Ask your average anglophone reader to name an Azerbaijani writer and there is a good chance they will draw a blank. Kurban Said doesn't count because the name that adorns the jacket of Ali and Nino, the spellbinding romance commonly regarded as Azerbaijan's national novel, is a pseudonym. Some claim the true identity of the author might even have been an Austrian baroness.

If there's any justice, then the first English publication of Days in the Caucasus will raise the profile of a bona fide Azerbaijani author who went by the name of Banine. This book, a captivating memoir of her childhood and early teenage years in her home country, was originally published in French in 1945. Anne Thompson-Ahmadova's seamless translation into English introduces us to a unique narrative voice and immerses us in an opulent world that has since vanished.

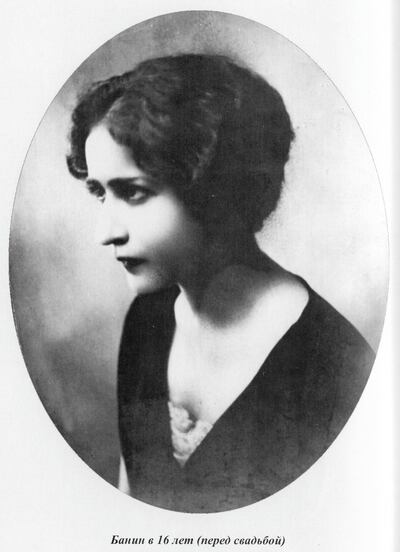

Banine's real name was Ummulbanu Asadullayeva. She was born in 1905, a year she describes as "full of strikes, pogroms, massacres and other displays of human genius". Maintaining this sardonic tone, she claims to have added to the chaos and bloodshed "since I killed my mother as I came into the world". She grew up in a family that had become incredibly wealthy through the discovery and sale of oil, but as her father was often away on business, Banine and her siblings were frequently left in the care of a German governess.

The whole family would spend half the year in Baku and in spring, before the city became dusty and stifling. The family, their relatives and an entourage of domestic staff – "the population of a small village" – retreated to a country estate. Banine recalls long days of hammam parties, storytelling, trips to the Caspian Sea – and playing at "killing Armenians" with her boisterous cousins, Asad and Ali.

Now and again, clouds gather over the family. There is a protracted fiery feud over a grandfather's inheritance. Banine's pangs of young love ("this celebrated malaise") for a family gardener, a Georgian prince and an officer result in disappointment. Her eldest sister Leyla elopes with a suitor, which the family refers to as "the Great Shame" and they discuss it "in the same way they talked of an earthquake or a great plague". Her father remarries, but his glamorous, cosmopolitan wife detests backwater Baku and is indifferent towards Banine.

Soon enough, Banine's life is engulfed by more turbulence. The Russian Revolution erupts and she is cooped up indoors for two weeks while violence breaks out on the streets. Peace is restored briefly and Azerbaijan declares independence from Russia, but soon the Red Army rolls into town and reclaims the errant country.

The second half of the book comprises a dramatic change in fortunes. With the Russian Empire now solidly Soviet, the family is stripped of their wealth. Some members flee to France, but Banine's father is jailed. The Baku house is deemed too large for Banine's family and a commissar, his wife and their staff move in; the country house is similarly carved up, its rooms requisitioned for a holiday camp for revolutionary veterans.

Two remarkable events end this phase of Banine's life, paving the way for a new start. At 15, she marries Jamil, a man 20 years older than her. She loathes him. In 1924, she finds a means of escaping both her husband and her homeland. In Constantinople, Banine bids him farewell and boards the Orient Express, which is bound for the city of her dreams, Paris.

As a narrator, Banine is appealingly candid and refreshingly self-effacing, quick to mock her "odd, rich, exotic" family, her benighted compatriots, and her own appearance, sentiments and allegiances.

Days in the Caucasus is an unalloyed delight. As a narrator, Banine is appealingly candid and refreshingly self-effacing, quick to mock her "odd, rich, exotic" family, her benighted compatriots, and her own appearance, sentiments and allegiances. Many of her recollections are presented as wry observations, such as "our meals were poor in provender but rich in sighs and tears". Other moments are also funny, not least when some relatives are searched by militiamen in a botched bid for freedom. "There were jewels in my aunt's hair, in the children's mouths, in the hems of their clothing."

Other than Banine, two characters light up the page: her eccentric uncle, who offers philosophical wisdom and pilfers ashtrays and cutlery from hotels, and her formidable grandmother, an "excessively fanatical" Muslim with a foul mouth and penchant for poker.

This is a vivid coming-of-age story that also provides a valuable glimpse of a life lived in a half-Islamic, half-western world at a pivotal moment in history. Banine wrote a sequel called Days in Paris. If there is as much wit, charm and insight in that book as there is in this one, we can only hope it will also be translated into English soon.

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EClara%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2019%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EPatrick%20Rogers%2C%20Lee%20McMahon%2C%20Arthur%20Guest%2C%20Ahmed%20Arif%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDubai%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EIndustry%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ELegalTech%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFunding%20size%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20%244%20million%20of%20seed%20financing%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EWamda%20Capital%2C%20Shorooq%20Partners%2C%20Techstars%2C%20500%20Global%2C%20OTF%2C%20Venture%20Souq%2C%20Knuru%20Capital%2C%20Plug%20and%20Play%20and%20The%20LegalTech%20Fund%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

What are the influencer academy modules?

- Mastery of audio-visual content creation.

- Cinematography, shots and movement.

- All aspects of post-production.

- Emerging technologies and VFX with AI and CGI.

- Understanding of marketing objectives and audience engagement.

- Tourism industry knowledge.

- Professional ethics.

UAE SQUAD

Ahmed Raza (Captain), Rohan Mustafa, Jonathan Figy, CP Rizwan, Junaid Siddique, Mohammad Usman, Basil Hameed, Zawar Farid, Vriitya Aravind (WK), Waheed Ahmed, Karthik Meiyappan, Zahoor Khan, Darius D'Silva, Chirag Suri

Company profile

Name: Tharb

Started: December 2016

Founder: Eisa Alsubousi

Based: Abu Dhabi

Sector: Luxury leather goods

Initial investment: Dh150,000 from personal savings

What should do investors do now?

What does the S&P 500's new all-time high mean for the average investor?

Should I be euphoric?

No. It's fine to be pleased about hearty returns on your investments. But it's not a good idea to tie your emotions closely to the ups and downs of the stock market. You'll get tired fast. This market moment comes on the heels of last year's nosedive. And it's not the first or last time the stock market will make a dramatic move.

So what happened?

It's more about what happened last year. Many of the concerns that triggered that plunge towards the end of last have largely been quelled. The US and China are slowly moving toward a trade agreement. The Federal Reserve has indicated it likely will not raise rates at all in 2019 after seven recent increases. And those changes, along with some strong earnings reports and broader healthy economic indicators, have fueled some optimism in stock markets.

"The panic in the fourth quarter was based mostly on fears," says Brent Schutte, chief investment strategist for Northwestern Mutual Wealth Management Company. "The fundamentals have mostly held up, while the fears have gone away and the fears were based mostly on emotion."

Should I buy? Should I sell?

Maybe. It depends on what your long-term investment plan is. The best advice is usually the same no matter the day — determine your financial goals, make a plan to reach them and stick to it.

"I would encourage (investors) not to overreact to highs, just as I would encourage them not to overreact to the lows of December," Mr Schutte says.

All the same, there are some situations in which you should consider taking action. If you think you can't live through another low like last year, the time to get out is now. If the balance of assets in your portfolio is out of whack thanks to the rise of the stock market, make adjustments. And if you need your money in the next five to 10 years, it shouldn't be in stocks anyhow. But for most people, it's also a good time to just leave things be.

Resist the urge to abandon the diversification of your portfolio, Mr Schutte cautions. It may be tempting to shed other investments that aren't performing as well, such as some international stocks, but diversification is designed to help steady your performance over time.

Will the rally last?

No one knows for sure. But David Bailin, chief investment officer at Citi Private Bank, expects the US market could move up 5 per cent to 7 per cent more over the next nine to 12 months, provided the Fed doesn't raise rates and earnings growth exceeds current expectations. We are in a late cycle market, a period when US equities have historically done very well, but volatility also rises, he says.

"This phase can last six months to several years, but it's important clients remain invested and not try to prematurely position for a contraction of the market," Mr Bailin says. "Doing so would risk missing out on important portfolio returns."

More from Neighbourhood Watch:

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

KILLING OF QASSEM SULEIMANI

Skewed figures

In the village of Mevagissey in southwest England the housing stock has doubled in the last century while the number of residents is half the historic high. The village's Neighbourhood Development Plan states that 26% of homes are holiday retreats. Prices are high, averaging around £300,000, £50,000 more than the Cornish average of £250,000. The local average wage is £15,458.

How to wear a kandura

Dos

- Wear the right fabric for the right season and occasion

- Always ask for the dress code if you don’t know

- Wear a white kandura, white ghutra / shemagh (headwear) and black shoes for work

- Wear 100 per cent cotton under the kandura as most fabrics are polyester

Don’ts

- Wear hamdania for work, always wear a ghutra and agal

- Buy a kandura only based on how it feels; ask questions about the fabric and understand what you are buying

How to protect yourself when air quality drops

Install an air filter in your home.

Close your windows and turn on the AC.

Shower or bath after being outside.

Wear a face mask.

Stay indoors when conditions are particularly poor.

If driving, turn your engine off when stationary.

ELIO

Starring: Yonas Kibreab, Zoe Saldana, Brad Garrett

Directors: Madeline Sharafian, Domee Shi, Adrian Molina

Rating: 4/5

The specs: 2018 Opel Mokka X

Price, as tested: Dh84,000

Engine: 1.4L, four-cylinder turbo

Transmission: Six-speed auto

Power: 142hp at 4,900rpm

Torque: 200Nm at 1,850rpm

Fuel economy, combined: 6.5L / 100km

Brief scores:

Day 2

England: 277 & 19-0

West Indies: 154

So what is Spicy Chickenjoy?

Just as McDonald’s has the Big Mac, Jollibee has Spicy Chickenjoy – a piece of fried chicken that’s crispy and spicy on the outside and comes with a side of spaghetti, all covered in tomato sauce and topped with sausage slices and ground beef. It sounds like a recipe that a child would come up with, but perhaps that’s the point – a flavourbomb combination of cheap comfort foods. Chickenjoy is Jollibee’s best-selling product in every country in which it has a presence.

Marathon results

Men:

1. Titus Ekiru(KEN) 2:06:13

2. Alphonce Simbu(TAN) 2:07:50

3. Reuben Kipyego(KEN) 2:08:25

4. Abel Kirui(KEN) 2:08:46

5. Felix Kemutai(KEN) 2:10:48

Women:

1. Judith Korir(KEN) 2:22:30

2. Eunice Chumba(BHR) 2:26:01

3. Immaculate Chemutai(UGA) 2:28:30

4. Abebech Bekele(ETH) 2:29:43

5. Aleksandra Morozova(RUS) 2:33:01

The specs

Engine: 3.0-litre six-cylinder turbo

Power: 398hp from 5,250rpm

Torque: 580Nm at 1,900-4,800rpm

Transmission: Eight-speed auto

Fuel economy, combined: 6.5L/100km

On sale: December

Price: From Dh330,000 (estimate)

The%20specs

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%203.0-litre%20six-cylinder%20turbo%20(BMW%20B58)%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20340hp%20at%206%2C500rpm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20500Nm%20from%201%2C600-4%2C500rpm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20ZF%208-speed%20auto%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3E0-100kph%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204.2sec%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETop%20speed%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20267kph%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EOn%20sale%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Now%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20From%20Dh462%2C189%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EWarranty%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2030-month%2F48%2C000k%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

U19 WORLD CUP, WEST INDIES

UAE group fixtures (all in St Kitts)

Saturday 15 January: v Canada

Thursday 20 January: v England

Saturday 22 January: v Bangladesh

UAE squad

Alishan Sharafu (captain), Shival Bawa, Jash Giyanani, Sailles Jaishankar, Nilansh Keswani, Aayan Khan, Punya Mehra, Ali Naseer, Ronak Panoly, Dhruv Parashar, Vinayak Raghavan, Soorya Sathish, Aryansh Sharma, Adithya Shetty, Kai Smith

CHINESE GRAND PRIX STARTING GRID

1st row

Sebastian Vettel (Ferrari)

Kimi Raikkonen (Ferrari)

2nd row

Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes-GP)

Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes-GP)

3rd row

Max Verstappen (Red Bull Racing)

Daniel Ricciardo (Red Bull Racing)

4th row

Nico Hulkenberg (Renault)

Sergio Perez (Force India)

5th row

Carlos Sainz Jr (Renault)

Romain Grosjean (Haas)

6th row

Kevin Magnussen (Haas)

Esteban Ocon (Force India)

7th row

Fernando Alonso (McLaren)

Stoffel Vandoorne (McLaren)

8th row

Brendon Hartley (Toro Rosso)

Sergey Sirotkin (Williams)

9th row

Pierre Gasly (Toro Rosso)

Lance Stroll (Williams)

10th row

Charles Leclerc (Sauber)

arcus Ericsson (Sauber)

A%20Little%20to%20the%20Left

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDeveloper%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EMax%20Inferno%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EConsoles%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20PC%2C%20Mac%2C%20Nintendo%20Switch%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E4%2F5%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Results

5pm: Wadi Nagab – Maiden (PA) Dh80,000 (Turf) 1,200m; Winner: Al Falaq, Antonio Fresu (jockey), Ahmed Al Shemaili (trainer)

5.30pm: Wadi Sidr – Handicap (PA) Dh80,000 (T) 1,200m; Winner: AF Majalis, Tadhg O’Shea, Ernst Oertel

6pm: Wathba Stallions Cup – Handicap (PA) Dh70,000 (T) 2,200m; Winner: AF Fakhama, Fernando Jara, Mohamed Daggash

6.30pm: Wadi Shees – Handicap (PA) Dh80,000 (T) 2,200m; Winner: Mutaqadim, Antonio Fresu, Ibrahim Al Hadhrami

7pm: Arabian Triple Crown Round-1 – Listed (PA) Dh230,000 (T) 1,600m; Winner: Bahar Muscat, Antonio Fresu, Ibrahim Al Hadhrami

7.30pm: Wadi Tayyibah – Maiden (TB) Dh80,000 (T) 1,600m; Winner: Poster Paint, Patrick Cosgrave, Bhupat Seemar

Australia tour of Pakistan

March 4-8: First Test, Rawalpindi

March 12-16: Second Test, Karachi

March 21-25: Third Test, Lahore

March 29: First ODI, Rawalpindi

March 31: Second ODI, Rawalpindi

April 2: Third ODI, Rawalpindi

April 5: T20I, Rawalpindi

WHAT%20MACRO%20FACTORS%20ARE%20IMPACTING%20META%20TECH%20MARKETS%3F

%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Looming%20global%20slowdown%20and%20recession%20in%20key%20economies%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Russia-Ukraine%20war%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Interest%20rate%20hikes%20and%20the%20rising%20cost%20of%20debt%20servicing%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Oil%20price%20volatility%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Persisting%20inflationary%20pressures%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Exchange%20rate%20fluctuations%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Shortage%20of%20labour%2Fskills%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20A%20resurgence%20of%20Covid%3F%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Electric scooters: some rules to remember

- Riders must be 14-years-old or over

- Wear a protective helmet

- Park the electric scooter in designated parking lots (if any)

- Do not leave electric scooter in locations that obstruct traffic or pedestrians

- Solo riders only, no passengers allowed

- Do not drive outside designated lanes

FIXTURES (all times UAE)

Sunday

Brescia v Lazio (3.30pm)

SPAL v Verona (6pm)

Genoa v Sassuolo (9pm)

AS Roma v Torino (11.45pm)

Monday

Bologna v Fiorentina (3.30pm)

AC Milan v Sampdoria (6pm)

Juventus v Cagliari (6pm)

Atalanta v Parma (6pm)

Lecce v Udinese (9pm)

Napoli v Inter Milan (11.45pm)

About RuPay

A homegrown card payment scheme launched by the National Payments Corporation of India and backed by the Reserve Bank of India, the country’s central bank

RuPay process payments between banks and merchants for purchases made with credit or debit cards

It has grown rapidly in India and competes with global payment network firms like MasterCard and Visa.

In India, it can be used at ATMs, for online payments and variations of the card can be used to pay for bus, metro charges, road toll payments

The name blends two words rupee and payment

Some advantages of the network include lower processing fees and transaction costs