From the glamour suggested by two almost empty bottles of bright Revlon nail polish to a tiny hammer and sickle stitched in red on a custom-made corset, a series of photographs on display this week at the Michael Hoppen Gallery in London hint at the carefully constructed public identity and exuberant inner life of the artist Frida Kahlo.

Kahlo died in 1954 and her personal possessions remained locked in darkness, in the bathroom of the home in Mexico City that she shared with her husband, the painter Diego Rivera. Rivera commanded that the room remain sealed until 15 years after his own death, which occurred in 1957, but it was not until 2004, almost 50 years later, that the Museo Frida Kahlo decided to catalogue its contents.

The Japanese photographer Ishiuchi Miyako was invited to travel to Mexico, a country entirely unfamiliar to her, to photograph more than 300 relics from Kahlo’s life. It was to be an extraordinary project that fostered a surprising intimacy between the subject and the woman behind the lens, as the gallery owner explained in an interview with the BBC this week.

“I said to Ishiuchi, it’s like standing in a room and listening to a conversation between both of you because you are not simply recording what she wore, you are highlighting her character. And in that sense that conversation is fascinating. It’s all the things you want to hear are somehow brought to the fore,” Michael Hoppen says.

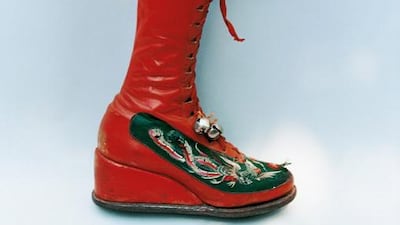

Invalided by polio as a child and a near-fatal accident at 18 when a bus she was riding was hit by a tram, Kahlo had to wear a corset to support her body, and much later a prosthesis after her leg was amputated in 1953.

Kahlo chose the traditional Tehuana dresses that Miyako photographed to assert a cultural sense of belonging but, perhaps, just as importantly for a female artist whose name became synonymous with the self-portrait, they concealed her physical imperfections. And all this at a time when bleached and stylised Hollywood actresses were the feminine ideal of beauty.

The extraordinary reds, yellows and turquoises that leap out from Miyako’s prints convey Kahlo’s equally vivid and undeniable presence just as the bells on the laces of her prosthetic leg made sure you could hear the artist coming.

As Hoppen puts it: “Kahlo swam against the tide almost every day. And she won. She was a true original.”

• Frida by Ishiuchi Miyako (2013) is being shown at the Michael Hoppen Gallery in London until July 12. For all enquiries, visit www.michaelhoppengallery.com.