The Antarctic is losing ice and growing plants at a rapid rate due to climate change, scientists say, raising serious concerns about the environmental future of the peninsula.

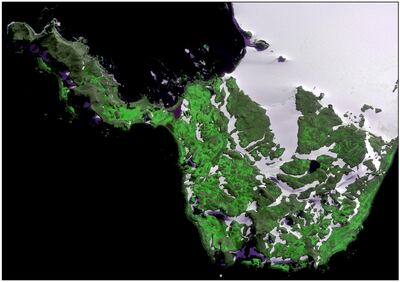

The continent, described as the world’s coldest, highest, driest and windiest, has seen its area of vegetation cover grow tenfold in recent decades, from less than one square kilometre in 1986 to almost 12 square kilometres by 2021, according to a study that used satellite imagery to build a picture of how the Antarctic has changed. The trend has accelerated by almost a third since 2016, expanding by more than 400,000 square metres each year in the period.

Dr Dominic Hodgson, interim director of science at British Antarctic Survey, which conducted the research alongside the universities of Exeter and Hertfordshire, told The National the increase varies in different parts of the Antarctic Peninsula, but it is particularly focused on areas "where there is enough water or nutrient availability for plants to become established and extend their range".

"For example, at Robert Island, there has been a nearly 20 per cent increase in vegetated area from 2013 and 2016," he said. "The problem is that human-driven warming of the planet is particularly felt in the polar regions. This allows existing Antarctic plants to expand their range - but more worryingly, it creates an environment where non-indigenous species can become established. These non-indigenous species can disrupt delicate Antarctic biological systems."

Dr Thomas Roland from the University of Exeter said the landscape is still almost entirely dominated by snow, ice and rock, with only a tiny fraction colonised by plant life. “But that tiny fraction has grown dramatically – showing that even this vast and isolated ‘wilderness’ is being affected by anthropogenic climate change," he added.

The Antarctic Peninsula, like many polar regions, is warming faster than the global average, registering more frequent heatwaves, like in 2022, when temperatures reached an all-time high of -9.4°C, some 30°C – 40°C above average in March of that year, a typically transitional month into Antarctic winter at Concordia Station.

This warming means greening is likely to increase in the future, said Dr Olly Bartlett, from the University of Hertfordshire. “Soil in Antarctica is mostly poor or non-existent, but this increase in plant life will add organic matter, and facilitate soil formation – potentially paving the way for other plants to grow,” he said. “This raises the risk of non-native and invasive species arriving, possibly carried by eco-tourists, scientists or other visitors to the continent.”

The researchers said further research is urgently needed to establish the specific climate and environmental factors driving the “greening” trend.

“The sensitivity of the Antarctic Peninsula’s vegetation to climate change is now clear and, under future anthropogenic warming, we could see fundamental changes to the biology and landscape of this iconic and vulnerable region,” said Dr Roland. “Our findings raise serious concerns about the environmental future of the Antarctic Peninsula, and of the continent as a whole. In order to protect Antarctica, we must understand these changes and identify precisely what is causing them.”

The researchers are now investigating how newly ice-free areas are colonised by plants, and how the process might proceed into the future. The paper, titled Satellites evidence sustained greening of the Antarctic Peninsula, appeared in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Research released last month found that the melting of Antarctica's vast Thwaites Glacier, nicknamed the Doomsday Glacier, will increase “inexorably” this century.

Thwaites, which is roughly the size of Britain and more than 2km thick in places, represents more than half a metre of global sea level rise potential and could destabilise neighbouring glaciers that have the potential to cause a further three-metre rise.

The world’s widest glacier is currently losing about 50 billion more tonnes of ice than it receives in snowfall, in an accelerating process first observed in the 1970s.