For watchers of the US 2024 presidential campaign trail, the road most tangibly begins in Iowa.

Once every four years, the world's eyes turn to the small US state for an early milestone in the presidential election process: the Iowa Caucuses.

Republicans in the state will on Monday produce the first results of the party's race to solidify a challenger to US President Joe Biden in November.

The party says it's the initial step in their bid to “fire” the Democratic president.

And there lies a key factor in the significance of the caucus: being first thrusts Iowa on to a lofty public stage. But why does it capture so much interest?

Caucus v primary: What's the difference?

The caucus meets the same objective as a primary, but the process is distinct.

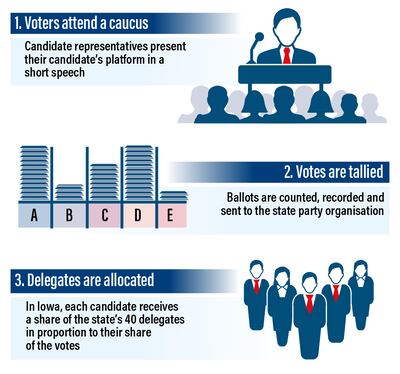

For one, a caucus is run by political parties, not by state governments.

And instead of primaries, where voters head to polls to vote for a candidate or submit absentee ballots, for example: Iowans go in-person to commune with fellow voters, listen to speeches from campaign representatives and write down names of their preferred candidates. A caucus can, in other words, be described as a party meeting.

Caucus volunteers collect ballots and send the results to the Iowa GOP, or Republican Party, where candidates then receive delegates based on the proportion of votes in their favour.

Iowans say there are strengths, and weaknesses, to the unique system that has been weeded out of the American political process in other states.

“As an Iowan, I love caucuses,” says Rachel Paine Caufield, director of the Iowa Caucus Project at Drake University, adding that convening with the community is “an opportunity to come together with neighbours and friends and family and collectively have conversations about where the party is and where the party is going”.

“It strikes me that there are very few places in our political life where we have those kinds of venues where we come together and talk to each other in a room,” Ms Paine Caufield adds.

But a caucus has its catches – the in-person mandate creates all-too-human hurdles.

They tend to have much lower turnouts than primaries, at about 20 per cent, in part because “it can be hard to participate in a caucus to get out of the house on a snowy evening and go meet neighbours”, says Ms Paine Caufield.

“We may have fewer people participate, but those people are more invested in the process. So it's kind of quality over quantity,” she argues.

Trump is likely to win. What else should you pay attention to?

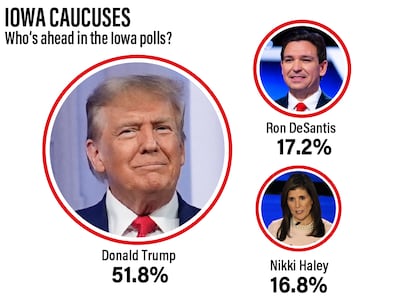

“There's no question about who is going to win the Iowa caucuses,” says Ms Paine Caufield, asserting: “Donald Trump is going to win.”

The former president has a stronghold in the polls, at 51.8 per cent of support compared to runner-up Ron DeSantis's 17.2 per cent and Nikki Haley's 16.8 per cent.

And Mr Trump is polling even higher nationally, at 61.3 per cent of Republicans, according FiveThirtyEight.

On Wednesday night, the former president's two most prominent challengers debated at Iowa's Drake University in an insult-laden wrangle over who should come second to Mr Trump.

Florida governor DeSantis and former Trump administration UN ambassador Haley both conceded that “Trump should be here,” but the Republican front-runner has dodged every debate so far in favour of his own town halls or online interviews.

The Iowa results may seem predictable, but they have the power to determine who the nation sees as a viable challenger to the right-wing former president as he faces a slew of legal battles over his candidacy, or who may take the mantle in 2028.

And because Iowa Republicans allow you to sign up to become a party member on the night of the caucuses, independents or even Democrats may opt to have their say in the Republican caucus rather than participate in the Democratic process for Mr Biden beginning in March.

Ms Paine Caufield says she is keeping an eye on Democrats who are either frustrated with President Biden or concerned about another Trump candidacy coming to caucus with the conservative party.

“My guess is if we were to see an influx of independents and/or moderate Democrats participating in the Republican caucuses, my bet is that they vote for Nikki Haley. And so I think that potentially could push her up to outperform expectations,” she said.

Americans don't want, but are likely to get, a Biden-Trump rematch. What does that mean for democracy?

A December poll from the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research shows that broadly, Americans are not happy about the prospect of another face-off between President Biden and his predecessor.

Fifty-eight per cent would be “very” or “somewhat dissatisfied” with Mr Trump as the Republican nominee, while 56 per cent of US adults would be “very” or “somewhat” dissatisfied with Mr Biden as the Democratic presidential nominee in 2024.

This begs the question: What does this mean for American democracy, if a Biden-Trump rematch seems all but certain, and yet nobody seems very happy about it?

Ms Paine Caufield says that in this moment “political parties aren't very strong” in the US, and that the power to pick candidates has moved further away from political parties and more towards individual voters.

Voters, says Ms Paine Caufield, “can be fickle.”

“They can be taken in by a single personality, they are not always invested in the long-term development of the party … They're not always the best candidates.”

“When Donald Trump was originally nominated in 2016, the words everybody used was it was a hostile takeover of the Republican Party. I think it's proven to be exactly that. But a strong political party could have stopped that from happening,” she added.