Beirut lies shattered again. In the aftermath of Tuesday’s devastating explosion at its seaport, swathes of one of the world’s most beautiful cities now look like scenes from the apocalypse. “A peninsula that seems to have fallen to earth from the heavens”, as the late Lebanese writer Samir Kassir described the city of his birth, suddenly resembles an urban hell.

It shouldn’t be like this. But Beirut isn’t like most other cities. You don’t have to dig too deep beneath its voluptuous setting below Mount Lebanon, past all the partying and shallow snapshots, to discover the self-destructive DNA that time and again wreaks havoc here. Poisonous neighbours merely deepen the wounds caused by sectarian division and the endemic corruption of Lebanese politicians, whose self-enriching misadventures prior to the pandemic had already brought the city to its knees. This time the blood of Beirutis is on their hands, the port explosion a terrible emblem of their broken system. Beirut may be sun-kissed, sybaritic and welcoming, but it is also dangerous, blood-stained and cruel.

In Sentimental Archives of a War in Lebanon, a collection of poems published in 1982, the late Lebanese poet Nadia Tueni unleashed a barrage of barbs against the civil war propagandists who were destroying the city she loved. "Those who live in the sunlight of the word," she wrote, "upon the runaway horse of slogans, those, shatter the windows of the universe." Today Beirut's windows, not to mention its port, shops, restaurants, houses, hospitals and the lives of its long-suffering population, have been smashed to pieces by indolence, incompetence and corruption. Had she lived today, Tueni would have eviscerated this generation of Lebanon's ruling class, political pygmies and kleptocrats par excellence.

Beirut’s recurring tragedies, including this latest entirely avoidable disaster, somehow seem worse in the context of the city’s almost indecent natural beauty. This should really be a paradise on earth, the geography and climate tell you. When they made the town a colony in 14 BC, the Romans named it Colonia Julia Augusta Felix Berytus, in honour of the emperor Augustus’s daughter and in recognition of this “happy shore”. Visitors approaching the port in the nineteenth century, the beginning of Beirut’s heyday, found their eyes drawn inexorably to the cypresses, carobs, sycamores, prickly pears, figs and pomegranates of the tiny town, then to the banana trees, gnarled olives, oranges, lemons and mulberry groves beyond it and up towards the sturdy pines on the lower slopes of Mount Lebanon.

The port that now lies pulverised by the explosion of 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate was the lifeblood of Beirut ever since the invention of steamships in the early nineteenth century transformed what was then a dingy medieval hovel into a flourishing westward-looking city, the last word in urban grace and glamour. Beirutis’ longstanding genius for trading saw the city thrive on Mediterranean commerce, exporting silk and raw materials and importing the products of the world, from cotton shirts made in English mills to Brazilian coffee.

Beirut’s meteoric rise happened so quickly that it astonished the city’s own residents. In 1824, just 15 ships entered its harbour. Then, in 1835, Mahmud Nami Bey, president of Beirut’s advisory council, built a new jetty and within three years the number of ships calling in had rocketed to 680. Customs receipts quadrupled between 1830 and 1840. From 50,000 tonnes a year in the 1830s, total shipping entering Beirut soared to 600,000 tonnes in 1886. Between 1889 and 1894, the port, by now the engine room of the city’s prosperity, was comprehensively modernised and enlarged with a new quay, jetty and warehouses. With breakneck speed the city became one of the most cosmopolitan on earth, its polyglot population shooting up from eight thousand in the early 1830s to around 130,000 on the eve of the First World War.

In an era when Beirut’s leaders actually served the city rather than bleeding it to death, infrastructure and sanitation were improved, paved streets were introduced, a lazaretto was established to provide quarantine facilities and port and customs procedures were regularised in a wave of modernising reforms.

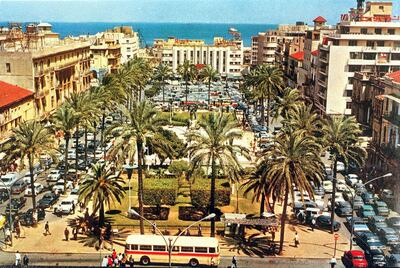

Christians and Muslims alike made their fortunes as merchant families. Beirut was buzzing. Under Ottoman rule Yusuf Aftimos, Mardiros Altounian and Bechara Affendi became the founding fathers of Lebanese architecture. Inaugurated as the seat of local government in 1884, the Petit Serail on the northern side of the famous Burj square became an elegant backdrop for promenaders in the Hamidiye public garden named in honour of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. His reign from 1876 to 1909 brought new schools, hospitals, police stations, drinking fountains, a post office, lighthouse, racecourse and train station to the city. Visiting in 1898, Kaiser Wilhelm II and his wife Augusta Viktoria, the last German emperor and empress, were so impressed they pronounced Beirut “the jewel in the crown” of the Ottoman sultan. That was some achievement.

Beirut’s golden era on the world stage did not die with the 19th century. In 1900, Orosdi Back, a department store that drew comparisons to Harrods in London, opened its doors for the first time. What better way to kick off the 20th century than with this triple-domed temple to consumerism, part of a massive gentrification project on a landfill site where the quay met the port’s warehouses and customs offices on Rue de la Douane?

The Paris of the East dazzled, continuing its reckless money-making and revelries as the decades passed. Fleeing imminent war in Europe, my grandmother and grandfather succumbed to the allure of Beirut, where my father was born in 1938. In the 50s and 60s, the Saint George Hotel rocked to parties attended by glitterati from the Aga Khan and Brigitte Bardot to David Rockefeller and the British spy Kim Philby, while the rival Phoenicia Hotel, a two-minute drive down Avenue Fakhreddine, hosted celebrities like Marlon Brando, Umm Kulthum, Fairuz and Catherine Deneuve. It was, Kassir wrote, “as if, when talents were distributed among Arab cities, the fairies decided that Beirut was to be the capital of relaxation and easy living”.

And then the agonies of the civil war of 1975 to 1990 brought the curtain down on the fun and games.

Yet Beirut, like Baghdad, has developed an extraordinary, phoenix-like ability to pick itself up off the floor, dust itself off and rebuild. It did it after 1990, when parts of the city were in complete ruins, and it did it again after the Israel-Hezbollah war of 2006.

Now, as the world watches aghast at its latest ruination, we must recall another Tueni poem, written four years into the civil war. Whether Beirut is a courtesan, scholar or saint, she wrote, “elle est mille fois morte, mille fois revecue”. She has died a thousand times and been reborn a thousand times. With or without her criminally negligent politicians, she will rebound from this latest disaster.

Justin Marozzi is the author of Islamic Empires: Fifteen Cities that Define a Civilization, published in paperback on 6 August.