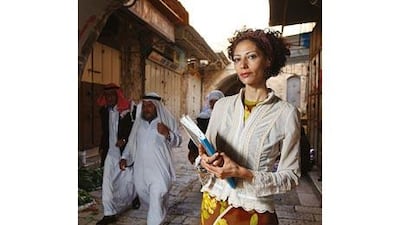

On a cool, cusp-of-summer night, an expectant crowd streams into an enchanting Ottoman-era castle at a village near Nablus. The grandly arched Al Qasim Palace, renovated a few years ago, is one of the venues for PalFest - an annual literary festival across the occupied West Bank. For the audience which has turned out for this evening of poetry, it's a sorely needed cultural event. The very existence of a Palestinian literary festival confronting "the culture of power with the power of culture" elicits full-beam support. They've come to applaud the local Palestinian poets and performers featured in the line-up. But most of all they have come to see Suheir Hammad. This 36-year-old Palestinian-American is fast developing a global fan base for her poems, spoken word performances and acting debut in Annemarie Jacir's acclaimed 2008 film, Salt Of This Sea. Hammad, a self-defined artist, activist and poet, was virtually playing herself in the award-winning film that tells the story of an American woman returning to what is now Israel, decades after her Palestinian family's eviction in the 1948 war. It is a road trip of self-discovery for her character, and Hammad keeps the drama rolling with an easily convincing screen persona. The same themes - Palestinian exile and return; refugee status and statelessness - are the basis of her work as a poet and spoken word artist: driving the syntax, filling out the vowels, pumping a resilient energy into the rhymes. Her poem, First Writing Since, composed in the aftermath of 9/11, was full of compassion, both for the victims of the attack and for the people on whom revenge would be exacted. Those stirring, electric words raced around the world and caught the attention of the American hip-hop entrepreneur, Russell Simmons, who instantly put Hammad on HBO's Def Poetry programme, a showcase for live performance poets. Since then, she has travelled widely with her poetry, making radio and TV appearances and performing her work at universities, prisons and on street corners. She has released numerous anthologies and, acclaimed as a "new voice with an authentic blend of language", is the most visible Palestinian in American artistic circles. "I couldn't have been anything else," she says when we meet in Palestinian East Jerusalem, at the end of a busy, week-long tour of workshops and performances across the West Bank. "I committed myself very early on to poetry." Hammad was born in Amman, Jordan, to parents who had fled their homes in Lydda and Ramla - now Lod and Ramle, and both in Israel. "My mum always tells me to make sure to say I was born in a hospital," she says smiling. "It meant a lot in those days, as an 'official refugee', whatever that means." Hammad spent her fourth year in Beirut, in the midst of civil war, before her family moved to the United States, settling first in Brooklyn and then moving to Staten Island. "In a way, my family's life is a microcosm of a larger Palestinian experience," she says. "For all our spectrum of humanity, which is as wide as any other people's, we have this shared sense of movement, persistent movement, in the past few decades." The constant relocation is today described by Hammad - the eldest of five - as reflecting the fortitude of her refugee parents; their capacity to adapt, while hanging on to their culture. "They just made their way, having babies, feeding them, going from one ID to another," she says. "And to me that's poetry ? the fact that they got through a life I couldn't have imagined - they gifted me poetry." The multiple moves also exposed her to myriad cultures - a tangible influence on her spoken word style. "I grew up with hip-hop music," she says of her formative years in the migrant communities of Brooklyn. "First of all, it takes the profane - which is the American enslaved experience - and makes it cool and stylish. It is about knowing there is nothing to be done about racism and powerlessness and oppression, so you kind of make it your swagger. That's part of hip-hop, and I completely related to it." Hammad fuses both the attitude and the structures of hip hop with the rhythms that she knows from home - of the Arabic language, of Palestinian nationalist poetry and of the legends of Middle Eastern music - so that the word chains of her poetry often hammer out the tenets of another people's struggle.

"My parents were the first generation born into a deep failure - the failure of Israeli humanity, the failure of Arab nationalism," she says. "They were always playing their cassette music, so I heard [the Egyptian diva Umm Kalsoum's] Lissa Fikir every day. I didn't know any other Americans who listened to the same song on the way to work, while they were doing the dishes - and allowed themselves to cry. So I had a fascination for this music and language."

Religion is another cultural influence. The Quran is an inspirational thread that colours her distinctive narrative style. "I always go back to the Quran as this divine word with the mystery of sounds and mathematics. You know how the suras get bigger and then small, and I was always like, 'This whole verse is just the letter M; what could that possibly mean?' That's a poet kid's question. I was always interested in the texts and the music."

Hammad first visited Israel and the occupied Palestinian Territories when she was 25. "It was Israel's 50th anniversary and I wanted to know what it was like to be a half a lifetime of something," she says. "And everything in me compelled me to come back. My whole life, I had never been fully accepted as an American, and I hadn't really understood anything about being from here." But she stresses that things were completely different back then, during the years of the Oslo peace process, when Israelis would regularly take trips to the Palestinian West Bank, and a few of her Palestinian friends had boyfriends who were Israeli soldiers. "Israeli soldiers!" she exclaims. "I had no idea that small level of freedom and communication was going to end."

After that first trip, she began to cement the facts of her own family history. "My entire life I was told that my parents were evacuated, that their homes were taken over," she says. But there was no external confirmation of that story - not until the early 1990s, when Israel's "new historians" such as Benny Morris revealed some murky facts of the dawn of the country. Among the details that came out was Operation Dalet, a plan devised by Jewish defence forces in 1947, with the intention of clearing what they deemed to be hostile forces (Palestinians) from areas intended for the new Israel - effectively a green light for forced expulsion. "I had no idea, before Benny Morris uncovered it. Because their narrative had been erased or corrupted, it never seemed possible that what my parents said was true. And then there it all was - my family's story, in Operation Dalet. I didn't have that information until I was 30 years old."

Now, having visited the region every year for the past four years, Hammad is acutely aware of the corrosive effect of the concrete and steel separation barrier that Israel began building in 2002, and which encroaches on Palestinian land for much of its 703km length. "As foreigners and visitors, it doesn't really imprint on your mind, but as a poet you sit back and you think, well that is a child's horizon," she says. "There are places not far from where we are sitting where children don't see the sunrise because that wall is 7.5m high. So this week I have been thinking about how to feed imagination without a sunrise." Travelling across the West Bank for various stops on the PalFest circuit, Hammad knows first-hand how the checkpoints, barriers and the Israeli permits regime can choke Palestinian movement. "I heard that many American Jews and Israelis feel comfortable coming to my readings [in Palestinian East Jerusalem and the West Bank] and I'm happy for that. But when I speak with them, I always remind them of how hard it was for the [Palestinian] person sitting next to them to get there - and how much that changes the experience of coming to a poetry evening, having to go through a two-week permit obligation and four hours at a checkpoint to go home. And, in a way, I don't want to be the one to say that to people. It's not my job, you know. I'm not everyone's older sister."

One area where Hammad does embrace sisterhood is as a feminist, but she thinks feminism has an entrenched difficulty with Muslim women, and they with it. "Because so much of feminism has come from the West, we have had issues with claiming it, because of the absences in it - the lack of a sense of spirituality, a sense of family, a sense of being a woman in a community." Hammad wants to bring nuance to the western notion of female empowerment. "If anything, women who consider themselves traditional feminists have more of a problem with, or are more ignorant about, the east and Islam. If you study the history of it, you can see why," she says, explaining that early feminism had its roots in a world that simply didn't see Muslim women. None of that lessens the surprise she feels at the common western view of Muslim women. "I walk into a university here and 97 per cent of the women are covered in a new way, in all these different styles." She says when she sees young Muslim women "negotiate all the time, negotiate for a million things", she wants to ask westerners in what way they are disempowered. Feminism has taught her "to ask women how they feel about who they are and what they look like and how they move in the world".

Meanwhile, her onscreen success in Salt Of The Sea has equipped her with another - and unexpected - platform. "I wouldn't have done any other movie. I have never been interested in acting and wouldn't say that I'm an actor." The first feature-length film directed by a Palestinian woman, it was shot on location in Ramallah and Jaffa. "It was surreal for me. I've never been trained in acting, but I'd gone through that checkpoint to get to Ramallah so many times in my life and I've been asked those questions so many times. I've even used those same lines: 'I'm an American!', 'Is there something wrong with my visa?' So shooting it, I was completely there." Hammad relates how, when Salt Of This Sea was screened in the US, audiences enthused about the sisterly solidarity of her friendship with the film's Israeli producer. But she wouldn't let them gush for too long. "She basically sponsored my entire trip," says Hammad of the producer. "She had to give her ID number and promise that I would never marry here ? I just remind people how humiliating this is for both of us, to have this unequal power dynamic; that we could never be true friends if she has to go out of her way to vouch for me in that way. That's not a real connection." Hammad has a natural wordsmith's enjoyment of language flow, play and pattern, but she insists she is not a natural performer. "When people talk about presence, I really don't feel that. In my mind I'm thinking a million other things, like did I mess up? Or is my voice OK? Do I project back over there? And can I please ignore that man in the audience who is talking on the phone? And that woman doesn't hate me, she just looks like that."

Her sense of being grounded, in control, comes from a different source. "If you are not a natural performer and you don't get fed on the performance - which I do not - you find a way to be outside of your body and make it about the bigger intention," she says. One crucial factor is what she projects to the younger generation of Palestinians - future artists, poets and performers. "When I was growing up, I never looked up and saw a woman who looked like me, spoke for me. And any time I could point to a woman who had become a success, she was always sexually available in her dress and her art." Now, she considers her potential as a role model to be part of a careful remit. "It's something I hold as a dear responsibility. I know that the girls coming after me, their parents will use me either to benefit them or to hinder them. I can't control that, but I can be aware of it." As much as Hammad inspires generations of Palestinians, they are equally a source of strength and inspiration for her. "Because that is all there is, there is no other power. It can all be taken away. A lot of the writers with PalFest have talked about the privilege of our imagination. If we want a safer, better, fairer world, we have to feed children's imaginations - and we are not always going to like what they come up with."