The St Regis Bahia Beach Resort in Puerto Rico has a golf course and oceanfront residences in a 195-hectare nature reserve, set along azure waters and lush rainforest. But what is perhaps most appealing to those who are now rushing to this property is the section on its website explaining tax benefits for island residents.

That was the case for Anthony Emtman, who left Los Angeles behind and bought an apartment at the resort in March. The chief executive of Ikigai Asset Management is now a part of a burgeoning cryptocurrency community along Puerto Rico’s north shore, where the tropical weather is a bonus.

Mr Emtman and his cryptocurrency peers are taking a page out of hedge funds’ books and seeking residence on the island to reap huge tax savings.

High-earning investors in the US pay up to 20 per cent in capital gains tax and as much as 37 per cent on short-term gains. In Puerto Rico, they pay nothing.

Companies based on the American mainland pay 21 per cent in federal corporate tax plus an individual state tax, compared with only 4 per cent on the island. That makes the move a no-brainer for some investors, especially as the cryptocurrency market’s spectacular growth continues and Democrats push for higher taxes on the rich.

The presence of digital currency enthusiasts is already palpable on the small island, where chance encounters and networking opportunities abound: run-ins at taco stands, dinner at luxury apartments and “Crypto Monday” gatherings at hotels and restaurants across San Juan.

Cryptocurrency funds Pantera Capital and Redwood City Ventures are among those that have established offices on the island. Facebook product manager-turned-whistle-blower Frances Haugen recently told The New York Times she is living in Puerto Rico in part to be with her “crypto friends”.

New York City’s mayor-elect Eric Adams even flew there in November with cryptocurrency billionaire Brock Pierce for dinner with Puerto Rico’s governor Pedro Pierluisi.

Now, “it is not just, ‘Move to Puerto Rico to save tax’,” says Giovanni Mendez, a corporate and tax lawyer advising those who relocate. “It is ‘Move to Puerto Rico because everybody is there’.”

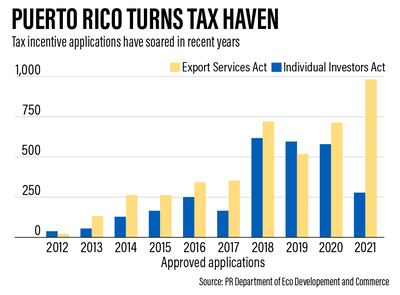

The Puerto Rican government created the tax breaks in 2012 with the hope of infusing the island’s struggling economy with cash and diversifying its job pool.

Hedge funds gradually began seeking a toehold on the island but what has really supercharged the flurry of arrivals is the Covid-19 pandemic – which drove a shift away from big cities and popularised remote work – and the recent explosion in cryptocurrency markets.

Proponents of the tax breaks describe it as not only a boost for an island that has been mired in bankruptcy for more than four years – prolonged by hurricanes, earthquakes, a political scandal and the pandemic – but an opportunity for reinvention.

Still, the idea has its detractors: some of the laws only apply to new residents, so lifelong islanders are ineligible. It has made some hesitant to welcome the new crop of wealthy denizens, fearful that the flow of income will exacerbate inequality and create social tension. As it is, property prices are already rising to “absurd” levels.

During the last big cryptocurrency bull run in 2017, many investors tried to move to Puerto Rico before the market peaked and then collapsed, says Mr Mendez.

This year, Puerto Rico has received more than 1,200 applications – a record – through its Individual Investors Act, which exempts new residents from paying taxes on capital gains, according to the island’s Department of Economic Development and Commerce. The number of US mainlanders seeking Puerto Rico’s tax breaks has tripled this year.

Another 274 corporations, limited liability companies, partnerships and other entities were approved for the Exports Services Act, which provides a 4 per cent corporate tax rate and a 100 per cent exemption on dividends.

Both fall under Puerto Rico’s Act 60, a group of tax breaks that were packaged together in 2019 to attract investment not only from cryptocurrency, but finance, technology and other industries.

The cryptocurrency crowd has primarily gravitated to three areas along the coast.

corporate and tax lawyer

There are the secluded escapes, like Bahia and the Ritz-Carlton-branded Dorado Beach resort. Those seeking a more urban lifestyle have opted for Condado, a high-end neighbourhood and shopping district in San Juan.

“There are restaurants and there are coffee shops and there is a mall,” says Brent Johnson, the chief executive of wealth management company Santiago Capital, who moved from San Francisco to Condado in May. “It is kind of like a mini Miami.”

During his time in Puerto Rico, Mr Johnson has been able to connect with wealth management, private equity and cryptocurrency companies, as well as people in the property, pharmaceutical, energy and agricultural sectors.

“I felt like I could come here, do my job, and still be plugged into the financial community, much more so than going to somewhere like Hawaii or Mexico,” he says.

Property boom

The influx of newcomers is causing waves in the property market, particularly in the resort communities.

Dorado has had the most growth, with prices almost tripling, according to Priscilla Ferrer, a Puerto Rican broker.

“It is absurd,” she says. “These luxury properties are getting bought for an emotional rate and not an economic rate.”

Francisco Fournier, founding partner of Luxury Collection Real Estate, says it is now common to see properties sell for more than $20 million.

“Right now, we are selling a home in Dorado Beach for $27m and another one is going for $29m,” he says.

In Bahia, prices per square foot have almost doubled, according to Blanca Lopez, founder of Gramercy Real Estate Group.

real estate broker, Puerto Rico

“We are seeing prices north of $3,000 per square foot,” she says, while high-end home values in Condado are around $1,400 to $1,500 per square foot, a roughly 35 per cent increase from a year ago.

And there is not enough inventory to satiate demand as buyers are flocking to the island faster than high-end homes can be built.

As wealthier people gain ground elsewhere, it hurts housing and job prospects for islanders, says Raul Santiago-Bartolomei, an assistant professor at the University of Puerto Rico’s Graduate School of Planning.

“It is making these places more unattainable for a workforce and low-income households that actually need to be living near these high opportunity areas,” he says.

There are several new residential towers rising in Condado but that will not be enough to keep pace. There is even a labour shortage, Mr Fournier says, so Puerto Rico is working with the US Department of State to secure visas to bring “people from the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Haiti and South America because we don’t have the people to build”.

So far, the incentives appear to be creating jobs.

From 2015 to 2019, the Individual Investors Act added about 4,400 jobs and the Export Services Act added 36,222, according to a study by Puerto Rican consulting company Estudios Tecnicos. Call centres accounted for most of the jobs, followed by consulting services, advertising, public relations and tax and accounting services.

As long as the jobs are coming, the “doors are open” for the cryptocurrency community, says Carlos Fontan, director of incentives at the Department of Economic Development and Commerce.

The tax breaks are doing what they were intended to, says Alberto Baco-Bague, the department’s former secretary and a driving force behind Act 60.

“Ideally, we want to be building one Puerto Rico,” he says. “Not one Puerto Rico for new residents and another one for local business leaders.”

assistant professor at the University of Puerto Rico

Still, one of the biggest challenges is convincing the local population of the programme’s economic benefits.

The Individual Investors Act, also known as Act 22, only applies to non-Puerto Ricans, meaning islanders are ineligible. And even though the Export Services Act is available to locals, many assume otherwise because the tax break is often marketed alongside programmes for foreigners.

Puerto Rico is not the first to try to attract cryptocurrency investment, and it certainly will not be the last.

The economy of El Zonte, a surf town on El Salvador’s Pacific coast, runs on Bitcoin. El Salvador’s president Nayib Bukele was a proponent of cryptocurrency long before taking office in 2019.

This year, the country adopted Bitcoin as its national currency, and announced plans for the first sovereign Bitcoin bonds and a tax-free Bitcoin City.

Portugal, too, is not axing the buying or selling of cryptocurrencies, unless it is an individual’s main source of income.