The skylines of the world's major cities share one abiding characteristic – thickets of commercial and residential towers, most of which have been designed, delivered and marketed using what has become a tick-box adjective: iconic.

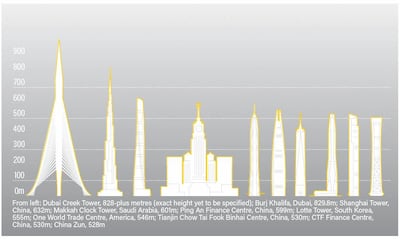

That word does, of course, apply to Burj Khalifa because it’s the first ultra-tall skyscraper and, whether you’re a cynic or a design addict, it triggers a sense of shock and awe.

That visceral, size-based reaction to buildings has a long history. It was experienced by those who first gazed up at the 139-metre-high Great Pyramid of Giza more than 4,000 years ago. About three millennia later, the same feeling was induced by the towers of medieval cathedrals.

In the late 19th century, the unprecedented height of the Eiffel Tower – four times taller than the suddenly stumpy-looking Notre Dame cathedral – would have seemed just as physically stunning as Burj Khalifa does now.

https://players.brightcove.net/5367332862001/6PsTC3MuVq_default/index.html?videoId=6119253999001

Reaching for the skies using modern architectural structures began in 1885 with the Home Insurance Building, which stood at the corner of Adams and LaSalle Streets in Chicago. Designed by William Le Baron Jenney, this was the first tall habitable building constructed with a steel frame, and it loomed above the city centre.

Efficient structural frames, combined with rising land prices in city centres, encouraged property developers and their architects to think up rather than along. And there were at least three other pivotal factors which drove architecture to new heights: Englishman Henry Bessemer's invention of cheaply manufactured decarbonised steel in 1885; the installation of the first safe, reliable elevator – designed by Elisha Otis – at New York's Haughwout department store in 1857; and steam-powered central heating.

Chicago was the birthplace of tall buildings and, by the turn of the 20th century, great American architects such as Louis Sullivan, John Wellborn Root and Daniel Burnham led the world in upwardly mobile buildings such as the Rookery (which still stands in South LaSalle Street) and the equally enduring Masonic Temple, the world's first 21-storey building. At this point, the top of the tops was the 103-metre-tall American Surety Building in New York.

The facades of these buildings had decorative brick skins and looked like pumped-up versions of standard Victorian and Edwardian low-rise architecture. There was no hint that they had modern steel skeletons, or that many of them stood on new-fangled "grillage" foundations; layers of criss-crossed steel beams set into massive, rock-steady slabs of concrete.

Equally impressive proto-skyscrapers appeared elsewhere. The 91-metre Royal Liver Building in Liverpool, England, for example, and the so-called Inkpot building in Utrecht, the Netherlands. But they didn't always inspire praise: some eminent architects refused to design tall buildings (more on this later), and in 1907, US novelist Henry James labelled them "giants of the mere market" and "mercenary monsters".

But the high-rise trend became unstoppable when two mega-structures in New York set the benchmark for modern skyscraper design: the 77-storey Chrysler Building in 1930 and, a year later, the Empire State Building. The Chrysler's shimmering, polished steel Art Deco "crown" introduced an artistic wow factor to this genre of architecture; and the 102-storey Empire State was a paragon of modernist efficiencies – fully designed in two weeks, and erected using prefabricated steel sections that began to rise on March 17. Four months later, half the building's steel structure was in place – a perfect demonstration of the inventive, can-do spirit of the post-war age.

Skyscraper-fever afflicted even the most grounded of the 20th-century’s architectural geniuses. In 1956, Frank Lloyd Wright produced a design for a mile-high, 528-storey tower equipped with five-storey-high, nuclear-powered elevators. Even so, there was something genuinely visionary about Wright’s design: his tower’s slim, subtly sculpted pyramidal form resembles a cross between Burj and the currently on-hold Kingdom Tower in Jeddah.

The mirror-opposite of Wright's extraordinary proposal took shape in 1958 with the first, and perhaps ultimate, example of minimalist tower design – the super-sleek Seagram Building in Manhattan, created by another of architecture's greats, Mies van der Rohe. This building has been copied thousands of times all over the world and features so-called "curtain-wall" facades with alternating bands of dark glass and metal panels, which are hung from the building's reinforced concrete inner structure.

And then, in Chicago between 1969 and 1973, came two huge steps forward in skyscraper design: the 100-storey Hancock tower and the 110-storey Willis tower, formerly the Sears tower, both designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, which also designed Burj Khalifa. The graphic beauty of the Hancock's bronzed steel exoskeleton has never been surpassed; nor has the sheer presence of the darkly rising shoulders of the Willis tower.

The engineer involved was Fazlur Khan, who perfected the "structural tube" concept – an extremely stiff and strong outer structural envelope composed of vertical columns locked together with external beams. He followed that with the even more brilliant "bundled tube" system, used for the Willis tower. The latter remains the most common structural system for higher towers designed in more sculpted shapes, and even at angles. Think of the 18-degree slant of the Capital Gate in Abu Dhabi, the weird, twisting forms of the Evolution Tower in Moscow and the Mode Gakuen Spiral Towers in Nagoya, Japan.

Very different, but equally unexpected, is the 601-metre-high clock tower segment of the Abraj Al-Bait hotel complex in Makkah, of which the grandly retro architecture recalls giant-sized Soviet-era projects in Moscow, such as the Hotel Ukrayina and the unbuilt Palace of the Soviets, designed in 1939.

Tower design virtuosity continues to be a default approach by urban developers, even if it is disliked by some of architecture's most eminent figures. Danish urban design guru Jan Gehl dismisses skyscrapers, saying: "The starchitects fly in, fly out, and drop some buildings here and there, with no [regard to] context."

His scything criticism divides even the most intellectual of designers. Architect, professor and architectural theorist Rem Koolhaas agrees that really big buildings rupture their urban settings. Yet the equally cerebral French architect Jean Nouvel is perfectly happy to say of one tower he designed that it has "assumed its full virility".

That remark would horrify the Victorian-cum-Edwardian ghosts of William Le Baron Jenney and Louis Sullivan, but you can bet they were hovering over Manhattan to witness the continuous 18-hour, 400-truckload concrete pour for the vast foundation slab of the One Vanderbilt tower in 2017. They would be equally mesmerised to gaze down on the rising structure of the ultra-skinny Steinway Tower, whose 82 storeys are only 18 metres wide.

They're probably shadowing the construction of the forthcoming Dubai Creek Tower, too. Designed by Santiago Calatrava, this is an extremely slender, stem-like tower crowned with a bud-like observation section that will be more than the height of Burj Khalifa. Plus, the wow factor here is something else – a towering "skirt" of criss-crossed, tensioned steel cables that will hold the tower up. One can almost hear Calatrava murmuring: "Look! No hands!"