Inside the white chapel at St Teresa’s Effingham, row upon row of girls would pray on their knees twice a day during Mass, all except one small figure seated on a pew in their midst.

Ten-year-old Reem El Mutwalli, the only Muslim pupil at the Catholic boarding school, felt she could never escape the services each morning and night because her presence invariably interrupted the seamless symmetry of bowed heads.

“I didn’t kneel and that showed,” Dr El Mutwalli told The National. “I stood out. So if I was to ditch prayers or not appear then people would notice.”

Although far from her Emirates home, the young Reem soaked it all in – the "wonderful" atmosphere, smell of incense burning, the candles, the chanting and uplifting hymns that she still listens to at breakfast all these decades later.

It might, she concedes, seem an unusual choice by her parents, but Tariq and Buthaina’s generation believed in the merits of a convent education, and what safer place for their only daughter than an all-girls’ establishment run by nuns in the English countryside?

Now the respected scholar, expert in Arab culture and interior design consultant, known affectionately as Dr Reem, credits the years in Surrey with shaping her personality and even her principles. Living between two countries and two religions opened her eyes, she says, “to the need for us to accept the other and learn that we are not so different”.

Dr Reem, a naturalised Canadian with homes in Montreal, Dubai and London, has lived in many parts of the world but has never felt a complete belonging to any particular place.

Her old friend Sultan Sooud Al Qasimi, the renowned art critic, often teases her for what he describes as being “Iraqi in birth, western in education and upbringing, Arab in spirit and Emirati in passion”.

“I feel the statement is a poetic way of saying that after all these experiences and after all these years, I guess I believe in a shared humanity,” she says. “If anything, Covid has taught us that we are somehow connected. So all of these places that I tend to belong to in part create the whole of me.”

She moved to Abu Dhabi from Baghdad in 1968 as a five-year-old when her father was appointed legal and economic consultant to Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed, who at the time was crown prince of Abu Dhabi and whose father, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan, founded the United Arab Emirates three years later.

In many ways, child and fledgling country grew up side by side, and she describes her feelings of joy, fascination and privilege at being immersed in its history from such an early age.

Young Reem spent many happy years surrounded by the women and children of the ruling family, affording a unique insight into and love for the dresses and textiles of the UAE.

The interest would burgeon decades later into The Zay Initiative, a charity that advances cultural heritage through the collection, preservation and painstaking documentation of 1,000 historical garments and their often fascinating back stories.

Her ability to search for, identify and value traditional objects was inspired by her mother. Buthaina was the “original and real collector”, whose accumulation, not so much of items but of people, gave Dr Reem a life-long appreciation of art and culture.

The family home was open from eight in the morning until late at night with the ever-hospitable hostess welcoming “writers, authors, musicians, poets, politicians, librarians, university professors, ballet dancers, singers, you name it, they were all there”.

Among them were Lebanese master painter and calligrapher Wajih Nahle, the Palestinian artist Ismail Shammout, Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani, Emirati painter Abdul Qader Al Rais, and the Iraqi sculptor Mohammad Ghani and architect Zaha Hadid, many of whom presented their hosts with samples of their work as gifts.

“We met them constantly as I grew up – myself and my siblings – and got to know them and learn about them,” Dr Reem says. “This was how we were introduced to Iraq, to our culture, to our background as well as the rest of the Arab world.”

Since then, she has always had a longing for Iraq that is a sort of homage to the parents whose recollections infused in her an unconscious love for the country.

Smells, too, played an important role. The aroma of rosewater and that of kleicha (Iraqi date cookies) baking in her kitchen fill the air with nostalgia for Ramadans past.

However, it wasn’t until she made a trip to her ancestral homeland as a young professional that all these emotions and the facts Dr Reem had learnt from books and studies took on a new dimension.

After completing a degree in interior design and fine arts at Kansas State University, she returned to Abu Dhabi at the age of 21 to join the newly formed Cultural Foundation where she continued to work for the next two decades.

She was not only in charge of exhibitions but began to build the foundation’s own art collection, advised on artwork for members of the ruling family, initiated workshops and became deputy head of the arts and exhibitions department.

Not long afterwards, invited by the Iraqi artist and painter Layla Al Attar to lead a UAE delegation to the recently opened Contemporary Art Centre in Baghdad, she was escorted around the archaeological sites and museums of her birthplace.

“It was history coming to life,” she says. “I saw it for the first time with an adult’s point of view, not a childish one.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, though, the visit was to bring into stark relief the struggle of identity that Dr Reem thinks many of her generation are facing, and that those who came afterwards continue to grapple with.

Her welcome was warm, she recalls, but the Iraqis did not receive her as a compatriot, and those in the delegation did not regard her as being from the Emirates.

“It’s an excellent example of this fractured life we lead in the Arab world. Sometimes you laugh about the things that are truly hurtful,” she says, with a small smile.

“Maybe somebody else would have had issues. I don't know how I escaped that. I managed to harness all these feelings into something that was worthwhile.”

As part of her master’s degree in Islamic art, architecture and archaeology from SOAS, University London, she conducted a survey of Abu Dhabi’s forts, publishing the historic, architectural and social attributes of the country’s oldest and most significant building, Qasr Al Hosn, in a book that featured landmark interviews with members of the Al Nahyan family who last lived there.

But it was her position at the Cultural Foundation that was to become a cornerstone of her current role as guardian of traditional Arab dress.

There, Dr Reem began curating her personal collection, slowly amassed from gifts, auctions and markets far and wide and considered a formidable archive of Emirati women’s garments.

It became the focus of her thesis for a PhD, culminating in the publication in two bilingual volumes of Sultani, Traditions Renewed about the evolution of UAE women’s attire during the reign of Sheikh Zayed.

Years later, the collection became the core of the Zay Initiative, named after the Arabic word for dress and founded in the UK in 2018, with the addition of key examples from rural families and royalty in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Morocco, Egypt, Oman and other parts of the region.

“It’s a tedious and dry process,” Dr Reem says as she talks about the seemingly endless cataloguing. “It’s not the glamorous part of the work, but it’s the most important.

While the Zay Initiative is a way of continuing her passion and work as semi-retirement beckons, there is no doubt it’s a continuation of a theme that is threaded through her life.

“Why do I do this? Why do I feel the need to give back? I think it’s my upbringing, be it from my parents or from my education and formative years in the UK, something that is instilled,” she says. “It’s the need to be a productive person and to leave a footprint or leave something to humanity …

“Luckily, I found a way to do that. Not everyone finds it.”

For now, the onus seems to be on “semi” in the retirement scenario, given that Dr Reem barely sleeps and has little or no spare time such is the passion with which her work consumes her.

She looks back at what has been accomplished in recent years and says that it is “mindboggling”, crediting much of the enormous expansion to the dedication of a small team and the technology that has erased constraints such as time and geography.

Her daughter jokes at Dr Reem’s complaints that she can’t fit in any meditation sessions.

“You don't need to,” Mae tells her, “because you're always in the zone, doing your work. You are living a real-life yoga experience.”

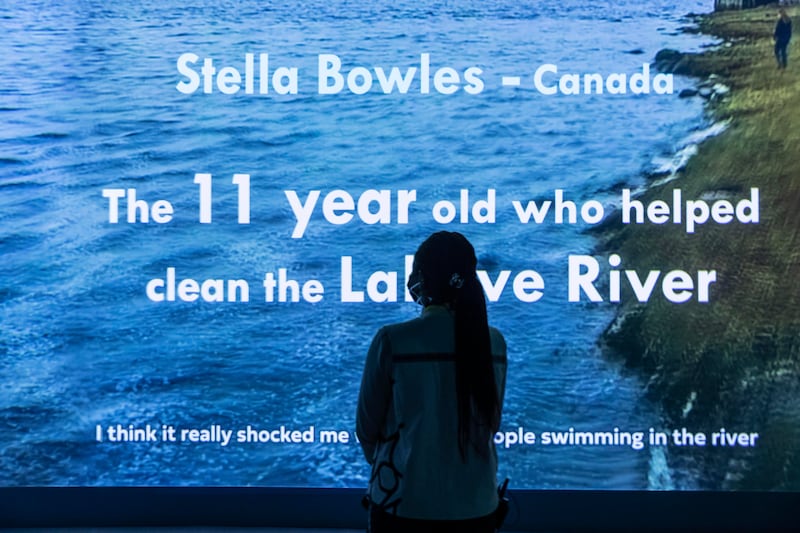

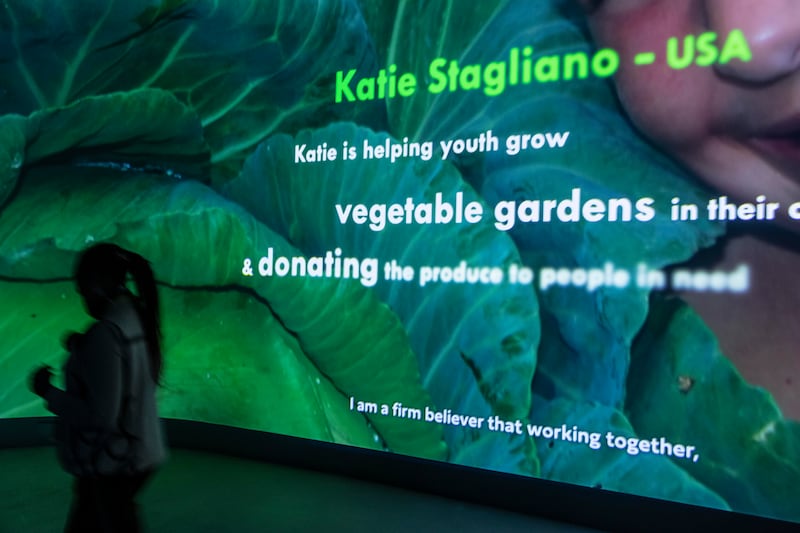

Anyone visiting the Expo 2020 Dubai Women’s Pavilion, in collaboration with Cartier, for which Dr Reem was lead curator at the first world exhibition to be held in the Arab region, couldn't fail to take in its ambitious remit, design and scope.

“The expo was my second PhD because it was four years of amazing learning experiences that one could write a whole book about,” she says.

“My role was to weave the Arab and Muslim perspective into a narrative that represents all women around the world. So we had to look and study the history of women’s movements, achievements, obstacles, aspirations and create an exhibit that captures the eyes and attention of the visitor in a 25-minute period; it is quite an endeavour.”

She was also behind the creation of “Draped in Heritage”, an ancillary but private exhibition to the Women’s Pavilion, for which 20 trailblazing women were photographed in their fields of expertise wearing historic outfits from the Zay Initiative collection.

Women of Dr Reem’s age intrinsically understand the value of the work, but she knows that reaching beyond them to the younger generation coming through requires a more modern, edgy approach.

Thinking outside the box and conscious of being a mannequin for what she is trying to achieve, she recently dressed the part and dyed her hair emerald green – her favourite colour – for a television interview.

“People think that culture and history has to be in a museum, an institution, old and stuffy in an academic format. I wanted to create a bridge between fashion trendiness, futurism, sustainability and heritage,” Dr Reem says of the appeal to a youthful audience.

“It is they who are going to be the right custodians to carry the torch forward.”

Her legacy would have been more in flesh than fabric if Tariq and Buthaina, fearing that their naturally independent daughter would never return home, had not steered the teenager away from ambitions of becoming a medic.

After Reem received an offer from the Royal College of Surgeons to study in London, they convinced her during a visit to relatives in the American Midwest to try a semester in Kansas, where she eventually chose the degree in interior design and fine arts.

“I think I would have loved being a doctor,” she says. “But it would have been a completely different life. I always say that interior design is 70 per cent psychology, 30 per cent design … so, in some ways, it is related to medicine.”

There are those who might regard her life’s work as trivial, but she argues that the region’s traditional garments have given her a small niche through which to create important cultural connections between different Arab countries and the UAE, and different Arab countries and the West.

If Dr Reem is yet to gain recognition for all she has given back to the countries that adopted her, she is quietly confident of standing out in the future as so often in the past. “History, for sure,” she says, “will credit me.”

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/HAXR62I45YVEYK2AV7ATANJPY4.jpg?smart=true&auth=73736d4d6be9891f99f5a94be4e3f9eb7d2490e012533854fee458b36af01f9c&width=800&height=600)

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/RZCFWR7GDMOF4MDEWV2QIXURV4.jpg?smart=true&auth=ae703e2132d22a94d220e52527e21222dde95617bf3f85c836bdba69f0c69fc5&width=800&height=592)

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/SHTWV2PWZ7LZSF3X3XYMF2L24Q.jpg?smart=true&auth=36a09674929edd0db736bfb3b577896354cdd1e5d3b699668bf86d5f034eaf10&width=800&height=1066)

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/W56RQHRQBU5GDOFRMK5MT2QJVE.jpg?smart=true&auth=76390596f9353aec34bc8460c43b331f14e931625e96b0688fe30d4ecbcf660c&width=800&height=1066)

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/7AYKSMY6HRAU4T7V4HMNXT5OHE.jpg?smart=true&auth=a390e62c53b509845de290284824480bae52e20b2bdd8d32416956fa2faf9cc9&width=800&height=1066)

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/UZNG447IRSSBYFEBNEXIZWHASA.jpg?smart=true&auth=d8991bab07d4e30bd141d70de5684fbe184611e28828d7d71d6b5b6bb56b5f8b&width=800&height=990)

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/HMLNEBPZ72DUHLKR54YMMJIOWE.jpg?smart=true&auth=7df5083392c71c5f710f191576e83b3fd70c84bb8cc0f541c068d77baee83f28&width=800&height=600)

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/GC4G3K2AII6VHS2AOLN7RCKMQA.jpg?smart=true&auth=d23c237398b4d043235c5529f666ac0ff069b263ef313c56af8aa39a3bd0459e&width=800&height=600)

![[©(c)Roland Halbe; Veroeffentlichung nur gegen Honorar, Urhebervermerk und Beleg / Copyrightpermission required for reproduction, Photocredit: Roland Halbe]](https://thenational-the-national-prod.cdn.arcpublishing.com/resizer/v2/JCH4STIRASDEEEZXPZYGUF6JWQ.jpg?smart=true&auth=c55ce3de81bb042c4b7c725788746862c0e592c211513d71401dd18db3a01249&width=800&height=600)