Can photography depict human tragedy without showing those who suffered? Dia Mrad, a young architectural photographer in Beirut, believes it can.

Earlier this year, on a morning at sunrise, Mrad photographed the remains of the grain silos in the Beirut port. The ruins of this towering modernist structure, which stands at ground zero of the August 4 blast, gesture towards the devastated city.

In one image, the gutted building is mirrored in the flat, rippling sea water. In another, the endless rows of white cylindrical concrete piles, visible from the silos’ outer wall, serve as the backdrop for a flock of birds. They have gathered around the building to pick on the remaining grains, which flow out of the punctured structure like sand dunes.

For Mrad, these ruins should be considered a monument that protected the city. “The silos saved Beirut’s western districts from total destruction, and it absorbed up to 10 per cent of the damage in the hardest hit areas,” he says. Today, only the western wall remains.

As such, Mrad’s ensuing series of photographs, which was on view last month at the Arthaus Beirut hotel in an exhibit titled The Road to Reframe, aims to show this duality. In Part 1: The Dark Side of the Boom, the photographer studies innards of the silos’ remaining wall. In Part 2: The Desert of Beirut, he portrays the silos from the other side, its white paint and perfect curves unperturbed by the blast.

The images are rife with violence: the silos’ shredded edges of reinforced concrete look like a ripped linen fabric. But there is also a sense of calmness: the curves of the white cylinders are interrupted by the dunes, which have their own organic buoyancy.

But what impresses most in Mrad’s photographs is the disorienting manner in which he captures the scale of the building. To help achieve this effect, the images were shot on a medium format Fujifilm 50S megapixel camera, using a 17-millimetre wide lens. “It’s the widest possible shot that is available today without distortion,” he says.

The images were ordered chronologically for the exhibition, and captioned according to the time they were taken. “I wanted to create an immersive experience, so that the viewer feels they are walking through the grounds like I did,” he says.

It is a busy time for the self-taught photographer, who originally hails from Ras Baalbek, in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. His first solo show at Arthaus Beirut is set to travel overseas later this year. Last week, he was in Baalbeck installing a three-day exhibition at the historic Palmyra Hotel opposite the Roman ruins to coincide with the annual Baalbeck International Festival.

“I am looking forward to exhibiting close to home,” he says. “When I visited the silos, I had the same feeling I got from the ruins of Baalbek.”

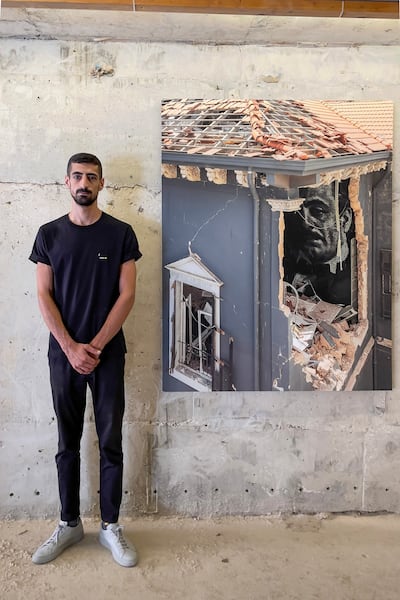

Mrad, 30, shot to fame online last year for his images of Beirut’s heritage homes that were destroyed by the August 4 blast. His vanishing world of hidden palaces was featured in Vanity Fair magazine, which has showcased some of the world’s most influential photographers.

Among his better-known photographs is one of the 19th-century Villa Mokbel on Sursock Street, which he took from the balcony of an adjacent building on August 5 last year.

The home was ripped open at the corner, revealing a mural of Lebanese poet Khalil Gibran. “I was so surprised to see his face,” he says. The wall collapsed half an hour later.

Mrad began documenting Beirut’s heritage homes in 2019. The young photographer originally trained as an architect at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, which is known in Lebanon for its lively cultural heritage programme. But there were few opportunities in architecture when Mrad graduated in 2017. “Instead, I developed my passion for photography,” he says.

A family trip to France and Italy fuelled his interest in preserving Beirut’s architectural heritage. He was struck by European efforts to conserve traditionally built environments. “I was jealous of what they had and how they were doing things,” Mrad says.

Upon his return, he began photographing the traditional homes of Gemmayze and Mar Mikhael. These adjoining districts around the Beirut port are emblematic of the city’s cosmopolitan identity, and were hubs for the city’s creative and hospitality sectors. But the area was neglected by real estate developers in Lebanon’s post-war years, thus preserving much of its original architecture.

“We have so many architectural styles. The traditional homes built before the 1920s often blended international styles with local architecture,” says Mrad. “I wanted to understand the vibe of the street, and why every street felt so different.”

Then, while working as a photographer for a property developer, he gained access to little-known views of Beirut’s skyline, from private high-rise apartments. This gave him new angles from which to document the city’s heritage homes. “Everyone thinks I shoot with a drone, but it’s from balconies. I don’t even know how to operate a drone,” Mrad says with a laugh.

Mrad gained an Instagram following, which grew at the start of the pandemic. But the real attention came after the Beirut blast.

On August 4, Mrad was riding through Mar Mikhael, and was propelled off his Vespa by the explosion. That same evening, and in the following days, Mrad would retrace his footsteps before the city’s destruction, documenting the damage to the homes he had so cherished.

Mrad attributes the success of this series to the fact he could publish fresh comparisons of the homes before they were destroyed.

“It was as if I had shot the buildings hours before and hours after the blast, so you could see the real extent of the damage” he says.

Journalistic or documentary images of the blast highlighted the humanitarian toll of the catastrophe. There were photographs of dust-covered and injured civilians roaming through smog, or of babies born in shattered hospitals.

But Mrad’s images stand out for their stillness, and the near absence of human life. “The damage that was evident to the architecture was the best way to show the damage and what happened to us,” he says. “It is more effective than showing people who were injured.”

Rather, photography has allowed Mrad to capture what he believes is at stake for the city’s identity. “The social fabric has been torn apart. We’ve lost the life around these buildings, I don’t know if we can ever recover it.”