Renewed social unrest in Tunisia could hamper the government's attempts to put its economy on a stronger footing following the damage caused by Covid-19 and could delay its negotiations with the International Monetary Fund for a much-needed debt restructuring.

"Without a government in place, there is no momentum to push through much-needed and unpopular fiscal consolidation to address Tunisia’s fragile public finances," said James Swanston, an economist covering the Middle East and North Africa for London-based Capital Economics.

"Admittedly, if after 30 days President [Kais] Saied has formed a new government, it could pave the way to unblock the political impasse ... but this seems quite unlikely."

Mr Saied sacked the country's prime minister Hichem Mechichi on Sunday and froze parliamentary activity for a month, bringing to a head a political crisis that has been dragging on for two years – a move that could derail its economic reforms.

An uprising in the country more than a decade ago toppled its longtime dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and plunged the country into economic chaos.

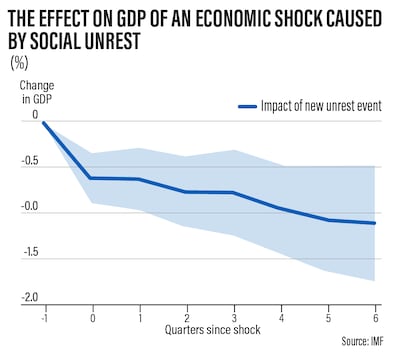

The Reported Social Unrest Index, a measure developed by IMF staff, found that disturbances within a country can shave between 0.2 per cent to 1 per cent off a country's gross domestic product, depending on their severity.

Economic growth can also remain lower than pre-disturbance levels for up to 18 months after a major protest, according to the fund.

"These effects on GDP seem to be driven by sharp contractions in manufacturing and services and consumption. Our findings also suggest that social unrest affects activity by lowering confidence and increasing uncertainty," a blog published by the multilateral lender earlier this month found.

Tunisia's economy had already been in a weakened state before Covid-19, with its fiscal deficit averaging 5 per cent of GDP in the decade ending in 2019, according to Capital Economics.

The budget gap increased to 10.6 per cent of GDP last year as 2.6 billion dinars ($946m) was pumped in to support its economy and is forecast to hit 9.3 per cent this year, according to the fund.

Tunisia's government requested help from the Washington lender in May for a support programme that would alleviate the country's plight. The programme was reported to involve reforms including cuts to the public sector wage bill but faced stiff opposition from the country's main labour union.

Government debt has increased sharply to about 90 per cent of GDP, driven by the country's high public sector wage bill, generous subsidies and support for weak state-owned enterprises, Mr Swanston said.

About two thirds of this is owed to external borrowers and denominated in foreign currency, leaving the country vulnerable to a fall in the value of the dinar.

The dinar was trading at its lowest for more than a year at 2.8074 against the US dollar at 2.50pm on Monday.

"Much-needed fiscal consolidation measures are needed but against the backdrop of the political crisis and a weak economic recovery, it will prove very difficult to push through," said Mr Swanston.

"Ultimately, we think the government will be forced to restructure its debts."

The End of Loneliness

Benedict Wells

Translated from the German by Charlotte Collins

Sceptre

French business

France has organised a delegation of leading businesses to travel to Syria. The group was led by French shipping giant CMA CGM, which struck a 30-year contract in May with the Syrian government to develop and run Latakia port. Also present were water and waste management company Suez, defence multinational Thales, and Ellipse Group, which is currently looking into rehabilitating Syrian hospitals.

Company%C2%A0profile

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3Eamana%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2010%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Karim%20Farra%20and%20Ziad%20Aboujeb%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EUAE%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERegulator%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDFSA%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFinancial%20services%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ECurrent%20number%20of%20staff%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E85%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestment%20stage%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESelf-funded%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Mercer, the investment consulting arm of US services company Marsh & McLennan, expects its wealth division to at least double its assets under management (AUM) in the Middle East as wealth in the region continues to grow despite economic headwinds, a company official said.

Mercer Wealth, which globally has $160 billion in AUM, plans to boost its AUM in the region to $2-$3bn in the next 2-3 years from the present $1bn, said Yasir AbuShaban, a Dubai-based principal with Mercer Wealth.

“Within the next two to three years, we are looking at reaching $2 to $3 billion as a conservative estimate and we do see an opportunity to do so,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Mercer does not directly make investments, but allocates clients’ money they have discretion to, to professional asset managers. They also provide advice to clients.

“We have buying power. We can negotiate on their (client’s) behalf with asset managers to provide them lower fees than they otherwise would have to get on their own,” he added.

Mercer Wealth’s clients include sovereign wealth funds, family offices, and insurance companies among others.

From its office in Dubai, Mercer also looks after Africa, India and Turkey, where they also see opportunity for growth.

Wealth creation in Middle East and Africa (MEA) grew 8.5 per cent to $8.1 trillion last year from $7.5tn in 2015, higher than last year’s global average of 6 per cent and the second-highest growth in a region after Asia-Pacific which grew 9.9 per cent, according to consultancy Boston Consulting Group (BCG). In the region, where wealth grew just 1.9 per cent in 2015 compared with 2014, a pickup in oil prices has helped in wealth generation.

BCG is forecasting MEA wealth will rise to $12tn by 2021, growing at an annual average of 8 per cent.

Drivers of wealth generation in the region will be split evenly between new wealth creation and growth of performance of existing assets, according to BCG.

Another general trend in the region is clients’ looking for a comprehensive approach to investing, according to Mr AbuShaban.

“Institutional investors or some of the families are seeing a slowdown in the available capital they have to invest and in that sense they are looking at optimizing the way they manage their portfolios and making sure they are not investing haphazardly and different parts of their investment are working together,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Some clients also have a higher appetite for risk, given the low interest-rate environment that does not provide enough yield for some institutional investors. These clients are keen to invest in illiquid assets, such as private equity and infrastructure.

“What we have seen is a desire for higher returns in what has been a low-return environment specifically in various fixed income or bonds,” he said.

“In this environment, we have seen a de facto increase in the risk that clients are taking in things like illiquid investments, private equity investments, infrastructure and private debt, those kind of investments were higher illiquidity results in incrementally higher returns.”

The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, one of the largest sovereign wealth funds, said in its 2016 report that has gradually increased its exposure in direct private equity and private credit transactions, mainly in Asian markets and especially in China and India. The authority’s private equity department focused on structured equities owing to “their defensive characteristics.”

Sukuk explained

Sukuk are Sharia-compliant financial certificates issued by governments, corporates and other entities. While as an asset class they resemble conventional bonds, there are some significant differences. As interest is prohibited under Sharia, sukuk must contain an underlying transaction, for example a leaseback agreement, and the income that is paid to investors is generated by the underlying asset. Investors must also be prepared to share in both the profits and losses of an enterprise. Nevertheless, sukuk are similar to conventional bonds in that they provide regular payments, and are considered less risky than equities. Most investors would not buy sukuk directly due to high minimum subscriptions, but invest via funds.

Tips on buying property during a pandemic

Islay Robinson, group chief executive of mortgage broker Enness Global, offers his advice on buying property in today's market.

While many have been quick to call a market collapse, this simply isn’t what we’re seeing on the ground. Many pockets of the global property market, including London and the UAE, continue to be compelling locations to invest in real estate.

While an air of uncertainty remains, the outlook is far better than anyone could have predicted. However, it is still important to consider the wider threat posed by Covid-19 when buying bricks and mortar.

Anything with outside space, gardens and private entrances is a must and these property features will see your investment keep its value should the pandemic drag on. In contrast, flats and particularly high-rise developments are falling in popularity and investors should avoid them at all costs.

Attractive investment property can be hard to find amid strong demand and heightened buyer activity. When you do find one, be prepared to move hard and fast to secure it. If you have your finances in order, this shouldn’t be an issue.

Lenders continue to lend and rates remain at an all-time low, so utilise this. There is no point in tying up cash when you can keep this liquidity to maximise other opportunities.

Keep your head and, as always when investing, take the long-term view. External factors such as coronavirus or Brexit will present challenges in the short-term, but the long-term outlook remains strong.

Finally, keep an eye on your currency. Whenever currency fluctuations favour foreign buyers, you can bet that demand will increase, as they act to secure what is essentially a discounted property.

More from Rashmee Roshan Lall

LILO & STITCH

Starring: Sydney Elizebeth Agudong, Maia Kealoha, Chris Sanders

Director: Dean Fleischer Camp

Rating: 4.5/5

COMPANY PROFILE

Name: Cofe

Year started: 2018

Based: UAE

Employees: 80-100

Amount raised: $13m

Investors: KISP ventures, Cedar Mundi, Towell Holding International, Takamul Capital, Dividend Gate Capital, Nizar AlNusif Sons Holding, Arab Investment Company and Al Imtiaz Investment Group

Engine: 5.6-litre V8

Transmission: seven-speed automatic

Power: 400hp

Torque: 560Nm

Price: Dh234,000 - Dh329,000

On sale: now

A State of Passion

Directors: Carol Mansour and Muna Khalidi

Stars: Dr Ghassan Abu-Sittah

Rating: 4/5

'Brazen'

Director: Monika Mitchell

Starring: Alyssa Milano, Sam Page, Colleen Wheeler

Rating: 3/5

Vidaamuyarchi

Director: Magizh Thirumeni

Stars: Ajith Kumar, Arjun Sarja, Trisha Krishnan, Regina Cassandra

Rating: 4/5

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

Our family matters legal consultant

Name: Hassan Mohsen Elhais

Position: legal consultant with Al Rowaad Advocates and Legal Consultants.

TOUR RESULTS AND FIXTURES

June 3: NZ Provincial Barbarians 7 Lions 13

June 7: Blues 22 Lions 16

June 10: Crusaders 3 Lions 12

June 13: Highlanders 23 Lions 22

June 17: Maori All Blacks 10 Lions 32

June 20: Chiefs 6 Lions 34

June 24: New Zealand 30 Lions 15 (First Test)

June 27: Hurricanes 31 Lions 31

July 1: New Zealand 21 Lions 24 (Second Test)

July 8: New Zealand v Lions (Third Test) - kick-off 11.30am (UAE)

Sholto Byrnes on Myanmar politics

Tamkeen's offering

- Option 1: 70% in year 1, 50% in year 2, 30% in year 3

- Option 2: 50% across three years

- Option 3: 30% across five years

LOVE%20AGAIN

%3Cp%3EDirector%3A%20Jim%20Strouse%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EStars%3A%20Priyanka%20Chopra%20Jonas%2C%20Sam%20Heughan%2C%20Celine%20Dion%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ERating%3A%202%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

F1 The Movie

Starring: Brad Pitt, Damson Idris, Kerry Condon, Javier Bardem

Director: Joseph Kosinski

Rating: 4/5

In Full Flight: A Story of Africa and Atonement

John Heminway, Knopff