This year’s Unesco World Heritage Committee is historic in many regards. Not only is it the first time the event has been held in Saudi Arabia, but it is the first full in-person meeting since 2020. It is also, curiously, the third time it has been held in the Gulf in a decade, with Qatar hosting in 2014 and Bahrain in 2018.

Sheikh Khalifa bin Ahmed Al Khalifa, president of the Bahrain Authority of Culture and Antiquities, was in Riyadh for the start of the event. In an exclusive with The National, he says “everyone is in high spirits to engage with such a heavy agenda”.

Pointing to the nominations from Saudi Arabia, Palestine and Tunisia, he adds: “It's always a privilege for us to see more Arab sites represented on this list.”

However, he says: “It’s important to note that the inscription process of new sites is just one part of the committee's agenda.

“It meets regularly as well to look into the state of conservation reports that are submitted periodically to ensure that the conservation measures are in place for the protection and preservation of these sites.”

The committee has also been discussing the sites already on the World Heritage List that are in danger. While Venice avoided being added to the list, Ukraine’s Kyiv and Lviv were added to it, due to the continuing war with Russia. Elsewhere, the site of the Tombs of the Buganda Kings in Kasubi, Uganda, was removed, following successful restoration work.

Sheikh Khalifa points out: “The Arab region has the highest percentage of sites in danger across the geographical compositions of Unesco. Some are due to armed conflict while others are due to human impact, development and so forth.”

Bahrain is home to the Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage, a Unesco Category 2 Centre, which works towards capacity building in the Arab world, and ensuring better representation on the World Heritage List.

“We don't directly interfere with the inscription process – what we do is we enable national experts in the Arab states to prepare nomination files. Because it’s easy to support a file, but it's more valuable to really invest in expertise.”

At the moment, among various projects, the Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage is working on encouraging trans-boundary nominations in the Arab region.

Sometimes, states jointly submit nominations for heritage that spans borders – especially when it comes to natural heritage. This year, Iran and Azerbeijan successfully submitted the trans-boundary Hyrcanian Forests. However, the Arab world currently does not have any such sites.

One strong contender could be the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route, which spans Saudi Arabia and Iraq, although this hasn’t yet been submitted for consideration.

Sheikh Khalifa stresses: “Managing plans across borders can be very challenging because of different regulations and different policies … In the past, we’ve seen sites with a weak nomination that don't end up on the list.”

This year, there were 50 proposed sites up for nomination to the list – including eight from the Mena, seven of which were successfully inscribed. However, on the heels of Unesco’s recent report, Operational Strategy for Priority Africa 2022-2029, much of the discussion so far has been centred on underrepresentation of African heritage sites.

Remarkably, Rwanda had its first World Heritage Site inscribed this year, followed by a second composed of a series of memorial sites of the Rwandan Genocide. Conflict sites are rarely inscribed, as the notion of conflict as heritage presents several difficult questions. Even in the cases of Hiroshima and Auschwitz, Sheikh Khalifa says “it was clear that these were done on an exceptional basis” rather than a precedent.

However, Sheikh Khalifa says over the past couple of years, there has been a drive to inscribe more African sites, even those that received a recommendation of deferral, due to further necessary revisions of approvals.

“But we need to also bear in mind that we need to ensure that the state party actually has the capacity to continue with the inscription process, because the inscription is the starting point, it is not an achievement.

“That inscription is a global recognition of the importance of that property. The state party will then have a responsibility as a signatory of that convention, to ensure that that site is protected for future generations.”

He adds: “There’s always this perception or terminology – ‘crowned’ – a site is ‘crowned’, as if it has reached the end of its journey, when it has not. It’s a recognition from the international community that you've done a great job in preparing a nomination and ensuring to the international committee that you have legislation to protect that site.”

However, from there, states must then submit regular reports, outlining the steps they have taken towards maintaining that site’s outstanding universal value.

To Sheikh Khalifa, that universality is essential: “All sites inscribed offer a different element of our shared heritage.” While many perceive the Unesco status as a “touristic tool”, he says the purpose of the convention “is to conserve first”. He adds: “It's actually a conservation tool that can be harnessed to different purposes, including tourism, social development, biodiversity conservation.”

However, successfully maintaining those commitments can be a very difficult feat. In Africa, for example, Sheikh Khalifa points out that many architectural sites are based on wood or other organic materials, which require enhanced levels of conservation interventions. “And those materials are prone to fires, and other disturbances that other materials might not be.”

One of the biggest talking points in the build-up to Cop28 is the impact of climate change on World Heritage Sites. The UAE’s Minister of Culture Salem Al Qassimi has stressed the need for global partners to collaborate to address climate challenges through culture and creativity.

Sheikh Khalifa echoes this sentiment, as climate change presents states with a variable that in many respects lies beyond their control. If a development such as a dam poses a threat to a site, for example, the state party can decide whether to approve or stop such a project. He explains. “But when it comes to climate change, can the state party slow down the process individually as it pertains to that particular site?”

Having participated in a number of working groups focused on climate change policy, Sheikh Khalifa remarks: “And I don't think we should perceive as climate change just in terms of impacts. We need to explore how World Heritage Sites can assist us in coping with climate change. Many of these world heritage sites are carbon sinks; many of them are rainforests; many of them are ecosystem regulators. So how do we harness World Heritage Sites in terms of our mitigation and adaptation measures?

“How do we use them to enable communities that rely on them to cope with the challenges of climate change?”

Climate change also presents another curious dimension, which is the challenge between development and conservation. Sheikh Khalifa pointed to an event that took place on the sidelines of the of the World Heritage Committee focused on the heritage impact assessments of renewable energy projects.

“On one hand, you want more wind farms, you want more solar panels, you want all of the other forms of renewable energy. But in many cases, those renewable energy projects are in conflict with the heritage values of specific sites. So you may have windmills for example, that will ruin the visual integrity of the landscape. Or you would have dams, which, although arguably are a renewable source of energy, have devastating impacts on certain ecosystems.”

These are just some of the challenges facing sites across the world. Others, he says, are more location specific. He explains: “In certain cases, including, for example, the rock art sites in Algeria, it's such a remote area that you will never be able to keep an eye on the site for 24 hours a day … When you're talking about the Great Barrier Reef, it's the size of Western Europe as a single World Heritage Site. So, I think scale also provides another layer of a challenge that many other countries face.”

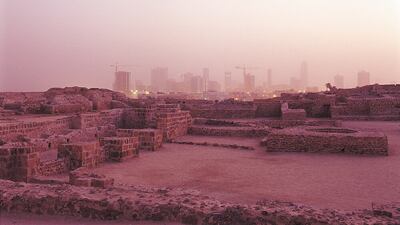

It is not, however, an issue Bahrain faces. Spanning just 786.5 square kilometres, the country has a very high concentration of World Heritage Sites, with a total of three – which Sheikh Khalifa says are “embedded within our urban fabric and social fabric”.

“There are very few cities or countries I can think of where you can visit three World Heritage Sites in one day. Bahrain is one of them. You can spend the morning in one site, the afternoon at a second and you can spend the evening at the third site, and it will be a very comfortable day."