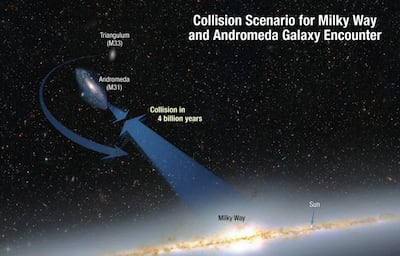

Our solar system is expected to face a dramatic transformation because of an impending galactic event that will see a neighbouring galaxy collide with the Milky Way, potentially throwing planets into interplanetary space.

Life on Earth, however, will likely come to an end billions of years before that as the Sun, our life-giving star, becomes too hot for any living organism to survive.

Humans still have plenty of time, though, as these apocalyptic events are projected to unfold over the next five billion years.

Pauline Barmby, chairwoman of the department of physics and astronomy at the Western University in Ontario, Canada, has described what could be left of our solar system once the Andromeda galaxy eventually merges with it.

“A collision between the Milky Way and Andromeda, if it happens, won’t occur all at once,” she told The National.

“Most models of the galaxies’ orbits have them coming in for a close approach some time between five and eight billion years from now, separating for a few billion years, and then finally coalescing.”

The detailed fate of the solar system is not known with certainty, however, because the current orbits of the galaxies are difficult to measure precisely, according to Ms Barmby.

She said the part of the solar system that would most likely be affected by the Milky Way-Andromeda collision would be the Oort Cloud – a distant region of icy objects and comets surrounding the outer edges of the solar system.

“While nearby stars aren’t likely to themselves collide due to the galaxy collision, their orbits will change, and some will likely come near enough that they gravitationally perturb the Oort Cloud’s comets and eject some of them from the solar system,” said Ms Barmby.

Galaxy mergers can take place over hundreds of millions of years as gravitational forces slowly draw them together, distorting their shape and causing star formation, with the full merger process completing over an extended period.

The Sun holds the key

However, it is the dying Sun that could do the most damage to Earth and its neighbouring planets years before the merger.

It is expected to expand into a red giant mass – when it runs out of hydrogen fuel and swells to many times its original size – destroying Mercury and Venus in the process.

“Mars and the other outer planets are expected to survive, although their orbits will expand,” said Ms Barmby.

“Earth’s fate is unclear, because it’s difficult to predict exactly how much mass the Sun will lose in its red giant phase. If Earth is not destroyed, it certainly won’t be habitable.”

The remaining planets might not last much longer either, as they could be thrown out of the solar system entirely after the galaxy collision, when stars passing near the Sun cause gravitational influences between them.

"Over the very long term, 10 to 100 billion years from now, gravitational perturbations from stars passing near the Sun will cause gravitational interactions between the remaining planets - eventually they too will likely be ejected from the solar system," said Ms Barmby.

Dr Nidhal Guessoum, professor of physics and astronomy at the American University of Sharjah, echoed Ms Barmby’s thoughts and said that life on Earth “will have disappeared” well before the merger.

“As the Sun’s power continues to slowly increase it would make life on Earth impossible in about half a billion years from now,” he said.

While it may be a while until our galaxy merges with another, collisions in the universe are quite common, according to Dr Guessoum.

“We have a number of well-known and well-imaged cases of merged, distorted galaxies," she said. “Such mergers, which are due to gravitational pulls between galaxies, often lead to new stars being formed - and most likely new planets around them - by compression of galactic gas and dust.”

Some of the most well-documented galaxy mergers in the universe include the Antennae Galaxies, labelled as NGC 4038/NGC 4039), where two spiral galaxies are merging, creating tidal tails of stars and intense star formation known as a ‘starburst’.

Another example is the Cartwheel Galaxy, formed when a smaller galaxy passes through a larger one, producing a ring structure and triggering waves of star formation.

City's slump

L - Juventus, 2-0

D - C Palace, 2-2

W - N Forest, 3-0

L - Liverpool, 2-0

D - Feyenoord, 3-3

L - Tottenham, 4-0

L - Brighton, 2-1

L - Sporting, 4-1

L - Bournemouth, 2-1

L - Tottenham, 2-1

Key recommendations

- Fewer criminals put behind bars and more to serve sentences in the community, with short sentences scrapped and many inmates released earlier.

- Greater use of curfews and exclusion zones to deliver tougher supervision than ever on criminals.

- Explore wider powers for judges to punish offenders by blocking them from attending football matches, banning them from driving or travelling abroad through an expansion of ‘ancillary orders’.

- More Intensive Supervision Courts to tackle the root causes of crime such as alcohol and drug abuse – forcing repeat offenders to take part in tough treatment programmes or face prison.

Essentials

The flights

Return flights from Dubai to Windhoek, with a combination of Emirates and Air Namibia, cost from US$790 (Dh2,902) via Johannesburg.

The trip

A 10-day self-drive in Namibia staying at a combination of the safari camps mentioned – Okonjima AfriCat, Little Kulala, Desert Rhino/Damaraland, Ongava – costs from $7,000 (Dh25,711) per person, including car hire (Toyota 4x4 or similar), but excluding international flights, with The Luxury Safari Company.

When to go

The cooler winter months, from June to September, are best, especially for game viewing.

LAST 16

SEEDS

Liverpool, Manchester City, Barcelona, Paris St-Germain, Bayern Munich, RB Leipzig, Valencia, Juventus

PLUS

Real Madrid, Tottenham, Atalanta, Atletico Madrid, Napoli, Borussia Dortmund, Lyon, Chelsea

Notable cricketers and political careers

- India: Kirti Azad, Navjot Sidhu and Gautam Gambhir (rumoured)

- Pakistan: Imran Khan and Shahid Afridi (rumoured)

- Sri Lanka: Arjuna Ranatunga, Sanath Jayasuriya, Tillakaratne Dilshan (rumoured)

- Bangladesh (Mashrafe Mortaza)

What is a black hole?

1. Black holes are objects whose gravity is so strong not even light can escape their pull

2. They can be created when massive stars collapse under their own weight

3. Large black holes can also be formed when smaller ones collide and merge

4. The biggest black holes lurk at the centre of many galaxies, including our own

5. Astronomers believe that when the universe was very young, black holes affected how galaxies formed

Know your Camel lingo

The bairaq is a competition for the best herd of 50 camels, named for the banner its winner takes home

Namoos - a word of congratulations reserved for falconry competitions, camel races and camel pageants. It best translates as 'the pride of victory' - and for competitors, it is priceless

Asayel camels - sleek, short-haired hound-like racers

Majahim - chocolate-brown camels that can grow to weigh two tonnes. They were only valued for milk until camel pageantry took off in the 1990s

Millions Street - the thoroughfare where camels are led and where white 4x4s throng throughout the festival

Is it worth it? We put cheesecake frap to the test.

The verdict from the nutritionists is damning. But does a cheesecake frappuccino taste good enough to merit the indulgence?

My advice is to only go there if you have unusually sweet tooth. I like my puddings, but this was a bit much even for me. The first hit is a winner, but it's downhill, slowly, from there. Each sip is a little less satisfying than the last, and maybe it was just all that sugar, but it isn't long before the rush is replaced by a creeping remorse. And half of the thing is still left.

The caramel version is far superior to the blueberry, too. If someone put a full caramel cheesecake through a liquidiser and scooped out the contents, it would probably taste something like this. Blueberry, on the other hand, has more of an artificial taste. It's like someone has tried to invent this drink in a lab, and while early results were promising, they're still in the testing phase. It isn't terrible, but something isn't quite right either.

So if you want an experience, go for a small, and opt for the caramel. But if you want a cheesecake, it's probably more satisfying, and not quite as unhealthy, to just order the real thing.

'Worse than a prison sentence'

Marie Byrne, a counsellor who volunteers at the UAE government's mental health crisis helpline, said the ordeal the crew had been through would take time to overcome.

“It was worse than a prison sentence, where at least someone can deal with a set amount of time incarcerated," she said.

“They were living in perpetual mystery as to how their futures would pan out, and what that would be.

“Because of coronavirus, the world is very different now to the one they left, that will also have an impact.

“It will not fully register until they are on dry land. Some have not seen their young children grow up while others will have to rebuild relationships.

“It will be a challenge mentally, and to find other work to support their families as they have been out of circulation for so long. Hopefully they will get the care they need when they get home.”

Who's who in Yemen conflict

Houthis: Iran-backed rebels who occupy Sanaa and run unrecognised government

Yemeni government: Exiled government in Aden led by eight-member Presidential Leadership Council

Southern Transitional Council: Faction in Yemeni government that seeks autonomy for the south

Habrish 'rebels': Tribal-backed forces feuding with STC over control of oil in government territory

MATCH INFO

Tottenham 4 (Alli 51', Kane 50', 77'. Aurier 73')

Olympiakos 2 (El-Arabi 06', Semedo')

VERSTAPPEN'S FIRSTS

Youngest F1 driver (17 years 3 days Japan 2014)

Youngest driver to start an F1 race (17 years 166 days – Australia 2015)

Youngest F1 driver to score points (17 years 180 days - Malaysia 2015)

Youngest driver to lead an F1 race (18 years 228 days – Spain 2016)

Youngest driver to set an F1 fastest lap (19 years 44 days – Brazil 2016)

Youngest on F1 podium finish (18 years 228 days – Spain 2016)

Youngest F1 winner (18 years 228 days – Spain 2016)

Youngest multiple F1 race winner (Mexico 2017/18)

Youngest F1 driver to win the same race (Mexico 2017/18)

ESSENTIALS

The flights

Emirates flies direct from Dubai to Rio de Janeiro from Dh7,000 return including taxes. Avianca fliles from Rio to Cusco via Lima from $399 (Dhxx) return including taxes.

The trip

From US$1,830 per deluxe cabin, twin share, for the one-night Spirit of the Water itinerary and US$4,630 per deluxe cabin for the Peruvian Highlands itinerary, inclusive of meals, and beverages. Surcharges apply for some excursions.

Essentials

The flights

Emirates, Etihad and Malaysia Airlines all fly direct from the UAE to Kuala Lumpur and on to Penang from about Dh2,300 return, including taxes.

Where to stay

In Kuala Lumpur, Element is a recently opened, futuristic hotel high up in a Norman Foster-designed skyscraper. Rooms cost from Dh400 per night, including taxes. Hotel Stripes, also in KL, is a great value design hotel, with an infinity rooftop pool. Rooms cost from Dh310, including taxes.

In Penang, Ren i Tang is a boutique b&b in what was once an ancient Chinese Medicine Hall in the centre of Little India. Rooms cost from Dh220, including taxes.

23 Love Lane in Penang is a luxury boutique heritage hotel in a converted mansion, with private tropical gardens. Rooms cost from Dh400, including taxes.

In Langkawi, Temple Tree is a unique architectural villa hotel consisting of antique houses from all across Malaysia. Rooms cost from Dh350, including taxes.

The story of Edge

Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, established Edge in 2019.

It brought together 25 state-owned and independent companies specialising in weapons systems, cyber protection and electronic warfare.

Edge has an annual revenue of $5 billion and employs more than 12,000 people.

Some of the companies include Nimr, a maker of armoured vehicles, Caracal, which manufactures guns and ammunitions company, Lahab

Premier League results

Saturday

Tottenham Hotspur 1 Arsenal 1

Bournemouth 0 Manchester City 1

Brighton & Hove Albion 1 Huddersfield Town 0

Burnley 1 Crystal Palace 3

Manchester United 3 Southampton 2

Wolverhampton Wanderers 2 Cardiff City 0

West Ham United 2 Newcastle United 0

Sunday

Watford 2 Leicester City 1

Fulham 1 Chelsea 2

Everton 0 Liverpool 0

INDIA%20SQUAD

%3Cp%3ERohit%20Sharma%20(capt)%2C%20Shubman%20Gill%2C%20Cheteshwar%20Pujara%2C%20Virat%20Kohli%2C%20Ajinkya%20Rahane%2C%20KL%20Rahul%2C%20KS%20Bharat%20(wk)%2C%20Ravichandran%20Ashwin%2C%20Ravindra%20Jadeja%2C%20Axar%20Patel%2C%20Shardul%20Thakur%2C%20Mohammed%20Shami%2C%20Mohammed%20Siraj%2C%20Umesh%20Yadav%2C%20Jaydev%20Unadkat%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Infiniti QX80 specs

Engine: twin-turbocharged 3.5-liter V6

Power: 450hp

Torque: 700Nm

Price: From Dh450,000, Autograph model from Dh510,000

Available: Now

UAE central contracts

Full time contracts

Rohan Mustafa, Ahmed Raza, Mohammed Usman, Chirag Suri, Mohammed Boota, Sultan Ahmed, Zahoor Khan, Junaid Siddique, Waheed Ahmed, Zawar Farid

Part time contracts

Aryan Lakra, Ansh Tandon, Karthik Meiyappan, Rahul Bhatia, Alishan Sharafu, CP Rizwaan, Basil Hameed, Matiullah, Fahad Nawaz, Sanchit Sharma