In recent years, the troubling trend of damaging – or attempting to damage – artworks has continued to be a tactic favoured by activists to protest against climate change.

While the intention behind such actions may be rooted in genuine concern about the environment or other issues such as animal rights, and in response to the anxiety a number of young people feel today, the ramifications are concerning.

Art plays a pivotal role as a medium for cultural expression and historical preservation. Yet, a series of incidents across continents is a reminder of the growing tensions between activism and the responsibility of a museum to bear stewardship of priceless collections.

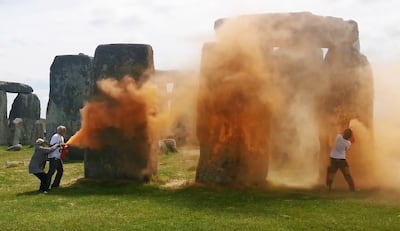

In the past month, there have been at least three major cases of defacement: one of a Monet painting in the Musee d’Orsay in Paris – not protected behind glass – and two others in the UK, including the new portrait of King Charles, and the cultural heritage site Stonehenge sprayed with orange powder.

One notable case that garnered international shock and anger was at the Louvre Museum in Paris less than two years ago, when an environmental activist group staged a protest in the museum against the lack of action on climate change. To amplify this message, members of the group attempted to deface several paintings, including masterpieces such as the Mona Lisa. It was clear from the media statements and comments from the public that they overwhelmingly considered this vandalism which in effect, tarnished the reputation of the cause they purported to champion.

According to some reports, in 2022, there were 38 attacks on artworks by climate protesters. Similarly, in 2023, the Tate Modern in London became the target of activist outrage when a group advocating biodiversity conservation took issue with the museum's funding partnerships with companies allegedly involved in environmental degradation. In their act of protest, the group splattered paint across the walls of the gallery. The incident sparked widespread condemnation and reignited debates around the ethics of activism.

Beyond Europe, instances of art vandalism in the name of environmentalism have occurred frequently. In 2021, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City fell victim to such an attack when activists protesting fossil fuel investments by museum donors defaced sculptures and paintings. It was deemed vandalism and prompted a swift response from museum officials, who vowed to enhance security measures.

As a result, museums today increasingly protect their artworks behind panes of glass and have increased security in their galleries, as well as at entrances where bags are inspected.

While these cases represent a mere fraction of art vandalism by environmental activists in recent years, they highlight the need for dialogue and understanding between disparate stakeholders. Saving the planet is an urgent cause but resorting to vandalism for the sake of the planet is futile. It undermines principles of civil society and the relationship activists have with museums.

In a previous article for The National, I wrote about museums around the world being some of the few public spaces left to hold open discussions and protests, as a number of civic spaces become policed, inaccessible or restricted.

Protesters defacing art collections to garner attention only emphasises the important role museums play in society and their responsibilities to their communities. Museums must not act as isolated worlds but rather converse through programmes and exhibitions to echo issues in local and global discourse.

They are many among the public and even those within the museum community, however, who see the disfiguring of art as provocative but necessary measure to combat the apathy often observed in discussions surrounding climate change. They argue that this is the only way to effectively shine a light on climate change.

This viewpoint shows that art institutions and the public are increasingly acknowledging the interconnectedness of environmental issues with broader social and cultural concerns.

But this only highlights a small majority and I believe if the trend continues, activists could potentially cause museums to distance themselves and such groups will find that they are short of the allies they once had.

It is imperative, therefore, that activists reconsider their tactics and embrace constructive means of effecting change. Dialogue, engagement and collaboration are far more promising than destruction that breeds distrust.

Although in some incidents of vandalism, art works were protected by glass, the incidents made other museums, who do not have those measures, weary of not faring well if protesters entered their galleries. This understandable disquiet has likely resulted in two outcomes, neither of which are ideal for the future.

One is that without the funds to increase security or add protective measures to their most prized works, museum administrations may be forced to remove works from display or limit access to viewing them, which is unfair to visitors.

The other outcome is concern about a museum's legal liabilities to lenders that may result in loans terminated and/or future promised gifts retracted to ensure artworks are protected. Again, this puts museums in a difficult situation where they must figure out how to maintain relationships internally and externally and to err on the side of caution with regard to future attempts at vandalism.

If the defacement would stop, museums would be in a better position to foster a positive environment, strengthen community outreach initiatives and have more transparent practices. This, however, requires a relationship like any other: to be built on mutual respect and trust. It is in such a social contract that we can hope for a more sustainable, equitable and harmonious future for generations to come.