Most Damascene moments are dramatic by definition but few occur, as Atheer Awad's did, on an actual road that leads to the Syrian capital.

Her own turning point came when the vehicle she was travelling in with her family to register for university in Amman blew a tyre, hit an electricity pole and flipped several times.

The accident meant that Awad ended up in hospital and missed the window to sign up to study medicine. By the time she was discharged, the only degree option still open to her was pharmacy.

Though bitterly disappointed at the time, she has come to believe that there were greater forces at work on the day of the crash on Jordan Street.

“Let’s just say we put our car to the test,” Awad tells The National. “It was a complete wreck. We are lucky to be alive.

“But it wasn’t meant to be that I should study medicine. I took the car accident as a sign that the future held better things for me.”

As a result, she was steered into an unexpected career in which the eventual research fellow at University College London would amass numerous accolades: the Journal of Clinical Medicine's 2021 PhD Thesis award; an appearance on the Forbes 30 Under 30 list for Europe; reaching the finals in the Women of the Future awards 2022 in the science category; named as an International Pharmaceutical Federation FIPWise Rising Star for 2022 as well as one of the top 15 outstanding innovators under the age of 35 by the MIT Technology Review.

Her groundbreaking research is paving the way towards the creation of personalised medication that can be 3D-printed in patients' homes via smartphone — a potentially transformative innovation for those who find it hard to gain access to health care or don’t suit a one-size-fits-all service.

Born in Abu Dhabi and raised in Dubai by Jordanian parents, her hand was always first in the air in class when volunteers were sought to dissect animals at Al Mawakeb School in Garhoud.

It was an early display of Awad's enthusiasm for the sciences, particularly biology, and a prelude to her ambition of becoming a heart surgeon.

“I was so determined to make a difference and medicine is one of those industries that has a greater impact when it comes to changing people's lives,” she says.

“There is never a boring day with science because every day is a new learning experience.

“You come across things that you haven't discovered before or create new stuff by just playing around with things in the lab and mixing them together. It’s that sort of curiosity that motivates me.”

Back then, holidays were regularly spent visiting Jordan — trips that Awad still makes annually to catch up with extended family, go to weddings and indulge a soft spot for the local food.

“I love those traditional connections,” she says, “and still follow as many of these practices as I can, wherever I am.

“My faith helps a lot. But it isn’t easy trying to keep a balance between sticking to faith and being able to live in a foreign country.”

Moving to England wasn’t as daunting as it might have been without the unwavering support of her parents and four older siblings — a pharmacist, a consultant with whom she lived until recently, an IT specialist and a doctor.

“It is rare for all of us to be in the same country at the same time,” she says, laughing. “We travel between the three countries and there is always at least one of us living in each of the three. That makes it interesting for my parents, who get to travel everywhere.”

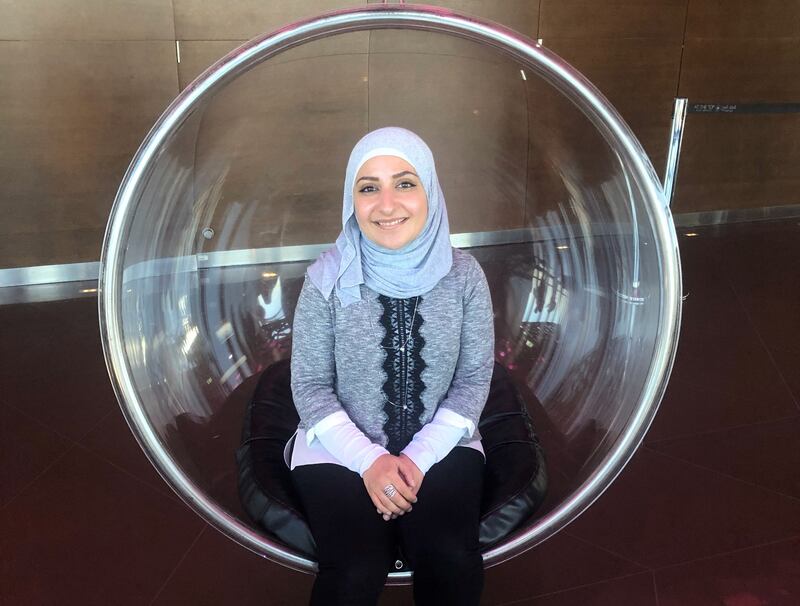

Awad herself, now 29, is a keen traveller and has put on her bucket list the wish to visit every country in Europe before turning her sights to other continents.

She fell in love with Turkey after a trip to Cappadocia, the semi-arid central region known for its “fairy chimney” rock formations, and particularly enjoys explorations on foot.

London, however, holds a special place in her heart, where there is, she points out, a big Jordanian community.

“I have a lot of friends I consider my second family. They’re a mixture of scientists, people outside work, and others with Jordanian or Arab heritage. That keeps me connected to my roots and it is one of the beauties of London — it’s international.”

But she calls Dubai home and makes many happy returns to Living Legends, a newly developed 14 million-square-foot community on the outskirts of the city where her parents still live.

Part of the appeal of the emirate, it should be said, is the chance to hit the luxury shops. Dior and Prada are favourites — her handbag collection alone extends to “about 40 or 50 … I’ve lost count” — and the Swarovski-encrusted mobile phone she takes everywhere is a particularly prized purchase.

Invariably, though, one of the first stops is to fill up on luqaimat, known as awama in the Levant. She has sampled the sugary doughnuts wherever she finds them but maintains that the ones whipped up for as long as Awad can remember by her mum, Hanan Swais, “are the best”.

They were an abiding taste of a childhood in which the extroverted Awad, left to explore her own interests by her father, Jamal, an electronics retailer, and Hanan, a homemaker, played the piano exuberantly if not with any notable proficiency and went on Scouting expeditions.

There was never an expectation that she would follow in the footsteps of any of her siblings but the desire to pursue medicine was strong nonetheless.

“It wasn’t until we were discharged from hospital [after the car accident] that I realised I had missed the deadline,” she says. “There was no going back in time. I just thought: ‘What’s the next best option?’

“That’s why I always say I did not choose pharmacy — it chose me.”

Despite a reluctant start, Awad’s enthusiasm grew throughout a five-year degree at the private Applied Science University in Amman as she gained insight into the extent of what pharmacists could actually do.

“I started looking at pharmacy as having a bigger impact than I had previously thought,” she says.

“People sometimes look at pharmacists as if they are beneath or less important than doctors when, in fact, they do most of the work behind the scenes.”

Little by little, with the consolidation of hours of satisfying sessions spent researching in laboratories or learning about the differences in the properties of various drugs, it dawned on Awad that she had stumbled across her calling.

Which is not to say that she appreciated being treated as little more than a saleswoman while doing work experience in a community pharmacy during the degree course.

“People assume that the pharmacist just takes the prescription and gets the medication without doing anything else,” she says. “There is a misconception.”

The experience hardened Awad’s resolve to focus on research rather than the direct, community-facing side of the profession.

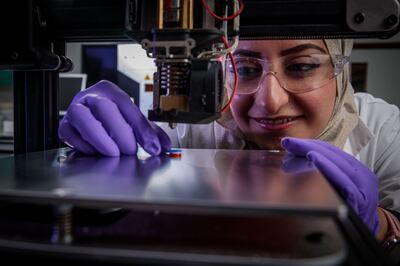

After graduation in 2015, she embarked on a master's in pharmaceutics and drug design at UCL, where she learnt about 3D printing during an end-of-year project with her professor, Abdul Basit.

She was inspired to keep working with the Basit Research Group within the School of Pharmacy to undertake a doctorate specialising in using the drug-delivery technology in the manufacture of medicines.

“I’ve always been interested in technology so it grabbed my interest immediately,” says Awad, who is still a research fellow with the group.

Weekends when she is not working are spent dining with friends, indulging her obsession for Harry Potter — “I’ve watched all the films multiple times” — and baking. Coffee cake is her speciality and made a well-received appearance at her professor’s 50th birthday.

“My friends loved it so much, I’ve had to make it several times,” she says. “I’ve moved on to cake decoration as well.

“I do like experimenting with baking and cooking. I think there are similarities between baking and science.”

She doesn’t rule out applying to appear on The Great British Bake Off television show but, for now, Awad’s ambitions are confined to the lab.

“I want to make a change,” she says. “I don’t want 3D printing to stay a theory. I want to see it being implemented and taken up by healthcare agencies.”

Most recently, Awad has been printing tablets with Braille and moon patterns on their surfaces for visually impaired patients, or changing their shape, size and colour so that children or those with limited capacity find them easier to take. She has also been researching how to combine several medications into a single pill.

One of her team’s successes has been in creating tablets that can be swallowed without water. Manufactured in partnership with pharmaceutical 3D-printing specialist FabRx by melting powder particles with a laser beam and using heat, the porous product dissolves on the tongue.

She talks about how 3D printing allows alterations of a fraction of a milligram, making medication much more tailored and precise than the standard variety available off the shelf.

“Every person is different and our bodies do not react the same,” Awad says. “The requirements when it comes to medication differ, and sometimes they differ within the same person, depending on the disease progression.

“We can also take patients’ preferences into consideration. That’s important when it comes to children or elderly patients. Often children refuse to take medicine because they don't like the taste, the shape isn't appealing or the pill might be too big.”

While 3D printing for customised pharmaceuticals has yet to be introduced commercially in the UK, Awad’s UCL team has managed to convert a smartphone into an on-demand 3D drug printer with an app that could be used in remote GP surgeries and even at home.

“We’re not far from the industry adopting 3D printing, probably in the next two to five years,” she says. “Approval will have to be on a medication-by-medication basis because each medicine could behave differently to the same technology, depending on its properties, and the 3D-printing technologies themselves differ.”

Awad's passion for her work is tangible. The British-American analytics company Clarivate clearly thought so when last month listing her on its influential Highly Cited 2022. It was a remarkable achievement for such a young scientist to appear among fewer than 0.1 per cent of the world’s researchers across 21 fields.

Such recognition is welcome but, she says, the many “titles are more of an assurance that I am on the right track and that my work is important”.

“That’s the driving force to keep me moving forward and become even more ambitious to try new things,” she says.

One of her guiding principles is that researchers should be brave and adopt different approaches because even the most “ridiculous” ideas can be turned into brilliant inventions or innovations.

As she has been known to opine, not all scientific breakthroughs happen through planned research: “Sometimes, you come across things by accident.”

Given the route into her career in pharmaceuticals, it could be said that Awad started very much as she meant to continue.