Lisa Hepner has spent the last 30 years trying to outrun her diabetes.

But it’s not working.

She is now dealing with complications of the disease, decades after being assured a cure was around the corner.

More than 10 years ago, Ms Hepner, with her husband Guy Mossman, decided to channel her hope and frustrations into documenting that search.

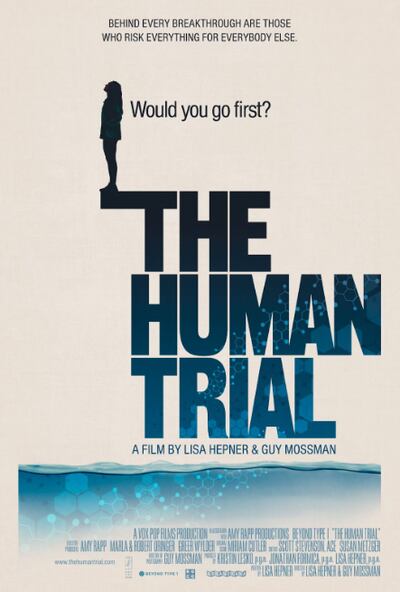

Their film, The Human Trial, follows one study from the outset of its approval for human trials in 2012, to its culmination a decade later, to show how tantalisingly close a cure has become.

It tells Ms Hepner's own story and follows the highs and lows experienced by two of the participants in what was only the world's sixth embryonic stem-cell trial.

The study aimed to find a cure for type 1 diabetes — a condition under which the body's immune system attacks and destroys the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin, which means sufferers must inject the hormone regularly to control the level of glucose in their blood.

Too much sugar can lead to complications such as heart or kidney disease, nerve damage, and various problems with the feet, mouth, eyes, hearing and mental health. But too little can result in unconsciousness — and even death.

About five million die each year from the disease, which affects 415 million people around the world.

Fewer than half, 46 per cent, are undiagnosed, according to diabetes.co.uk.

In the UAE, where the prevalence is among the highest in the world, as many as one in five people suffer from diabetes. That number is expected to double by 2040.

Type 1 diabetes is different from type 2, where the body does not produce enough insulin, or the body's cells do not react to insulin.

The diagnosis

Ms Hepner’s journey with managing her diabetes began in Edinburgh in the early 1990s when she was a new student living in a strange city.

“I was very thirsty. I had a huge gallon of water beside my bed, which you just think is normal. You don’t know what’s going on,” the Canadian told The National.

“Diabetes wasn’t in my family.

“And I was getting up to pee four times a night and then I was eating, but I was constantly hungry. I was craving sweets, which is counterintuitive. So I thought it was the flu.”

The only reason the disease was discovered early was because she had to give a urine sample as part of a preliminary physical examination.

The sample contained sugar, or glucose — a red flag — and she was sent to a specialist, who confirmed the diagnosis.

Her early conversations were at once reassuring (“don’t worry, a cure is five years away”) and alarming.

“I was told by my doctor he needed to check my feet. I said ‘why are you doing that?’ He said ‘oh well, diabetes is the leading cause of amputation in Britain’.

“I was like 'oh, welcome to the party', you know.”

Fast-forward 31 years, Ms Hepner's condition remains challenging.

If anything it was easier back when she was first diagnosed. She was in what is known as a “honeymoon phase”, because her body was still creating at least some insulin before her body destroyed the cells that produce it.

But it was still scary and difficult to manage. And it has become increasingly more so over the years.

The daily decisions

“I make 180 decisions a day just to stay alive, that’s average for someone with type 1 diabetes, insulin dependent,” she says.

“You are on this drug that can be lethal and you are constantly walking this tight wire act.

“And the 180 decisions a day we make, sometimes I know they are profound and I have to give myself sugar. Other times they are innate at this point, but it doesn’t mean it is easy.”

She knows when her blood sugar is too high, too low, falling or rising. She hardly ever feels well.

About 25 per cent of the time she is just trying to feel better. And mostly she is tired.

She injects insulin not only to cover her meals, but hormonal fluctuations and even stress. The simple act of climbing the stairs affects her blood sugars to the point she has to consider whether she should eat a banana before she does it.

“I wish I could say it gets easier. It doesn’t get easier. It gets harder. Because now I am dealing with the complications. I have retinopathy in the eyes,” she said, referring to damage at the back of the eye that can lead to blindness.

“I have a statistic which is very important. In 2019 they did a study and they said of people who used all of the devices, like I wear, only 20 per cent had a normal blood sugar. A normal range. And that’s with all the devices. So I find it stressful.

“I had a low blood sugar the other day. I felt terrible. It was in front of my young son, Jack. I know that he worries about me. He said to me the other day ‘mummy, don’t die’. I said ‘I am not going to die’. He’s seven and a half.”

Yet throughout all of this, she has forged a successful career.

After a stint in journalism following university, she discovered her passion: non-fiction.

She joined New York Women in Film and Television group and later co-directed a documentary in 2004 about women peacemakers.

Documenting the search for a cure

The Human Trial was to all intents and purposes her directorial debut.

She got the idea after reading an article in The New Yorker, which documented a clinical trial that was the precursor to the type of science on which it focuses — stem cells.

“The journalist was writing about the patients in the trial as well as the researchers. And of course he had written it five years after the trial. So he had a story that was all buttoned up,” she said.

She wanted to begin at the beginning and follow the progress in real time.

Little did she know the story would take 10 years to tell and take the team in search of investment as far afield as Riyadh.

And there was a false start — a study they documented for two years which failed to make it to human trials.

It was disappointing, but these things happen in research. So she began again, and with the help of experts found a promising study on which to focus.

The researchers at San Diego-based company ViaCyte received the go-ahead from the US Food and Drug Administration for human trials on the second day of shooting.

The science was extraordinary — groundbreaking, even, said Ms Hepner, who narrates the documentary.

“What these guys are doing, and what is now working, is they have programmed a stem-cell line, a five-day blastocyst, an embryonic stem cell, which would have been incinerated otherwise,” she said.

“In 2005 these researchers programmed this stem-cell line to become beta cells, insulin-producing cells. So they had to reprogramme it and work on it and create this pancreatic cell line … which is kind of amazing.”

They took the cells, which they placed into a pouch resembling a credit card, and placed them into a human being.

The plan was that over time the cells would mature into insulin-creating cells and start production.

“That means the person who has diabetes would no longer have to inject insulin. And their life would be a lot better,” she said.

Except it didn’t work in the first two people. So the researchers tweaked the protocol, using gene-editing to change the stem-cell line, which helped it evade the patient’s immune system, which had recognised the cells as foreign in the first two study subjects.

“It’s so cool. The cells work in a Petri dish and they are just testing it in humans,” she said.

And it seems to be working in people, too. But only time will tell.

The future

A cure now appears genuinely in reach.

“I think we filmed a team of researchers who handed the baton to a company that will find a cure,” said Ms Hepner.

“Science is incremental. Progress is incremental. And the groundwork that these guys laid, and the groundwork previous teams laid paved the runway for this to take off … I do believe it’s going to take off.”

Ms Hepner thought about participating in the trial herself. They discussed it but she ultimately decided it would be too much.

“It was quite intense,” she said.

She desperately looks forward to the day she no longer has to worry about her blood sugars.

And for the first time in the 31 years she has battled the condition, the cure does genuinely seem to be five years away. But how widely available it will be at the point remains to be seen.

There are probably other people who will need it more than her. So she may not be at the front of the queue.

“But I will definitely be in the line,” she said.

The Human Trial was released last summer and is now available on iTunes, Amazon Prime and Google Play.