Diamonds hold a special place in our collective imagination. They have been gifted as love tokens, taken as the spoils of war and utilised as emblems of power, embedded into thrones, crowns and sceptres. And of all diamonds, it is the Koh-i-Noor that is arguably the most intriguing. One of the largest and most impressive diamonds ever mined, the Koh-i-Noor originated in ancient India, was gifted by Maharaja Ranjit Singh to Queen Victoria in 1849, and now forms part of the British Crown Jewels.

Except that isn't entirely true.

What we think we know of the Koh-i-Noor has recently been revealed to be little more than embellished gossip, lifted from the bazaars of Lahore and retold as fact by one Theo Metcalfe, who in the 1850s was tasked with tracing the origins of the stone. Unable to find anything of substance, it seems the enterprising Mr Metcalfe simply made it up, creating a muddled and chaotic history that survives to this day. Add to that the fact that while the diamond now resides in the United Kingdom, four other nations lay claim to it, with India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran and even the Taliban all calling for it to be returned to them and, therefore, its rightful home.

Presumably frustrated that something so famous could be so little understood, authors William Dalrymple and Anita Anand decided to join forces to uncover the truth about the gem, penning a biography entitled Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond. "We both had the Koh-i Noor glittering at the back of our previous books," Dalrymple explains via telephone from his home in India. "It had wound its way into both our writing lives. I had written a book about Afghanistan called Return of a King, where Shuja ul-Mulk loses the diamond to Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Anita came across it when she was writing about the story of Sophia Duleep Singh, the daughter of Duleep Singh, who was the last Indian to possess the stone," he explains.

Already familiar – at least in part – with its story, the duo was astonished to hear the attorney general of India declare that the diamond had been gifted to the British by Ranjit Singh in 1849. Knowing full well that the maharaja had died a decade earlier, and in fact it was his son, Duleep, who had handed the gem over, the pair realised they were in a position to tell the true story of the most famous gem in the world.

"For a writer, every time you discover some fantastic story that is different from the authorised version, you give a little whoop," Dalrymple says. "So that's when we got together and decided to write this."

The story they uncovered is an astonishing Game of Thrones-esque yarn of intrigue, betrayal and brutality. In its wake, the Koh-i-Noor has left a trail of destruction and savagery, with more than a few men (and even women) meeting unpleasant ends – such as being blinded with needles, crushed by masonry, strangled, stabbed, beaten with bricks and even murdered with molten gold – because of their association with the gem. We might like to view our jewels as benign and pretty, but the Koh-i-Noor is anything but. "It is very far from romantic," laughs Dalrymple, "and has left this incredible trail of blood and suffering wherever it has gone. The interesting thing is seeing how diamonds are viewed in different cultures and at different times. The idea that a diamond is something that you give on an engagement ring is very much of the late 19th-century and a European invention. Before that, they meant very different things to different people," he explains.

Before Dalrymple and Anand's book, the established story of this gem suggested that it was extracted from the great mines of Kollur, and first appeared as the Syamantaka diamond, in the 5,000-year-old Hindu Bhagavata and Vishnu Purana scriptures, where Lord Krishna battles a bear named Jambavan for more than 20 days. The reality that the authors unearthed is a little less mythical.

"We weren't able to find a single, clear, 100-per-cent-certain reference to the stone before 1750," Dalrymple reveals. "That was the biggest surprise – that so much of the tale about this diamond, which has been repeated over and over again over the last century and a half, is completely unsubstantiated."

What the pair did find within the scriptures, however, were warnings that diamonds are the bringers of death and avarice. "In early Hindu texts, you get the idea that diamonds can often be things that create violence around them. There are auspicious gems that bring good luck, but in Hinduism, diamonds have always brought bloodshed," Dalrymple explains.

"What is fascinating to see, is how that ancient Indian insight found its way into Victorian fiction with The Moonstone [Wilkie Collins' fictitious tale from 1868, considered the first detective novel] and now has become a very modern notion of the cursed diamond. They were aware that a diamond – something hugely valuable and attractive, but instantly transportable – was temptation in portable form."

Until the 1700s, when diamonds were discovered in Brazil, every diamond in the world originated in India, with the exception of a few black diamonds found in Borneo. With so many gemstones at its disposal, India was home to the richest and most lavish royal courts, brimming with gold, jewels and diamonds, causing visitors to write home with lofty descriptions of the treasures they had seen.

Inevitably, such wealth brought unwelcome attention, and in 1526, Babur (a descendant of Genghis Khan) swept down from Turan (now Uzbekistan) and seized most of northern India, establishing a Mughal empire that would last for the next 200 years. While fond of jewels, the new rulers brought with them a Persian preference for rubies. "They thought that diamonds were slightly vanilla," quips Dalrymple. "There are all these legends about the Koh-i-Noor appearing in courts," he continues. "But actually, the first reference we found of it is when the Persians pinched it from the Mughals in 1739."

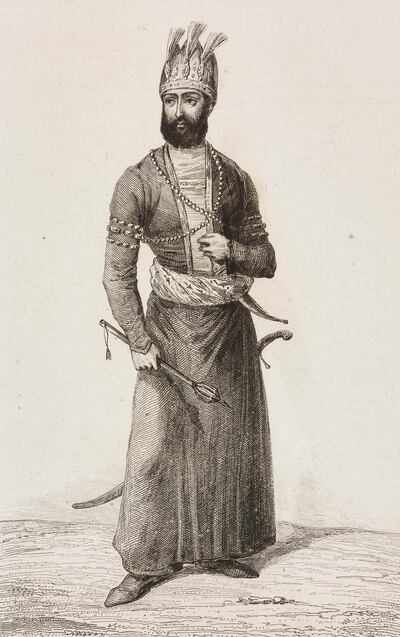

The theft he is referencing is when Nader Shah of Persia invaded northern India, overthrew its ruler, Muhammad Shah Rangila, and ransacked Delhi. As well as emptying the famed Mughal coffers, Nader Shah helped himself to the magnificent Peacock Throne, built by Shah Jahan. Only when Nader had the throne dismantled and sent back to what is modern-day Iran, is any mention made of the two impressive gems that had topped it. Having taken to wearing gems on armbands as a sign of kingship, Nader Shah wore the Timur ruby, and a large, uncut diamond that he is rumoured to have named the Koh-i-Noor, meaning "mountain of light" in Persian.

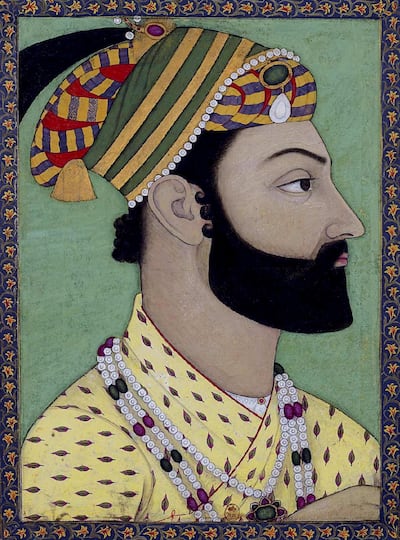

Despite his new-found wealth, Nader Shah was unable to enjoy it for very long, and in June 1749, he was murdered by his own troops. In a bid to uncover the whereabouts of the Koh-i-Noor, his grandson Shah Rukh was gruesomely tortured and had molten gold poured over his head. In fact, the stones had already left Iran for Afghanistan, smuggled over the border by Ahmad Shah Durrani, who was named the amir in 1747. While successful in holding onto the diamond, he was eventually killed in 1772, by a tumour that devoured his face. In 1801, his grandson, Shah Zaman, was overthrown as the ruler, and when he refused to hand over the infamous Koh-i- Noor, he was blinded with hot needles.

In 1803, Zaman's brother Shah Shuja was named amir, but just six years later, he ran afoul of his countrymen when he signed a pact with the British. Forced to flee to India, he turned to the maharaja of Punjab, Ranjit Singh, for protection, who asked for the Koh-i-Noor in exchange for guaranteeing Shah Shuja's life. "This is a diamond that has changed hands violently time after time after time, wreaking bloodshed, revenge and horror wherever it goes," Dalrymple says. "It is the bloodiest tale and it is surprising that something so small and pretty can create so much dissension."

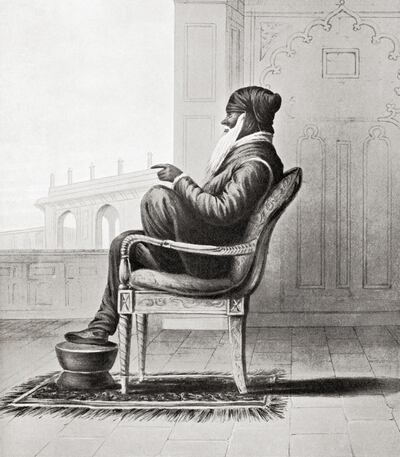

A strong and respected leader, Ranjit Singh was known for inclusive policies and social reform, and a military prowess that earned him the nickname "The Lion of Punjab". Heralded as the man who brought the diamond back to India, his hold on power was unshakeable. However, by the mid-1800s, India was faced with a new enemy: the British Empire.

Although Ranjit Singh was able to hold the colonisers at bay, his death in 1839 triggered a period of instability that saw four successive sons take the throne, only to be murdered shortly thereafter. Stability of sorts was restored in 1843, when the ruler's only surviving son, the infant Duleep, was named as maharaja, but by this time, the East India Company had exploited the turmoil to manoeuvre its way to prominence. Duleep's youth was used as an excuse to force him into signing the Treaty of Lahore in 1846, which placed the little king under British protection.

Two years later, the governor general of the East India Company, James Dalhousie, manipulated the start of the Second Anglo-Sikh War, which, when it ended, saw Duleep's kingdom destroyed and annexed to the British. Alone and helpless, the 10-year-old ruler was stripped of his wealth, his lands and his power, and as a final humiliation, made to hand over the Koh-i-Noor to the East India Company.

In an ironic twist, the company watched in horror as Dalhousie presented it as a gift to Queen Victoria, earning himself a lordship. Now under British rule, the stone travelled to England to be displayed at The Great Exhibition in London in 1851. Eager to see the famous gem, six million people, one-third of the country's population, queued up for a glimpse.

However, as with much of the history of the stone, things did not go quite as planned. Used to seeing diamonds cut and shaped to reflect light, the crowd was disappointed by the large but dull-looking uncut stone. Despite attempts to make it sparkle, the diamond, although weighing an impressive 190.3 carats, was declared to be no more impressive than a lump of glass. In desperation, Prince Albert ordered the stone to be recut. He commissioned Coster Diamonds to take on the task, which in turn brought in Dutch experts Levie Benjamin Voorzanger and J A Feder. Assured that despite an internal flaw, none of its impressive size would be lost, the prince gave assent for work to commence. However, when finished eight weeks later, at a cost equivalent to £1 million (Dh5.2m), the Koh-i-Noor was almost unrecognisable. Although cut into a dazzling oval, it had been slashed to almost half its size, to a mere 93 metric carats. No trace has been found of the removed pieces. Queen Victoria took to wearing the newly cut gem as a brooch, making her the last ruling monarch to wear it.

Today, the Koh-i-Noor sits in the crown of the Queen Mother, as part of the front cross. It last made a public appearance in April 2002, when the crown was placed on top of the Queen Mother’s coffin at her funeral.

I ask Dalrymple what he thinks when he sees the stone today, behind bulletproof glass in the Tower of London. "I look at it and think: 'You little devil, you,'" he laughs. "It is difficult to see it sitting pretty, knowing the number of people that were tortured. When you know the history and you look at it, you think: 'How can a small piece of carbon have such a fantastically explosive effect on the human psyche?'"

Today, despite being only the 90th largest in the world, the Koh-i-Noor is arguably the most famous diamond in existence. It has been the subject of numerous petitions for its return. One of the first acts of a newly independent India was to request that the diamond be given back, a demand that was repeated when Queen Elizabeth II took the throne. In 1976, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto requested that the stone be returned to Pakistan, while India tried again in 1990 and 2000, the same year that the Taliban entered their own request. In 2015, barrister Jawaid Iqbal Jaffrey demanded its return to Lahore. All requests have been resolutely denied. It seems, for now at least, the famed diamond is staying exactly where it is.

"It's a very difficult thing to say what is the Koh-i-Noor's rightful place," concedes Dalrymple. "That is something we have very much avoided doing in the book, because this is a diamond that has passed through the hands of whoever has been most powerful at that time. There are currently five countries that claim it, so its peaceful moment on its velvet cushion might not be there for much longer. The Koh-i-Noor has never been a quiet stone, and I think it has no intention of being so now."

_______________

Read more:

A look back at the history of the tiara

The extraordinary gifts India gave to an English prince in 1875

Fascinating story of princess Sophia, the granddaughter of the warrior-king Ranjit Singh

_______________