In a small framed photograph in the living room of a flat in Brixton, young Zineb Sedira is pictured in her father’s arms surrounded by three older siblings.

The family would grow from that moment captured in circa 1965 to include five more children but Sedira’s favourite was always Farida, on the left of the image, hands clasped in front of her white dress and looking slightly off camera.

As the eldest, Farida was the only one born in her parents’ native Algeria before, daring to dream an emancipatory dream, they left their conflict-torn country for a better life.

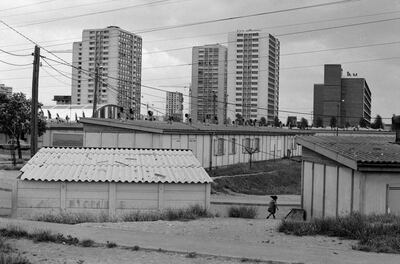

Looking back, Sedira, now 60, regards that promise of a more hopeful future to have remained largely unfulfilled not least because of its backdrop - a housing estate in the neglected Parisian suburbs.

“It was where all the immigrants were, particularly the North Africans and sub-Saharan Africans,” the acclaimed photographer and video artist tells The National. “In a kind of ghetto.”

There was, however, a strong sense of community among the immigrant families in the Gennevilliers commune that lends a bittersweet tinge to the memories that Sedira shares.

“We were a lot of Moroccans, Tunisians and Algerians. Our house was always full of mothers who came with their children,” she says.

She was born in 1963, just after the end of the eight-year war of independence in which an estimated 400,000 Algerians died.

Despite the vast number of refugees - Algerians, Jews and European settlers - who poured in from the Mediterranean seeking refuge, Sedira evokes a period in which France’s defeat as a colonial power had all but been erased from collective memory.

“In the 1960s and 1970s, when I was at school, they didn’t call it the Algerian War. The teachers referred to it as: ‘The events’, which minimalised the brutality of the conflict.”

Nonetheless, the Sediras acutely felt the conflict’s repercussions daily. They, as with many of the displaced, were marginalised and even the young Zineb noticed the “enormous amounts of racism around me”.

Her parents, previously freedom fighters in Algeria, became a factory worker and homemaker after crossing the Mediterranean Sea by boat.

Much to Zineb’s irritation as a child, they were never addressed using the respectful vous, as is common when speaking to strangers in France, but in the informal tu as an expression of their subordination.

Family holidays to the countryside in Algeria came as a welcome relief, where she especially recalls the house of her grandmother. It was basic, but Zineb loved it.

With no schools in the region during colonisation, knowledge was transmitted orally, and her own storytelling skills were honed at the feet of her grandmother and mother, who habitually recounted tales, real and imagined.

But the complicated interplay between belonging, displacement and integration was also revealed cruelly to the brood of siblings who were taunted as foreigners on their stays in what Sedira regarded as their homeland.

“Some kids threw stones at us and told us to go back to where we came from,” she recalls.

During her teenage years in Paris, she strongly identified with the struggles for freedom and social justice in the lyrics of the funk and rhythm & blues played by Afro-American musicians.

Her fondest memories are of the Thursdays, when school was closed, and her lifelong love story with cinema began with visits to Les Variétés with her father.

In that magical space, the two would watch Hollywood blockbusters and Egyptian melodramas full of music and dance, although the Italian epics and Spaghetti Westerns were to have the greatest impact.

Later, she would be drawn to Cinema Jean Vigo with its art-house offerings and militant, anti-colonial movies.

Sedira went on to use the medium of film to striking effect decades afterwards in an homage to cinema in Dreams Have No Titles, which she first presented at the Venice Biennale - widely regarded as the most important event on the arts calendar - in 2022.

It is a cautionary tale that relates her own family’s migrant experience, encompassing the relentless discrimination in France and Algeria that took a toll on all of them but particularly on Farida.

Sedira remembers being told the news of her sister’s suicide over the telephone. Plagued by what she describes as a mal de vivre identitaire - an existential discomfort with her own identity - Farida had killed herself at 19.

The Biennale was the first time that Sedira had revealed the tragedy in public. “People were surprised, even though I’m known for making autobiographical work. I don’t shout from the rooftops about it. This is the kind of thing that you only talk about when you’re ready.”

Shot largely within the sets she built inside the French Pavilion, the film brings together two common strands in Sedira’s artistic work: the personal and the political.

The year 2022 marked the 60th anniversary of Algeria’s independence, prompting Sedira’s decision to connect her own narrative to the country’s revolutionary cinema culture.

Her film incorporated footage from the Italian filmmaker Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1963), which was banned in France and then struggled for decades to find distribution. “I saw it for the first time when I was at art school in London, in the mid 1990s,” Sedira says.

After 1962, the country became a hub for left-wing filmmakers from around the world, who congregated at the Cinematheque d’Algiers, a cultural centre for cinema, and the Pan-African film festival of Algiers in 1969.

“The Sixties are really an important decade, because there was strong international political consciousness that was anti-capitalist and anti-colonial,” she says.

Sedira began exploring this chapter in Algeria's history for her exhibition A Brief Moment at the Jeu de Paume in 2019 for which she was shortlisted for the prestigious Deutsche Borse Photography Prize.

“Algiers became the liberation capital of the 'Third World' with a strong emphasis on Pan Africanism. What did it mean for an Algerian to discover his African-ness? Under colonialism, he knew the country had a north and a south. But, suddenly, he discovered that the country was huge and the people had their own cultures.”

It is telling of social mobility in France that the first woman and first artist of North African descent to represent the country at the Biennale had been an expatriate in London for more than 30 years.

“I thought: finally France takes steps to modernise. The UK has been presenting women artists in Venice for over 20 years,” she remembers thinking on learning of her selection.

Sedira moved to London in 1986, aged 23, partly prompted by wanting to distance herself from the constant questions of identity.

Had she remained in France, she thinks she might not have become an artist at all. “It was only a certain elite who went to art schools there,” Sedira says.

But the main reason for relocating was a desire to learn English “while partying”, and a passion for music, particularly jazz and blues.

Coincidentally, she ended up living opposite an island of green parkland that was named after the pioneer bebop drummer Max Roach, in a Victorian terraced house on one of the UK’s most squatted streets.

She was quickly absorbed into the British Black Art movement. Her friendship with the British Afro-Caribbean artist Sonia Boyce, who is a neighbour in Brixton, endures to this day. Boyce became the first black woman to represent the UK in Venice - in the pavilion next to Sedira’s - and won the festival’s top award, the Golden Lion.

Sedira enrolled at Central Saint Martins in 1992 to study fine arts and pursue photography because it was the medium with which she could best express herself.

She still uses the battered old Olympus picked up at a market 40 years ago, conceding that “it’s the only camera that I know how to use”.

But she soon found herself making films and installations while doing a masters at the Slade and, later, at the Royal Academy.

Early works often featured the women in her family in explorations of generational links and migration. Mother Tongue (2002) sees a conversation between Sedira, her mother and daughter with each speaking her own native language - French, Arabic and English, respectively.

Another recurring theme is the sea that evokes not only her parents’ migration but Sedira’s own to the UK by boat before the Eurostar existed.

During a work trip to Mauritania in 2009, she developed a photographic series and film installation based around a maritime graveyard that is also an embarkation point for refugees from Africa to Europe. “I found myself between the desert and the sea, with abandoned boats on the beach. It was apocalyptic and somehow magnificent,” she says.

Her latest solo exhibition Can’t you see the sea changing? is on display at the Dundee Contemporary Arts in Scotland, and features parts of her London studio, including a collection of souvenir boats and other seaside town memorabilia.

“The sea is often seen as a space of freedom, but it can also be a barrier,” she says, in reference to the many victims of dangerous sea crossings from the Middle East and Africa.

Sedira was still a student when she became a mother, and raised her first two children alone for 12 years until some pressure was eased by a new partner who fathered her youngest daughter. “Motherhood made me more focused,” she says. “There was no messing around,” she adds in English to underscore her work ethic.

“I didn’t waste time with other students at cafes or pubs. It gave me an important structure. I slaved away. I was really, really tired. But it also gave me that fighting spirit, that motivation.”

With the children all grown up now, Sedira made the perhaps surprising decision recently to move her studio to Paris where she says the cinema scene affords more opportunities.

“There’re a lot of art-house films being made and access to cinema is more affordable than in London.

“I’ve reached the age where I want to go back to my roots but also my Algerian community and family. London is getting too expensive and more difficult. In Paris, life feels a bit easier, gentler. If you have some money, it can be pleasant - the restaurants, the terraces.”

She hopes to find a rhythm, perhaps dividing her time between three weeks in Paris, one in Brixton but “it’s hard because I’m always travelling - whether it’s Tunisia, Berlin or Bali…” she says, trailing off as though the list might be never-ending.

As we sit in her flat, the sunshine pours in through the large arched windows opposite, bathing the family photo featuring her beloved Farida on a low side table in shafts of light.

It might otherwise be easily missed amid the abundant decor of the 1960s-themed room, replete with plants, antique furniture, cinema posters, hand-woven rugs, and bits and pieces collected from flea markets.

All of it was recreated for the Venice Biennale as an installation to invite people to immerse themselves in Sedira’s story by sitting on the sofa or flicking through the pages of a book.

“Making an installation out of my living room is an autobiographical act. There are pictures of my father, my mother, of Makkah, intimate photos, and traces of my life as a mother and artist in Brixton,” she says. “I’ve had so many dinners and parties in here. We dance, play vinyls.”

Sedira is an inveterate dancer. In childhood, her father used to ask her to dance to Algerian music for a symbolic sum, and she would create the setting from whatever was to hand to stage a show.

For Dreams Have No Titles, she had considerably more artistic budget to design a boîte, or nightclub, in which she recreates a tango, echoing a scene from Le Bal by the great Italian director Ettore Scola.

“I played in it,” she says, "and I invited my friends who are artists and curators to play in it, too. They’re my artistic community, my family.”

The vast number of people who have viewed the film plots a spectacular trajectory from her indulgent paternal audience of one in the gruelling French suburbs to the heights of the international art world.

It is a tale of survival, of taking one day at a time. As she says in a voice-over while shimmying in a yellow retro dress to Charles Wright’s Express Yourself in the final frames: ‘Just keep on dancing… dance to the tempo of life.’’