirred powerful memories of the country’s past and was profoundly moving for some visitors.

The priceless items in the display, L’Eveil d’une Nation (The Awakening of a Nation), included Tunisia’s 1861 constitution, the first in the Arab and Islamic world, and a text that completed the abolition of slavery in 1846, another first.

There were also royal collections belonging to the former Beys of Tunis, the rulers for more than 250 years, which had never been shown to the public before.

The exhibition came at a politically sensitive time as Tunisia marked its 60th anniversary of independence and sought to establish stability five years after a 2011 revolution.

“It’s a moment where Tunisians in general needed historical and cultural background,” Moumni says. “They needed to understand their identity from that perspective and to be exposed to their artistic heritage.

“Before this exhibition, people in Tunisia tended to overlook their pre-colonial past. Seeing visitors getting extremely emotive, seeing them cry sometimes, which I experienced, is very impactful and powerful.”

Visited by many schools and teachers, the exhibition left a permanent legacy in Tunis: a museum at the former royal Ksar Said Palace which had previously been closed to the public for decades.

If he could have a similar impact again, he would aim to counter a misconception arising from the actions of extremists in Iraq and Syria that Muslims are prone to deprecating and destroying cultural heritage, such as the ancient site of Palmyra — where he carried out fieldwork for a dissertation — which was subsequently desecrated by ISIS.

The prejudice dates back to colonial-era literature, Moumni says, but is exposed as false by his research into Arab art collectors who gathered antiquities such as Carthaginian relics in the 19th century.

“I would love at some point to curate a show on that," he says, "highlighting the tastes of Arab collectors, that they were awakened, were sensitive to art, were educated, and also understood the cultural dynamics of the west.”

Another theme of immense interest to him is the connection between art and politics during Tunisia’s 20th-century decolonisation from French rule.

Moumni’s desire to understand the political and cultural context behind an artwork means it can almost be hard for him to step back and focus on the raw aesthetic beauty at times.

He cannot choose a favourite piece or period of art, having been fascinated at various stages by Greek sculptures, Italian renaissance, British and French 19th- and 20th-century paintings, pre-Columbian art and modernism in the Arab world.

However, he derives appreciation not only from gazing at paintings and sculptures but the view of elegant town houses from his office. It perhaps bears recording that his interviewer’s sloppy handwriting elicited substantially less admiration.

Although no artist himself — Moumni wishes he was but “if you like watching beautiful movies, it’s not because you’re a director” — he enjoys moving in creative circles in both his working and social lives.

On two occasions, those connections earned him a credit and entry in the Internet Movie Database, once for an on-screen role in a film that was projected on to the facade of the Villa Medici, and once for contributions behind the scenes.

Self-effacingly, he laughs out loud when reminded of these achievements. “Because I am used to working in a creative field, you interconnect with a lot of creative people,” he tries to explain, somewhat abashed.

Moving to London from Harvard University, where he was an Aga Khan Fellow in the art history department, was another gamble because it meant swapping academia for the commercial world.

Moumni thought long and hard about the decision, but the pandemic and its working from home culture had sucked some of the life out of Harvard, and Christie’s offered the chance to see and learn new things.

Lockdown was “a moment that made me reflect a little bit about the sustainability of what I was doing,” he says.

At the auction house, he never tires of seeing the incredible and eclectic pieces that pass through the elegant building. A current “Art of Literature” display includes a first edition of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone signed by JK Rowling, as well as a 1663 copy of William Shakespeare’s works.

Visitors to the galleries are ushered to see Greek vases, several Andy Warhols and Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire by Pablo Picasso, all manner of jewellery, and a bronze sculpture of Hercules that recalls one of the great tales of classical literature.

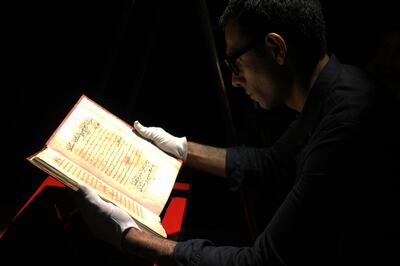

Moumni, though, has the privilege of sometimes viewing the items that are sold privately and never shown to the public.

“I’ve been in contact with objects in this auction house that I wouldn’t have seen anywhere else in my life,” he says. “It’s enriching, nurturing my maturity as an expert or a scholar or a person.”

He lives near Holland Park, a vibrant area of west London, and relishes all that the capital affords him professionally and recreationally.

“I love the neighbourhoods in London, the architecture, the museums, and how cosmopolitan the city is,” he says.

“And there is diversity in this workspace, also in the background of my colleagues here and the people I’m working with, that I find really enriching and enjoyable. I don’t know if this kind of set-up is possible in many cities in the world.”

As much as he adores the capital, travel now is arguably even more frequent than it would have been had he followed his father into diplomacy.

Though foreign forays were a regular feature of his childhood, he never takes them for granted, partly because those of his grandparents’ generation would barely have journeyed anywhere except perhaps Makkah.

Moumni has recently returned from a conference in Tunis when The National meets him, and is often in the Gulf because Christie’s has an office in Dubai. In fact, he is setting off for Saudi Arabia today for meetings about what he will only say is “a confidential project”.

“I never get tired of it,” he says. “I enjoy travelling because I am learning - and I love learning, seeing people from different backgrounds, new cultures and trying to better know them. Every time seems or feels like almost regenerating through that richness.”

The young Ridha poring over his history books might not have understood quite what he would one day end up doing but his older self is very pleased at where trusting his instincts, taking risks and following his passion led him.

Life, Moumni reflects, is full of discoveries and surprises. A bit like when he heads to the cafeteria to grab a drink and ends up spellbound for 20 minutes in front of, say, a large Van Gogh that has unexpectedly appeared en route.

“Magical moments,” he says, with deep satisfaction.