A shackled tree, strange half-human creatures and a shimmering oasis. Across three different rooms, these artworks in Abu Dhabi Art’s Beyond: Emerging Artists programme tell stories of place and people in distinct ways.

Dedicated to rising talents from the UAE art scene, the programme has been curated this year by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, who also worked on the National Pavilion UAE presentation at the Venice Biennale in 2019.

'Too Close to the Sun' by Maitha Abdalla

At Manarat Al Saadiyat, each project for Beyond: Emerging Artists has been given the immersive treatment. Stepping into Emirati artist Maitha Abdalla’s Too Close to the Sun installation, for example, feels like being transported into an eerie domestic space.

Aglow in pink, the space’s painted walls are an allusion to the bathroom tiles of the artist’s childhood home. Hanging from them are Abdalla’s paintings of animals from Emirati folklore, flanked by shower curtains.

Towards the back of the room is a window looking out on a video installation, where the artist is seen roaming the forest and performing what appear to be rituals. In one instance, Abdalla marks a circle around herself on the ground before stepping out of it. The act represents a break from convention or “stepping out of boundaries”, the artist says.

This urge repeats itself in many of her works, including her performances, where the artist dons papier-mâché heads of animals and mimics their poses. “I cover the face as a way to show that there is still shame in attempting to do something different or out of the box,” she explains.

The inspiration of the video work at this exhibition is as forbidding as the setting. In Arab folklore, the spirit, or Sila, is a shape-shifting hybrid creature which lures desert dwellers and wanderers to their deaths. Abdalla draws from a particular version of Sila’s story, in which she marries a man and bears two of his children.

“One night, she saw lightning and took it as a sign to return to the wild, back to her clan, so she did,” Abdalla says. “The whole exhibition is around that attempt to bring out that wild nature. It’s about women who are doing things differently.”

Yet the artist is reluctant to define this wildness in one way or another. While her works express her own personal experiences, she says she leaves room for meaning to traverse into other points of view. “I’m a storyteller. I don’t give people advice on what is wrong or right. There’s no winner in my work … I want people to enjoy the story and interpret it in their own way.”

Instead, she relies on what she calls the “duality” of existing on the fringes. “Are you in the brightness or are you burning? That’s what the title and the work is about.”

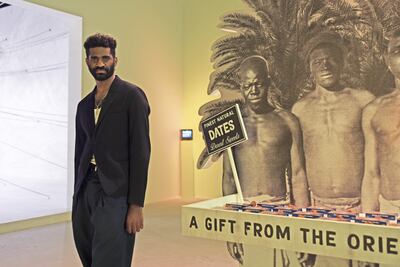

'The World Was My Garden' by Christopher Benton

Christopher Benton’s The World Was My Garden, meanwhile, explores uncomfortable histories, specifically the link between date palm cultivation and slavery in the Gulf.

In the latter half of the 19th century, as many as 800,000 people were torn from their homes in Africa and brought to the Gulf, including Oman, Bahrain and the UAE, as slaves, working as pearl divers or on date farms, furthering the two biggest industries in the region at the time.

“It was an inflection point where the growth of capital really exploded and necessitated even more labour than before,” Benton says. “You can see how it leads up to this contemporary moment.”

Benton showcases glimpses of the Arab slave trade through a three-channel video playing scenes from markets in Zanzibar from around 1860 to 1910, where people were sold and then sailed off to the Gulf.

The artist, who is currently completing a postgraduate programme at MIT, has often investigated labour and capital in the Gulf. His previous works include a collaborative film project with local tailors in Dubai’s Al Satwa neighbourhood which captured their daily lives, and his installation How to Rest, in which he repurposed chairs used by shopkeepers to sit on Dubai’s pavements during the winter.

For The World Was My Garden, the artist’s purview gets broader, bringing in histories from his native US as well. Outside of the Middle East, in the early 19th century, the Coachella Valley in California had the largest date industry in the world, affecting the Gulf region economically.

“Once America figured out how to produce its own dates at an industrial scale, it really affected the industry in the Gulf,” he says. While the US date farmers marketed their product as “cleaner” than the ones from the Middle East, he says they were more than willing to promote the fruit with campaigns featuring women in orientalist garb. “It was a total fantasy of what Arabia is.”

Perhaps the most striking work in his presentation is a chained Medjoul date palm hanging from the ceiling. It is a brutal image, even under the bright lights of the exhibition hall, and conjures visions of historical atrocities of which little documentation exists.

“There’s something violent and sad about uprooting a tree. At the same time, art has the potential to be of a history, a system, or a speculative future,” he says.

A few have questioned him digging up a tree for the temporary installation, but the artist hopes it is the idea of the piece that will resonate. “It could be seen as spectacle, [but] I hope the gesture creates an encounter for the viewer to emotionally relate to a lesser-acknowledged history here in the Emirates. One could tell you a story or one could show you an image, but the symbolic power of an evocative object can have the most impact and help create a memory,” he says.

He is currently in talks with a Sharjah institution to see how the palm could be used for handicrafts, and arish — an architecture technique using palm leaves, after the programme.

'Neptune' by Hashel Al Lamki

Finally, Hashel Al Lamki’s turquoise landscape Neptune is a gateway to another world, one with paintings of amorphous, glittery dunes, pools of water, and interiors. His abstracted paintings refer to Al Ain, a popular place for weekend retreats for Abu Dhabi residents.

“The scene that is depicted here is the landscape, including man-made landscapes like Al Ain. I talk about the relationship between Abu Dhabi and Al Ain, which is seen as a kind of exotic planet on its own,” he says.

“What’s interesting about Al Ain is that Jebel Hafeet, the highest peak of the emirate, is there. In my research, I learnt that the tectonic plate was separated from Africa and moved here, and it remains in constant motion. So there’s this idea of movement and transformation in these works,” he says.

Though very little is recognisable in terms of place or geography in these paintings, they offer an exploration into colour and light that the artist has been developing.

“I’m responding to density, volume and materiality,” he says. “In my process, I often refer to the natural resources in the region, including Oman and Morocco, where I have family connections. I grew up watching people making pigments and producing souvenir items, but these are industries that are slowly dissolving. So my pigments are collected from those places and artisans, and I use the process of natural dyeing to create the paintings.”

Neptune’s centrepiece is an arrangement of totemic sculptures where the artist has combined various materials, including discarded batteries, popcorn and stickers that stick out as rods from concrete pillars.

Though the works of Abdalla, Benton and Al Lamki are markedly different, they are bound by their connection to the UAE, not only in the artists' completion of the Salama bint Hamdan Emerging Artists Fellowship programme in years past, but also in demonstrating the myriad concepts that can be cultivated by artists in the country.

Beyond: Emerging Artists is on view at Manarat Al Saadiyat until December 4. More information is available at abudhabiart.ae

Normcore explained

Something of a fashion anomaly, normcore is essentially a celebration of the unremarkable. The term was first popularised by an article in New York magazine in 2014 and has been dubbed “ugly”, “bland’ and "anti-style" by fashion writers. It’s hallmarks are comfort, a lack of pretentiousness and neutrality – it is a trend for those who would rather not stand out from the crowd. For the most part, the style is unisex, favouring loose silhouettes, thrift-shop threads, baseball caps and boyish trainers. It is important to note that normcore is not synonymous with cheapness or low quality; there are high-fashion brands, including Parisian label Vetements, that specialise in this style. Embraced by fashion-forward street-style stars around the globe, it’s uptake in the UAE has been relatively slow.

Armies of Sand

By Kenneth Pollack (Oxford University Press)

MATCH INFO

Champions League quarter-final, first leg

Ajax v Juventus, Wednesday, 11pm (UAE)

Match on BeIN Sports

Common OCD symptoms and how they manifest

Checking: the obsession or thoughts focus on some harm coming from things not being as they should, which usually centre around the theme of safety. For example, the obsession is “the building will burn down”, therefore the compulsion is checking that the oven is switched off.

Contamination: the obsession is focused on the presence of germs, dirt or harmful bacteria and how this will impact the person and/or their loved ones. For example, the obsession is “the floor is dirty; me and my family will get sick and die”, the compulsion is repetitive cleaning.

Orderliness: the obsession is a fear of sitting with uncomfortable feelings, or to prevent harm coming to oneself or others. Objectively there appears to be no logical link between the obsession and compulsion. For example,” I won’t feel right if the jars aren’t lined up” or “harm will come to my family if I don’t line up all the jars”, so the compulsion is therefore lining up the jars.

Intrusive thoughts: the intrusive thought is usually highly distressing and repetitive. Common examples may include thoughts of perpetrating violence towards others, harming others, or questions over one’s character or deeds, usually in conflict with the person’s true values. An example would be: “I think I might hurt my family”, which in turn leads to the compulsion of avoiding social gatherings.

Hoarding: the intrusive thought is the overvaluing of objects or possessions, while the compulsion is stashing or hoarding these items and refusing to let them go. For example, “this newspaper may come in useful one day”, therefore, the compulsion is hoarding newspapers instead of discarding them the next day.

Source: Dr Robert Chandler, clinical psychologist at Lighthouse Arabia

Tour de France

When: July 7-29

UAE Team Emirates:

Dan Martin, Alexander Kristoff, Darwin Atapuma, Marco Marcato, Kristijan Durasek, Oliviero Troia, Roberto Ferrari and Rory Sutherland

Emergency

Director: Kangana Ranaut

Stars: Kangana Ranaut, Anupam Kher, Shreyas Talpade, Milind Soman, Mahima Chaudhry

Rating: 2/5

The rules on fostering in the UAE

A foster couple or family must:

- be Muslim, Emirati and be residing in the UAE

- not be younger than 25 years old

- not have been convicted of offences or crimes involving moral turpitude

- be free of infectious diseases or psychological and mental disorders

- have the ability to support its members and the foster child financially

- undertake to treat and raise the child in a proper manner and take care of his or her health and well-being

- A single, divorced or widowed Muslim Emirati female, residing in the UAE may apply to foster a child if she is at least 30 years old and able to support the child financially

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EName%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESmartCrowd%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2018%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounder%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESiddiq%20Farid%20and%20Musfique%20Ahmed%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDubai%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFinTech%20%2F%20PropTech%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInitial%20investment%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%24650%2C000%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ECurrent%20number%20of%20staff%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2035%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestment%20stage%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESeries%20A%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EVarious%20institutional%20investors%20and%20notable%20angel%20investors%20(500%20MENA%2C%20Shurooq%2C%20Mada%2C%20Seedstar%2C%20Tricap)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

AndhaDhun

Director: Sriram Raghavan

Producer: Matchbox Pictures, Viacom18

Cast: Ayushmann Khurrana, Tabu, Radhika Apte, Anil Dhawan

Rating: 3.5/5

England's lowest Test innings

- 45 v Australia in Sydney, January 28, 1887

- 46 v West Indies in Port of Spain, March 25, 1994

- 51 v West Indies in Kingston, February 4, 2009

- 52 v Australia at The Oval, August 14, 1948

- 53 v Australia at Lord's, July 16, 1888

- 58 v New Zealand in Auckland, March 22, 2018

My Country: A Syrian Memoir

Kassem Eid, Bloomsbury

How much of your income do you need to save?

The more you save, the sooner you can retire. Tuan Phan, a board member of SimplyFI.com, says if you save just 5 per cent of your salary, you can expect to work for another 66 years before you are able to retire without too large a drop in income.

In other words, you will not save enough to retire comfortably. If you save 15 per cent, you can forward to another 43 working years. Up that to 40 per cent of your income, and your remaining working life drops to just 22 years. (see table)

Obviously, this is only a rough guide. How much you save will depend on variables, not least your salary and how much you already have in your pension pot. But it shows what you need to do to achieve financial independence.

How to apply for a drone permit

- Individuals must register on UAE Drone app or website using their UAE Pass

- Add all their personal details, including name, nationality, passport number, Emiratis ID, email and phone number

- Upload the training certificate from a centre accredited by the GCAA

- Submit their request

What are the regulations?

- Fly it within visual line of sight

- Never over populated areas

- Ensure maximum flying height of 400 feet (122 metres) above ground level is not crossed

- Users must avoid flying over restricted areas listed on the UAE Drone app

- Only fly the drone during the day, and never at night

- Should have a live feed of the drone flight

- Drones must weigh 5 kg or less

Under 19 Cricket World Cup, Asia Qualifier

Fixtures

Friday, April 12, Malaysia v UAE

Saturday, April 13, UAE v Nepal

Monday, April 15, UAE v Kuwait

Tuesday, April 16, UAE v Singapore

Thursday, April 18, UAE v Oman

UAE squad

Aryan Lakra (captain), Aaron Benjamin, Akasha Mohammed, Alishan Sharafu, Anand Kumar, Ansh Tandon, Ashwanth Valthapa, Karthik Meiyappan, Mohammed Faraazuddin, Rishab Mukherjee, Niel Lobo, Osama Hassan, Vritya Aravind, Wasi Shah

The Lowdown

Kesari

Rating: 2.5/5 stars

Produced by: Dharma Productions, Azure Entertainment

Directed by: Anubhav Singh

Cast: Akshay Kumar, Parineeti Chopra

Fifa Club World Cup quarter-final

Esperance de Tunis 0

Al Ain 3 (Ahmed 02’, El Shahat 17’, Al Ahbabi 60’)

Dhadak 2

Director: Shazia Iqbal

Starring: Siddhant Chaturvedi, Triptii Dimri

Rating: 1/5

Our legal consultant

Name: Hassan Mohsen Elhais

Position: legal consultant with Al Rowaad Advocates and Legal Consultants.

Some of Darwish's last words

"They see their tomorrows slipping out of their reach. And though it seems to them that everything outside this reality is heaven, yet they do not want to go to that heaven. They stay, because they are afflicted with hope." - Mahmoud Darwish, to attendees of the Palestine Festival of Literature, 2008

His life in brief: Born in a village near Galilee, he lived in exile for most of his life and started writing poetry after high school. He was arrested several times by Israel for what were deemed to be inciteful poems. Most of his work focused on the love and yearning for his homeland, and he was regarded the Palestinian poet of resistance. Over the course of his life, he published more than 30 poetry collections and books of prose, with his work translated into more than 20 languages. Many of his poems were set to music by Arab composers, most significantly Marcel Khalife. Darwish died on August 9, 2008 after undergoing heart surgery in the United States. He was later buried in Ramallah where a shrine was erected in his honour.

Who has lived at The Bishops Avenue?

- George Sainsbury of the supermarket dynasty, sugar magnate William Park Lyle and actress Dame Gracie Fields were residents in the 1930s when the street was only known as ‘Millionaires’ Row’.

- Then came the international super rich, including the last king of Greece, Constantine II, the Sultan of Brunei and Indian steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal who was at one point ranked the third richest person in the world.

- Turkish tycoon Halis Torprak sold his mansion for £50m in 2008 after spending just two days there. The House of Saud sold 10 properties on the road in 2013 for almost £80m.

- Other residents have included Iraqi businessman Nemir Kirdar, singer Ariana Grande, holiday camp impresario Sir Billy Butlin, businessman Asil Nadir, Paul McCartney’s former wife Heather Mills.

Hunting park to luxury living

- Land was originally the Bishop of London's hunting park, hence the name

- The road was laid out in the mid 19th Century, meandering through woodland and farmland

- Its earliest houses at the turn of the 20th Century were substantial detached properties with extensive grounds

Innotech Profile

Date started: 2013

Founder/CEO: Othman Al Mandhari

Based: Muscat, Oman

Sector: Additive manufacturing, 3D printing technologies

Size: 15 full-time employees

Stage: Seed stage and seeking Series A round of financing

Investors: Oman Technology Fund from 2017 to 2019, exited through an agreement with a new investor to secure new funding that it under negotiation right now.

Who's who in Yemen conflict

Houthis: Iran-backed rebels who occupy Sanaa and run unrecognised government

Yemeni government: Exiled government in Aden led by eight-member Presidential Leadership Council

Southern Transitional Council: Faction in Yemeni government that seeks autonomy for the south

Habrish 'rebels': Tribal-backed forces feuding with STC over control of oil in government territory

SPEC SHEET

Display: 10.4-inch IPS LCD, 400 nits, toughened glass

CPU: Unisoc T610; Mali G52 GPU

Memory: 4GB

Storage: 64GB, up to 512GB microSD

Camera: 8MP rear, 5MP front

Connectivity: Wi-Fi, Bluetooth 5.0, USB-C, 3.5mm audio

Battery: 8200mAh, up to 10 hours video

Platform: Android 11

Audio: Stereo speakers, 2 mics

Durability: IP52

Biometrics: Face unlock

Price: Dh849