Appropriately for an author who writes a book a month, Terry Deary is hard at work on the day we speak. "I'm just writing about [theologian and initiator of the Protestant Reformation] Martin Luther," he says, "who didn't nail a proclamation to a church door as everyone thinks." He didn't? "No! It sounds good, doesn't it? All very dramatic. But it's just a fairy story." The Luther tale will form a chapter in a new book in Deary's Horrible Histories series called Horrible Events. "When Luther split the Catholic church, it caused some of the most horrible history ever," he explains.

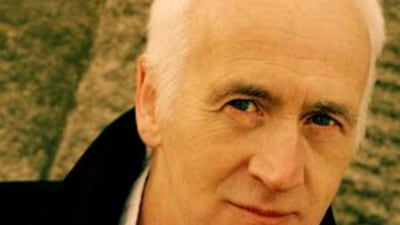

So friendly and approachable is Deary, it's easy to forget his grand status as the world's best-selling author of children's non-fiction. Since his first Horrible Histories titles, Awesome Egyptians and Terrible Tudors, came out in 1993, the 64-year-old has sold over 20 million books worldwide and has seen the brand he created expand to accommodate a mass of multimedia tie-ins. There are Wii games and board games, Top Trumps cards and museum exhibitions like Terrible Trenches, currently running at London's Imperial War Museum. The Horrible Histories TV series has just been nominated for a Bafta award. And of course there are the hugely successful shows produced by Birmingham Stage Company, a double bill of which, Frightful First World War & Woeful Second World War - Blitzed Brits, comes to Dubai Community Theatre and Arts Centre on December 12.

The First World War show is adapted from the Horrible Histories non-fiction book of the same name. But the Second World War show is based on a Horrible Histories novel. "That one's very much my narrative," says Deary. "It's about two children who are evacuated from Coventry. I'm quite keen for people to understand that the Blitz wasn't all about London." Perhaps surprisingly, Deary admits he's never seen the shows. "I have script approval. That's all I have time for because I'm too busy. But the director, Phil Clark, is someone I've known for 35 years, since I was an actor myself in Brecon in Wales. He was a sixth-former at a local school who came and tagged along with the company. He helped to mend the costumes and put up the sets and went on to have a career in theatre."

With their playful focus on beheadings, plagues and foul-smelling sewers, Deary's books celebrate what's grisly and ghoulish about the past. His main goal, plainly, is to make history fun. But he's also challenging the idea that it's a subject best taught from an Olympian, omniscient viewpoint. By focusing on the humdrum details of ordinary people's lives, Deary encourages empathy and identification in his young readers.

"Why do people behave the way they do? When you understand that then the world becomes a better place. I'm not a historian, I'm a children's author, and that's why my books are so successful. I don't say: 'Sit down and listen, I know all this and I'm going to tell you'. I say: 'You'll never guess what I've found out about this-'" That his books are used so widely in schools enrages Deary, an anarchist at heart who once refused to meet the Queen of England and didn't bother to reply to an invitation from Tony Blair to visit Downing Street.

"I'm anti-authority, anti-establishment, anti-school. It frustrates me when teachers come along and use my books to liven up their deadly dull lessons. I wish there was some way I could sue them. "About 20 years ago when they were devising the UK's National Curriculum, a politician said to me, 'All that matters in history teaching is facts, facts, facts' - unaware that that's exactly what Mr Gradgrind says in Hard Times! Charles Dickens was parodying that attitude 150 years ago!"

Boys, especially, love Deary's books, though he insists his readership is not as polarised along gender lines as people think; that the ratio is more like 60:40 than 70:30. Educationalists often bemoan boys' lack of enthusiasm for reading. Deary argues that schools' insistence on teaching reading using fiction excludes boys, many of whom find fiction boring. "People come up to me and say: 'My son wouldn't read a book until he picked up yours.' That's because, as all the research suggests, boys learn to read better with non-fiction. They prefer it. Teachers know this but they're too stupid to do anything about it." Ouch!

Deary grew up in a working-class household in Sunderland in the north-east of England and still lives in the area. "I didn't read as a child. We were too poor to have books. The schools weren't interested. They just crammed us for the 11-plus [examinations to get into grammar schools] and when the exams were over there was a hiatus during which the teacher read aloud to us from John Buchan's The 39 Steps - this racist, xenophobic novel! You know, 'If you're German, you're evil'. Completely inappropriate."

Deary was bright and got into grammar school - a significant achievement. But he did not enjoy the experience: "They made us read books like Thomas Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles which I didn't understand." He left with nine O Levels and three A Levels (again, a significant achievement) and got a job with the local electricity board before moving into acting. From there he drifted into teaching drama, and from there into writing. His first children's book, the novel The Custard Kid, was published in 1976.

"A lot of people forget I write fiction too," Deary points out, and he's right. (Check out his Master Crooks Crime Academy and Time Detectives series - they're great fun.) Did his success take him by surprise? "The success of Horrible Histories did, certainly. I'd written about 50 books before that and I was plodding along. Writing children's books is so badly paid for the most part - the average children's author earns around £4,000 [Dh24,000] a year - but the success of Horrible Histories allowed me to give up the day job."

He has been known to write 8,000 words a day. "A lot of writers whinge. If writing is hard work, you're doing something wrong. I was born to be a writer. If you don't like writing then maybe you should try something else, like digging coal." The only downside to success is that it can be a distraction. "Yesterday I wrote about 100 words when I should have written 2,000 because I was dealing with a TV company who were making a programme about a Viking festival in York," Deary says. "They want me to appear at it, so I had to get my publisher to make sure there were books up there to be sold and get the TV company which makes Horrible Histories to edit extracts which could be shown at the event. It took me all day, but I'm not complaining. There are far worse ways to earn a living."

Compare Deary to his writer peers JK Rowling and Philip Pullman and it's a surprise in some ways that his profile isn't as high. Perhaps it is because he guards his privacy so fiercely. He never allows journalists to interview him at his house and does relatively few public events. "I don't publicise myself. I sit in my study and write books. I do the odd interview. Last week I was at the Bafta Awards with all the luvvies. I'm a children's author and I don't believe that being a children's author makes me special. It's just a job that I'm quite successful at. I don't like celebrity treatment."

Deary works closely with his publishers to identify topics that might make for good books. Then professional researchers supply him with material which he shapes in his unique, patented way. He doesn't want a mass of material - "If I did I'd just go to a library or print it off the internet" - and it has to be pithy and relevant and full of "little gems". The tone of the Horrible Histories books concerned with recent conflicts is less antic and more respectful of those who lived through those times than, say, Terrible Tudors. There are jokes, but they tend to be from the period.

"That's how people got through it," says Deary. "They made up jokes and silly songs to endure the hell they were facing. "Besides, Horrible Histories aren't always funny. I remember having a meeting with the TV company who were adapting the Second World War book and we got to the page about the Holocaust and the producers looked at each other and said: 'Well of course, we can't put the Holocaust in.' I thought that was good, that there was something a book could do that TV couldn't."

Deary gets thousands of e-mails from his young fans and tries to answer them all. (E-mails from teachers are auto-deleted.) The variety of responses to his books amazes him. "There's no such thing as a child, just an individual. I got an e-mail recently from the parents of a little girl which said: 'Our daughter is having nightmares that the world is going to end in 2012 because of a remark you made in your Aztecs book [Angry Aztecs].' I said: 'Well, she's the only one. And anyway, there's a massive film about the world ending in 2012 about to come out! You can't blame it on me.'

"That child had a particular problem, though of course I couldn't say that to the parents. All children react differently. Some children will think killing a hamster and eating it is worse than chopping someone's head off. All I can do is present the facts and say: This is the world we live in, be careful." Frightful First World War & Woeful Second World War - Blitzed Brits, plays at Dubai Community Theate and Arts Centre from December 12. For information visit www.ductac.org