One of John Elliott's enduring memories of working on the town plans of Abu Dhabi is from a day in 1967, the year he arrived in the UAE.

He and Sheikh Zayed - along wth four soldiers - were in a Land Rover. The Sheikh wanted to map out where the so-called national houses would go, homes that would be built and given to locals.

"I want the houses to go from here," he told Elliott, and instructed one soldier to get out of the car and stand in a certain spot, "to here" he said a few hundred metres across the sand, where another soldier was told to stand. In this manner he mapped out a rectangle with a soldier in each corner. Then he drove off.

"But Your Highness," said Elliott. "What about the soldiers?"

"They're Bedouin," he replied, "They'll be fine."

Back in 1967 Elliott was 28 and freshly recruited from Scandinavia, where he had been working with municipalities on progressive - "people-empowered", as he calls it - town planning. The company that recruited him was an architecture and engineering consultancy called Arabicon, which was based in London and Abu Dhabi. They had been hired by Sheikh Zayed to oversee the creation of "a town", says Elliott. "We never talked about a city."

It must have been every town planner's dream. A blank slate (or at least a mostly blank desert). Added to which a man behind it with a vision that was exciting, to say the least.

At the time, about 4,000 people lived in Abu Dhabi emirate, mainly in Al Ain. In 1968, Sheikh Zayed ordered the first census of Abu Dhabi in an effort to get the regional nomadic tribes to settle in one place. "Anyone who called themselves an Abu Dhabian or said they were from Bani Yas was asked to turn up in Al Ain," Elliott recalls. "If they were accepted they received the princely sum of £1,000 [Dh5,832] in Marie Theresa silver talers, the common currency at the time, and were promised a national house."

The national houses, designed according to a brief by Sheikh Zayed, were built in 80ft by 80ft spaces. They were all identical, with a date store, a kitchen and a living room. In the

summer, people slept on the roofs. A lot of locals simply pitched their tents in the gardens and kept their goats and camels in the majlis.

"As a result of the census, 35,000 people showed up," says Elliott. "We had a big discussion about it in Arabicon and decided that the town would probably eventually be for a maximum of 350,000 people, and so the roads, drains, substations and everything were designed with that in mind."

When Elliott arrived in the city there was hardly anything here. "There was a strip of buildings near the palace and a few very small mosques," he says. "There was not one single asphalt road. There was no corniche, just a beach. The ships that came in had to anchor a mile offshore because it was so shallow, and all the materials came in by barge."

Watching the scene of the boats anchoring inspired Elliott to plan a series of canals for the city.

"I remember the barges were beached a few feet from the Arabicon office and seeing an almost biblical stream of tiny Yemenis trudging up a ramp with bags of cement on their shoulders for hours in the August sun. They would have a bowl of rice for lunch in the shelter of the Arabicon stairway and were kept going by a young man who played a flute made from copper piping.

"The plan was to put in canals from Bateen Creek to Sadyat Creek, east to west across the island, rather like the road system we ended up with, so that barges could bring the produce into the canals and unload and at the same time so we could use the land we dredged up while building the canals for landfill. We were going to have the roads going the other way.

"Sadly, it was too visionary. I was only 28 at the time; you're a dreamer at that age."

But he is still full of admiration for Sheikh Zayed. The combination of a young man who was "on fire about social welfare" and the Sheikh who wanted to lift up his people did produce a visionary town, even without the canals.

"It is strange that the Scandinavian social values that I arrived with should coincide so closely with Sheikh Zayed's vision and his commitment to Islam," says Elliott. "Sheikh Zayed had a vision of a garden city with parks and space and the Quranic values of the rights of people to a clean, safe environment. Initially working in London, 3,500 miles away, I had the same ideals, and my drawings and plans gave him what he wanted."

Did Sheikh Zayed draw out his plans for the town?

"I personally never saw Sheikh Zayed put pen to paper," says Elliott. "He always used a camel stick and drew in the sand. He had a unique ability to be able to transpose something from his head into the sand. And he instinctively understood scale and adjacency. I was lucky enough to be the first person to put his plans to paper, leaving an almost unchangeable imprint thereafter. It's probably unrepeatable. I carried them around with me rolled up everywhere, because at any given moment I could have been called upon to roll them out on a carpet in a majlis or up a sand dune somewhere. "

Sheikh Zayed insisted on as much green as possible in Abu Dhabi. "He really loved the idea of parks and trees," says Elliott, "and his vision was that families should be able to sit on the grass under trees. It was similar to the Scandinavian thing again, the tree-lined streets and the integration of inside and outside. But he had to have trees that could survive this climate, so he had an experimental garden in Al Ain where he had a Pakistani gardener who tried out all sorts of different plants."

Originally, each block was designed as a "family ghetto, with all the best meanings of the word", says Elliott. "The central area being an oasis which originally had trees. These were subsequently swept away by parking. My input included the slip roads and the roundabouts. Traffic lights were unnecessary because there wasn't the volume of traffic."

Elliott arrived to a different world than the one today. There were around 40 expatriates living here in 1967, and the locals were few and far between.

Elliott was the second man ever to water-ski under Maqta Bridge. "My friend Barry Newman was the first," he says. "But only because it was his boat."

Sheikh Zayed was very much a man of the people, and Elliott remembers him showing up at his house in his Land Rover one day. "He had driven down because of an incident with some falconers and some white doves I had. The doves had all been killed. I think he came with the intention to commiserate with me but got distracted by my composting machine. Anyway, that was the sort of man he was, the sort of man who would just show up in your garden. Anybody could talk to him at any time."

The city's development, was, in part, based on designs put forward as early as 1962 by the London-based company Sir William Halcrow & Partners and Scott & Wilson, Kirkpatrick and Partners. These earlier plans were presented to Sheikh Shakhbut and contained some extraordinary language, practically threatening the Ruler with a doomsday-like scenario should the plans not be accepted and requesting an up-front payment of £1 million, the equivalent of £25 million (Dh146 million) today.

The pressure on the sheikhs to get things moving for the development of their country and people was immense. Between 1962 and 1966 the Abu Dhabi leaders must have reviewed, discussed and studied the Halcrow plans for the city, resisting foreign pressure to turn Abu Dhabi into an oil town. As Claud Morris says in his 1974 book The Desert Falcon, "For the British, Abu Dhabi was oil and desert - in that order."

But the Sheikhs were intent on launching a nation, a home for their tribes, not building an oil town. "The plan for Abu Dhabi evolved around the social needs of the people," says Elliott.

Sheikh Zayed once said that "speed is part of the nature of the age", and the creation of Abu Dhabi happened with incredible speed once he assumed power, in 1966, having studied the relatively staid Halcrow master plan for four years.

"The 1962 plans would have been shown to every visitor and discussed in every majlis throughout the four years," says Zaki Nusseibeh, the Sheikh's linguist and translator.

Sheikh Zayed, having in effect taught himself master planning, then heard the explanation behind Elliott's innovations via his Egyptian friend, the Arabicon co-founder Ian Cuthbert. The Sheikh chose to pursue several of Elliott's cutting-edge town-planning concepts - namely Scandinavian-influenced urban design, wind-acceleration engineering and systematised utility culverts - that would accommodate a continual modernisation process. And he used the new team of Arabicon, formed six months earlier, to carry it off.

"It is hard to convey the speed with which it was all happening in 1966," says Elliott. "Once Sheikh Zayed had agreed to the initial design layout, we agreed to the coordinates with the surveyors on site, then the civil engineers and the team produced our drawings in Cobham, Surrey. Then they were couriered or carried back to Abu Dhabi and the contractors started building the roads. We're talking a matter of days here, not weeks."

indeed, from almost nothing, it took but a few years for the town to be well on its way to becoming the city it is now. It is extraordinary to imagine that initially only the northeastern corner of the island of Abu Dhabi was being developed. Khalidya began to take form in 1968, spearheaded by Dr Abdulrahman Makhlouf, a town planner from Egypt who incorporated some of the same principles of Sheikh Zayed and Elliott's 1966 plan, under the management of Sheikh Zayed's brother Khalid. Dr Makhlouf went on to become the second official town planner of Abu Dhabi.

Elliott says the city today is in many ways true to the vision of Sheikh Zayed, and he looks back on their cooperation with fondness. "Personally, I think the story is in the common vision," he says. "What created his and what led to mine, the application of the facts of climatically responsive architecture at an urban design level, which has rarely been achieved in practice, rather than the theory of Brasilia and the Ville Radieuse; the amazing similarity of aspirations of post-war socialist Europe and Islamic faith.

"So my conclusion is that my working relationship with Sheikh Zayed was a concordance. I Googled 'concordance' and with synonyms like 'compliance', 'compromise', 'compatibility', 'understanding', 'endorsing', even 'harmony', I think that is the word to describe the planning process for Abu Dhabi."

The numbers

40: Approximate number of expatriates in Abu Dhabi when John Elliott arrived in 1967

80: In feet, the dimension of each side of the "national houses" that Sheikh Zayed planned for the locals

4000: Abu Dhabi population in 1967

35,000: Number of people who showed up for the first Abu Dhabi census in 1968

350,000: Eventual population Arabicon planners envisioned in 1968

1.64m: Abu Dhabi population today

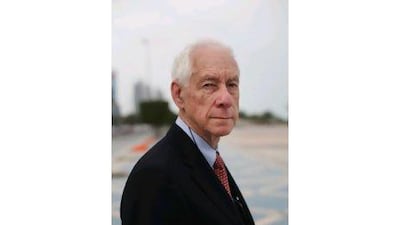

EDITOR'S NOTE: John Elliott died suddenly at the age of 73 on September 13 after a two-week bout of pneumonia, not long after Ann Wimsatt interviewed him for this article. Before Wimsatt - a director of Williams and Wimsatt Architects Ltd whose book, "Tempered Idealism And The City Plan Of Abu Dhabi", is due to be published in 2011 - no one had previously interviewed Elliott about his experience and contribution to Abu Dhabi.