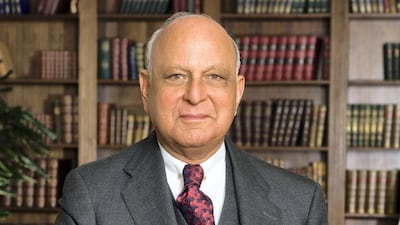

Once in a lifetime, you meet someone who combines a brilliant mind, a kind heart and incredible charm. Nemir Kirdar – the founder, former executive chairman and CEO of Investcorp – was that type of person.

While Kirdar is recognised globally as a pioneer in private equity and in finance, his influence and interests spanned much further than the financial world. Sadly, Kirdar passed away this week after an illness. He left behind the best legacy a person could hope for: an impeccable reputation.

In a 1993 profile marking Investcorp’s ten-year anniversary, the International Herald Tribune wrote of the company’s “gold-plated reputation among New York bankers”. That gold-plated reputation was due largely to Kirdar and the ethos with which he infused Investcorp.

Many CEOs spoke of values. Kirdar lived them.

Kirdar was an Iraqi who belonged to a bygone era – one for which many of his compatriots are nostalgic. He was a monarchist, but also one who believed in Iraq’s potential.

I had the good fortune of discussing the country many times with him, including during the period in which he was writing his book, Saving Iraq, which was published in 2009 and called for the building of state institutions and more investment in Iraq's youth.

As a journalist, you never forget those who are generous with their time and information, especially when you are working hard to build your name and portfolio of interviews. Despite the fact that I was at an early stage in my career at the time, Kirdar accepted my request to interview him for a long profile in 2007.

The interview was our first meeting, conducted at his grand offices in the Investcorp building in London’s Mayfair. There were mahogany bookcases, large windows and a corner seating area. Even though I had sent a short biography in advance, Kirdar asked me to tell him about myself before we began recording the interview, focusing on my Iraqi roots and what I had studied. I told him that I had recently completed my MA in history, with a focus on the 1958 coup d’etat that ended Iraq’s monarchy.

He immediately sat up. “You said coup – not revolution. Why?”

I replied that it was indeed a bloody coup, and not an uprising by the people. Kirdar was impressed with this language because it reflected an understanding that the Iraqi people did not, in fact, rise up against their king, Faisal II – a man who also happened to be Kirdar’s personal friend.

The coup that took place on July 14, 1958 changed Iraq forever and took the country down a route of decades of turmoil. King Faisal II, still in his teenage years, was brutally killed, along with his family. Kirdar never stopped mourning him. He had been waiting to meet up with the young monarch in Istanbul when news of the slaughter reached him. In his office in London, he spoke to me at length about his personal loss, but also that of Iraq with the ending of its monarchy.

Ironically, Princess Badiya bint Ali, the sole surviving member of the Iraqi royal family, passed away exactly a month before Kirdar. The few final links to Iraq’s monarchy are fading away permanently.

My first interview with Kirdar in June 2007 was meant to last one hour. It became three. Over half of that time was off the record, discussing Iraq, its past and at that time its troubled present with the American occupation. Running over on his schedule was not something Kirdar did lightly, but equally, he took his time to really connect with people.

That initial discussion became a foundation for many more conversations. He once told me, “Your time is your most valuable asset. Spend it wisely.” He made a point of dedicating time to his beloved wife, Nada, and his two daughters, regardless of how busy he was.

Kirdar’s network of friends, acquaintances and business contacts was unparalleled, and yet he didn’t only seek out those in power. Rather, he deliberately sought out those who could present a new or different way of looking at world affairs.

His famed “Strategic Partners Meetings” became gatherings of some of the most interesting people from all over the world. I had the good fortune of attending a number of them. These high-level, off-the-record retreats would collect some of the greatest minds in the world to discuss a variety of topics in an intimate setting. There was a strict cap on the number of attendees. At one such meeting, in Rome, the programme included a private, night-time tour of the Vatican.

Anything Kirdar did, he did with style. He loved the finer things in life (and indeed had earned them), especially great food with a beautiful ambience – from Harry’s Bar on London’s South Audley Street, to Cafe Milano in Washington’s Georgetown. But he equally appreciated simple delights, like stopping for a shawarma sandwich in between meetings in the many Arab capitals he frequented.

Kirdar also made several contributions to the advancement of knowledge. He made generous donations to universities like Georgetown and Harvard. And served as an honorary fellow at a number of others. He sat on the board of Brookings, and wrote a number of books.

Professor Roger Goodman, Warden of St Antony's College at Oxford, wrote, "Between the Investcorp Building and the Kirdar Building, Nemir Kirdar has left an enduring mark not only on St Antony's College but also the University of Oxford through the Middle East Centre. Future college histories will record him as one of our greatest and most generous benefactors".

Kirdar’s legacy lives on in his reputation and his incredible work. Even his retirement was characterised by his signature elegance. He handed the executive reigns of his beloved Investcorp to Mohammed Alardhi in 2015 and stepped down from its board in 2017, restructuring the organisation’s leadership to ensure its success and resilience after him.

The last time I saw Kirdar was very brief, at the funeral of another great Iraqi-Briton, Zaha Hadid, in London in 2016. A friendship tied them together, as did the Investcorp Building housing St Antony’s Middle East Centre. Gifted by Kirdar, it was designed by Hadid. They are both icons in their own right, and the best examples of Iraqis who shone abroad but whose hearts remained tied to their homeland.

Mina Al-Oraibi is editor-in-chief at The National