The setting is spectacular but the subject is strange. Inside a magnificent Victorian building, amid the natural splendour of Adelaide Botanic Gardens, is a tourist attraction that was once common around the world, but is now one of the last of its kind.

Surrounding visitors is fake fruit, plastic fungi, petrified bread, endless plant samples and, most notably, jars full of unusual herbs.

This is the quirky Santos Museum of Economic Botany, which opened in 1881 to teach visitors the many ingenious ways humans use plants.

Back then, there were similar museums in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne, and major cities around the globe.

In the late 1900s, the study of economic botany waned and these museums disappeared. What makes this Adelaide attraction so remarkable is that its delightfully old-fashioned interior is mirrored by its exhibits.

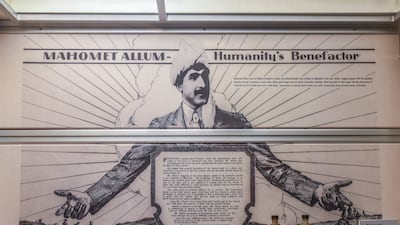

Many of its displays have not been changed since nearly a century ago, when the museum’s collection of herbs inspired the career of one of Adelaide’s most unique historical characters, Mahomet Allum.

By harnessing the medicinal powers of plants, this Afghan healer became an Australian celebrity known as the “wonder man”, treating thousands of patients while working until he was nearly 100 years old.

His fame, success and unusual methods also made him a controversial figure.

Allum’s extraordinary tale echoes through two other Adelaide attractions: its impressive Migration Museum, which has an exhibit on his life, and the place where he prayed, the historic Adelaide Mosque.

His story also helps to explain the rich Islamic history of Adelaide.

Now a modern city of 1.3 million people on Australia’s southern coast, South Australia's capital city was only a small town when its first influx of Muslim immigrants arrived in the 1880s, mostly from Afghanistan and India.

Allum was among the hundreds of men who came to Australia to work as cameleers, using the animals to move goods, chart new trade routes and locate fresh agricultural land.

They also built Australia’s first mosques. Along the fringe of Adelaide’s shady Whitman Square Park is a quartet of whitewashed minarets, contrasting against a deep blue sky and the dark brown stones embedded in the facade of Adelaide Mosque.

Australia’s oldest functioning mosque, it was built in 1888. Soon after, it became known in Adelaide for its music-filled Eid festivals and for its many Muslim herbalists, called hakims.

These men created herbal remedies by mixing ingredients imported from Afghanistan and India — wormwood, turmeric, senna leaves and dried figs — with Australian products such as honey, butter, rose petals and beetroot leaves.

The cures they sold were new and unique to the people of Adelaide. The herbal remedies also arrived at a time when Australians were increasingly distrustful of traditional medicine.

This information is presented in the Migration Museum alongside an exhibit dedicated to Allum, the most renowned herbalist in the city’s history.

The fascinating museum traces the history of Adelaide’s many different ethnic groups and the effect of its most influential migrants.

Allum was born in Kandahar in 1858. In his late twenties he moved to Western Australia, where he worked as a cameleer, a job that took him all over the country and eventually to South Australia.

In the early 1920s, Allum lived in a house 200 metres from Adelaide Mosque, where he prayed daily. It was from that home that he made a major change late in life, opening a herbalist practice at the age of about 70.

As the Migration Museum explains, people travelled from all over Adelaide to try his cures for pain, inflammation and insomnia. Many were astounded by their efficacy, leading to Allum’s “wonder man” nickname.

On display in the museum are two original bottles of Allum’s most popular product, which he called blackjack. A blend of honey and senna pods, it was claimed to rid its consumer of indigestion.

Soon Allum was reportedly treating hundreds of people a week.

To build on this success, he paid for eye-catching advertisements in Adelaide newspapers. He became so well known and appreciated that, after he made a trip to his native Afghanistan in 1934, about 10,000 Adelaide residents signed a petition urging him to come back to their city.

When Allum returned, he received a warm welcome from his customers and a harsh blow from Australian authorities.

In 1935, he was charged with falsely claiming to be a medical professional. His trial was big news in Adelaide. Critics described him as a conman who sold useless placebos.

But Allum had many more fans than detractors. A huge number of witnesses came forward to defend him and, after paying a fine for misleading advertising, he was permitted to continue his herbalist practice. Allum continued to treat patients well into his nineties

Remarkably, he lived to the age of 106. He was laid to rest in Centennial Park cemetery in southern Adelaide, where a small obelisk marks his grave.

Meanwhile, his colourful tale lives on in the Migration Museum, Adelaide Mosque and the Museum of Economic Botany, three of the city’s most intriguing tourist attractions