If the pundits are right, Sunday night’s Academy Awards should see the first Oscar go to a film about an expert on relativistic cosmology.

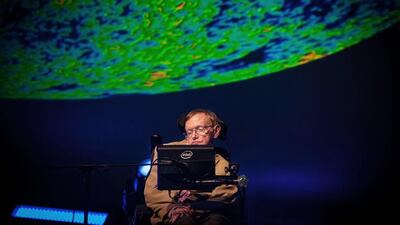

Most people know professor Stephen Hawking as the wheelchair-bound physicist whose inspiring life story is the subject of The Theory of Everything, which is in the running for five Oscars.

Not surprisingly, the movie spends little time on Hawking’s scientific work, except to hint at its cosmic implications. Yet by a weird coincidence, a breakthrough has just been made on the problem investigated by Hawking in real life: why does our universe exist?

The film opens with Hawking as a research student at Cambridge University in the early 1960s, searching for a problem to solve for his doctorate. He ends up trying to find out how – as the movie puts it – “the universe was born from a black hole explosion”.

This doubtless will cause the cognoscenti to wince, but may also prompt frowns even from those unversed in the physics of space-time. After all, surely black holes suck rather than blow?

As objects with gravity so strong not even light can escape, black holes are not the most obvious place of origin for a universe. Indeed, the film understates the size of the mystery tackled by Hawking. He was interested in the nightmarish object that lurks at the very core of a black hole: the space-time singularity.

This is the point where all the mass of a black hole is concentrated – and being a point, it has zero size and thus, infinite density. Not even Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity – general relativity – can cope with what happens there.

Asked about the properties of a singularity, its equations are as much use as a pocket calculator asked to divide one by zero.

The early years of Hawking’s career went beyond ordinary black holes to find out if the same problems afflicted the theory when applied to the entire universe. Did it, too, have a singularity from which – on the face of it – nothing could emerge: not stars, nor planets, or us, because of its fierce gravitational pull?

Shockingly, Hawking found that it did. Many researchers would have been content to be remembered simply for that.

In the decades that followed, however, Hawking went farther. Among scientists he is best known for proposing that – in contradiction of common sense – black holes really can explode.

While no one has yet seen this happen, few scientists doubt his claim, which involves marrying Einstein’s theory of gravity to quantum mechanics, which governs the subatomic world.

Yet the question raised by Hawking’s 50-year-old theory remains unanswered. If the universe really did begin in a singularity of infinitely strong gravity, how come any of us are around even to ask?

Now, just as Hawking’s life becomes known to millions through this biopic film, theorists think they have made progress with this question.

It has been achieved by showing there must be something missing from Hawking’s proof.

In a sense, that much is obvious: the very fact you are reading this article proves the universe cannot have begun in a singularity, with an infinitely strong gravitational field.

So what did the 20-something Hawking overlook in his proof?

That's what theorists Dr Ahmed Farag Ali and Dr Saurya Das identify in a paper this month in the journal Physics Letters B.

Like all proofs, Hawking’s is based on assumptions, and the research suggests why these might not hold true. The reason is linked to quantum mechanics – the same branch of physics that led Hawking to make his claim that black holes can explode.

Put simply, Dr Ali and Dr Das show that Hawking’s original theorem assumes that particles follow paths through space and time that are unaffected by the laws of the subatomic world.

Once these quantum effects are taken into account, there is a limit to how closely packed particles can become. This has profound consequences for understanding the very early universe. It allows it to be extremely dense but never infinitely so.

As such, in the real universe, the dreaded “initial singularity” can never occur, which means that stars, planets and the human race can.

While it is comforting to know that the laws of physics do at least allow us to exist, the new research has other, more exotic, implications. First, it casts light on another cosmic mystery that has puzzled scientists since it was first identified almost 20 years ago – dark energy.

Studies of the distant universe have shown that it is still expanding, 14 billion years after the Big Bang. Once thought to be just the result of momentum, this expansion is now known to be accelerating – as if the universe is propelled by an invisible power source.

Until now, the origin of this dark energy was unclear. According to the new research, it is an inevitable consequence of the same quantum effects that prevent the initial singularity.

But the most intriguing implications concern a question even Hawking himself once dismissed as unanswerable: what happened before the universe began?

In his famous best-selling book, A Brief History of Time, Hawking dismisses the question as being as senseless as asking what lies north of the North Pole.

Ironically, the new findings breathe life into an idea hotly debated when Hawking was a student: that the universe has lasted for ever.

Hawking himself had wanted to study this possibility with a Cambridge professor renowned for his ideas. To his frustration, he ended up working on something seemingly less exciting: cosmic singularities.

But the Cambridge professor’s ideas were wrong, and now the study of singularities has opened the way to the universe lasting for ever – so Hawking had been on the right path after all.

It is tempting to say a cosmic power must have been at work. Perhaps it will also lead The Theory of Everything to Oscar glory.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Reader in Science at Aston University, Birmingham