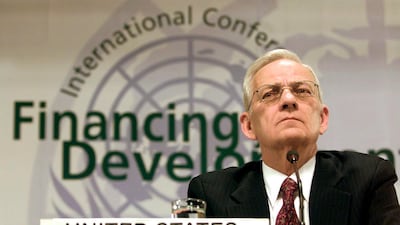

Former US treasury secretary Paul O'Neill has died at the age of 84.

A former head of aluminum giant Alcoa, Mr O’Neill served as treasury secretary from 2001 to late 2002.

He helped Wall Street reopen after the September 11 terror attacks and was instrumental afterwards in beefing up the government’s programs to disrupt financing to terrorist groups.

Mr O'Neill died at his home in Pittsburgh on Saturday after battling lung cancer.

After a few surgeries and chemotherapy, he decided against any further intervention four or five months ago, his son Paul O'Neill Junior said.

“There was some family here and he died peacefully,” he said. “Based on his situation, it was a good exit.”

Mr O'Neill had been forced to resign from his role after he objected to a second round of tax cuts because of their impact on deficits.

After leaving the administration, he worked with author Ron Suskind on an explosive book covering his two years in the administration.

Mr O’Neill had contended that the administration began planning the overthrow of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein after US President George W Bush took office, eight months before the September 11 terror attacks.

Mr O’Neill’s blunt speaking style more than once got him in trouble as treasury secretary, sending the dollar into a tailspin briefly in his early days at treasury when his comments about foreign exchange rates surprised markets.

In the spring of 2001, Mr O’Neill jolted markets again when during Wall Street’s worst week in 11 years, he blandly declared “markets go up and markets go down”.

He was more focused on the traditional treasury secretary’s job of instilling confidence during times of turbulence and later that year he led the effort to get Wall Street re-opened after the September 11 terror attacks.

In his book, Mr O'Neill had depicted Mr Bush as a disengaged president who did not encourage debate either at cabinet meetings or in one-on-one discussions with cabinet members.

He said the lack of discussion in cabinet meetings gave him the feeling that Bush “was like a blind man in a roomful of deaf people”.

He said major decisions were often made by Mr Bush’s political team and Vice President Dick Cheney.

Mr O’Neill had been recruited to join the cabinet by Mr Cheney, his old friend from the Gerald Ford administration.

But it was Mr Cheney who told O’Neill that the president wanted his resignation.

It was part of a move by Mr Bush to shake up his economic team and find a better salesman for a new round of tax cuts the president hoped would stimulate a sluggish economy.

When the book, The Price of Loyalty: George W Bush, the White House and the Education of Paul O’Neill came out in early 2004, Mr Bush's spokesman Scott McClellan discounted Mr O’Neill’s descriptions of White House decision-making and said the president was “someone that leads and acts decisively on our biggest priorities.”

Mr O’Neill said his purpose in collaborating on the book, for which he turned over 19,000 government documents to Mr Suskind, was to generate a public discussion about the “current state of our political process and raise our expectations for what is possible.”

After leaving the Cabinet, Mr O’Neill returned to Pittsburgh, where he had headed Alcoa from 1987 to 1999.

He resumed working with the Pittsburgh Regional Health Care Initiative, a consortium of hospitals, medical societies and businesses studying ways to improve health care delivery in Western Pennsylvania.

He also devoted time in retirement to projects that would deliver clean drinking water to Africa. As treasury secretary, Mr O’Neill had focused attention on poverty and combating diseases such as Aids in Africa, touring the continent with Irish rock star Bono.