Arabian Gulf energy exporters are looking for their main energy partner in Asia. Like the protagonist in Vikram Seth’s “A Suitable Boy”, all of the candidates appeal but none are perfect. A flurry of activity in recent weeks has moved exciting India ahead of reliable Japan and lucrative China.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi arrived in Abu Dhabi on Friday, his third trip in four years. Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed visited India in February, when Adnoc chief executive Dr Sultan Al Jaber signed an agreement for oil storage in the country. ONGC Videsh, the main Indian government oil company, along with state firms Bharat Petroleum and Indian Oil Corporation (IOC), have taken stakes in Abu Dhabi’s oil production and exploration licences.

Saudi Aramco and Adnoc are planning a $60 billion (Dh220.4bn) refinery and petrochemicals complex in India, in partnership with Bharat, IOC and a third state company, Hindustan Petroleum. Initially to be at Ratnagiri in Maharashtra state on India’s west coast, land acquisition problems seem to have pushed it to Raigad, 250 kilometres further north and closer to Mumbai.

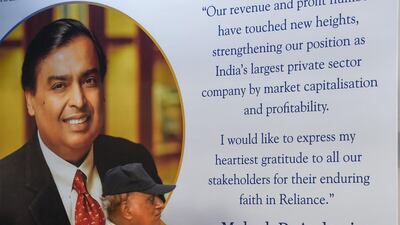

Last week, Aramco’s inaugural earnings call covered preliminary plans to pay $15bn for 20 per cent of Indian private conglomerate Reliance Industries’ refining and petrochemicals business. The reported price for the stake in Reliance, significantly above multiples for comparable deals, shows the importance of Aramco’s introduction to India. This urgency would be reinforced if the Maharashtra refinery is further delayed.

While China has been wooed for years, and Aramco already has joint-venture refineries there, India is increasingly the key future energy market. The US has largely disappeared as an oil and gas importer because of its shale boom, while environmental pressures and mature economies and demographics see the appetites of Europe and Japan for hydrocarbons slipping. Other Asian markets such as Vietnam, Indonesia, Pakistan and the Philippines are fast growing, but none can compare in scale with the two continental giants.

India’s population of 1.3 billion will likely outstrip China’s as early as 2024. After lagging China for more than a decade, Indian economic growth has been a little higher than its Asian rival since 2014, and estimated expansion this year of 6.2 per cent would match the Middle Kingdom’s. China’s economy is maturing and growth is slowing, even before the current escalating trade war with the US.

India remains much less wealthy, and uses barely a quarter of the energy per person, and less than a quarter of the petrochemicals that are used to make plastics in many consumer and construction products. Officially, there are only 22 motor vehicles (excluding motorcycles) per thousand Indians, compared to 179 in China.

Several of Mr Modi’s aims are likely to boost energy demand. His government has not quite achieved its goal of tripling road building, but highway construction has doubled. Poorer and rural households have been offered loans and subsidies to switch to using bottled gas for cooking instead of polluting wood, dung and kerosene. In April last year, it was announced that all villages in the country had been connected to electricity, though around 200 million people remain without.

All these statistics suggest that, while China remains the incumbent, India offers brighter long-term energy prospects. Yet there are several challenges in the way.

In the immediate future, the fears of global recession and trade barriers are affecting India too, with its growth prospects downgraded. Despite the “Make in India” aim of boosting manufacturing to a quarter of the economy, it remains stubbornly stuck around 15 per cent.

Its lively and fractious democracy and federal structure should be more sustainable than its northern neighbour’s authoritarian capitalism, but can hinder big infrastructure and industrial projects, such as the Maharashtra refinery. Crowded cities and gridlock limit the practical number of private vehicles, and fuel prices are significantly higher than in the US and China.

While China has moved boldly in the past couple of years to replace coal with natural gas to clean up its notoriously filthy air, India’s cities have become the most polluted in the world, occupying 22 out of the bottom 30 slots. Annual gas consumption has not grown since 2010, held back by insufficient domestic supply, high prices for imports and a preference for cheap domestic coal.

With rival Pakistan, insecure Afghanistan and US-sanctioned Iran to the north-west effectively barring land access to Middle Eastern and Central Asian gas, Delhi has to rely on liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports that are usually more expensive and perceived as less secure. The current glut of LNG might be gas’s opportunity finally to make some inroads.

India’s energy dowry will not be paid solely in fossil fuels. Since 2017, the country has added 11.1 gigawatts of coal power, but 30.4 gigawatts of solar and wind. Electric rickshaws and motorbikes are popular. Larger battery vehicles have struggled for traction, but policies to encourage local manufacturing of electric cars, offer subsidies and cut sales taxes may lead to progress towards the impossibly ambitious target of phasing out oil-fuelled vehicle sales by 2030.

In the longer term, climate change threatens the reliability of the monsoon, and the Himalayan glaciers that supply the Ganges, the Brahmaputra and the rivers of Indian-administered Kashmir that join the Indus. Agriculture still employs more than two-fifths of Indians, making climate a direct issue of jobs, economics and votes.

India’s tremendous economic and energy future explains its assiduous courting by leading national oil companies. However, its political and regional complexities, environmental and infrastructure challenges mean its energy story will not repeat China’s trajectory. Prospective partners can prosper, if they prepare.

Robin Mills is CEO of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis

Profile of Bitex UAE

Date of launch: November 2018

Founder: Monark Modi

Based: Business Bay, Dubai

Sector: Financial services

Size: Eight employees

Investors: Self-funded to date with $1m of personal savings

The years Ramadan fell in May

ALRAWABI%20SCHOOL%20FOR%20GIRLS

%3Cp%3ECreator%3A%20Tima%20Shomali%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EStarring%3A%C2%A0Tara%20Abboud%2C%C2%A0Kira%20Yaghnam%2C%20Tara%20Atalla%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ERating%3A%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

COMPANY PROFILE

Name: Almnssa

Started: August 2020

Founder: Areej Selmi

Based: Gaza

Sectors: Internet, e-commerce

Investments: Grants/private funding

THE SPECS

Engine: 1.5-litre turbocharged four-cylinder

Transmission: Constant Variable (CVT)

Power: 141bhp

Torque: 250Nm

Price: Dh64,500

On sale: Now

The specs

- Engine: 3.9-litre twin-turbo V8

- Power: 640hp

- Torque: 760nm

- On sale: 2026

- Price: Not announced yet

The specs

Price, base / as tested Dh1,100,000 (est)

Engine 5.2-litre V10

Gearbox seven-speed dual clutch

Power 630bhp @ 8,000rpm

Torque 600Nm @ 6,500rpm

Fuel economy, combined 15.7L / 100km (est)

What can victims do?

Always use only regulated platforms

Stop all transactions and communication on suspicion

Save all evidence (screenshots, chat logs, transaction IDs)

Report to local authorities

Warn others to prevent further harm

Courtesy: Crystal Intelligence

The biog

Job: Fitness entrepreneur, body-builder and trainer

Favourite superhero: Batman

Favourite quote: We must become the change we want to see, by Mahatma Gandhi.

Favourite car: Lamborghini

Dubai Women's Tour teams

Agolico BMC

Andy Schleck Cycles-Immo Losch

Aromitalia Basso Bikes Vaiano

Cogeas Mettler Look

Doltcini-Van Eyck Sport

Hitec Products – Birk Sport

Kazakhstan National Team

Kuwait Cycling Team

Macogep Tornatech Girondins de Bordeaux

Minsk Cycling Club

Pannonia Regional Team (Fehérvár)

Team Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes

Team Ciclotel

UAE Women’s Team

Under 23 Kazakhstan Team

Wheel Divas Cycling Team

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

The%20Little%20Mermaid%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Rob%20Marshall%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EHalle%20Bailey%2C%20Jonah%20Hauer-King%2C%20Melissa%20McCarthy%2C%20Javier%20Bardem%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2%2F5%3Cbr%3E%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Teenage%20Mutant%20Ninja%20Turtles%3A%20Shredder's%20Revenge

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDeveloper%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ETribute%20Games%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPublisher%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dotemu%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EConsoles%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENintendo%20Switch%2C%20PlayStation%204%26amp%3B5%2C%20PC%20and%20Xbox%20One%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Dirham Stretcher tips for having a baby in the UAE

Selma Abdelhamid, the group's moderator, offers her guide to guide the cost of having a young family:

• Buy second hand stuff

They grow so fast. Don't get a second hand car seat though, unless you 100 per cent know it's not expired and hasn't been in an accident.

• Get a health card and vaccinate your child for free at government health centres

Ms Ma says she discovered this after spending thousands on vaccinations at private clinics.

• Join mum and baby coffee mornings provided by clinics, babysitting companies or nurseries.

Before joining baby classes ask for a free trial session. This way you will know if it's for you or not. You'll be surprised how great some classes are and how bad others are.

• Once baby is ready for solids, cook at home

Take the food with you in reusable pouches or jars. You'll save a fortune and you'll know exactly what you're feeding your child.

Lexus LX700h specs

Engine: 3.4-litre twin-turbo V6 plus supplementary electric motor

Power: 464hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 790Nm from 2,000-3,600rpm

Transmission: 10-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 11.7L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh590,000

Porsche Macan T: The Specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4-cyl turbo

Power: 265hp from 5,000-6,500rpm

Torque: 400Nm from 1,800-4,500rpm

Transmission: 7-speed dual-clutch auto

Speed: 0-100kph in 6.2sec

Top speed: 232kph

Fuel consumption: 10.7L/100km

On sale: May or June

Price: From Dh259,900

The%20specs

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E3.0-litre%20twin-turbo%20V6%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E10-speed%20auto%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E400bhp%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E563Nm%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDh320%2C000%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EOn%20sale%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Now%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The biog

Favourite films: Casablanca and Lawrence of Arabia

Favourite books: Start with Why by Simon Sinek and Good to be Great by Jim Collins

Favourite dish: Grilled fish

Inspiration: Sheikh Zayed's visionary leadership taught me to embrace new challenges.

No_One Ever Really Dies

N*E*R*D

(I Am Other/Columbia)

THE CLOWN OF GAZA

Director: Abdulrahman Sabbah

Starring: Alaa Meqdad

Rating: 4/5

RIVER%20SPIRIT

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EAuthor%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ELeila%20Aboulela%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPublisher%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Saqi%20Books%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPages%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20320%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EAvailable%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Now%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Ferrari 12Cilindri specs

Engine: naturally aspirated 6.5-liter V12

Power: 819hp

Torque: 678Nm at 7,250rpm

Price: From Dh1,700,000

Available: Now

Heather, the Totality

Matthew Weiner,

Canongate

Engine: 80 kWh four-wheel-drive

Transmission: eight-speed automatic

Power: 402bhp

Torque: 760Nm

Price: From Dh280,000

At a glance - Zayed Sustainability Prize 2020

Launched: 2008

Categories: Health, energy, water, food, global high schools

Prize: Dh2.2 million (Dh360,000 for global high schools category)

Winners’ announcement: Monday, January 13

Impact in numbers

335 million people positively impacted by projects

430,000 jobs created

10 million people given access to clean and affordable drinking water

50 million homes powered by renewable energy

6.5 billion litres of water saved

26 million school children given solar lighting

Company%20profile

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EName%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Envi%20Lodges%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESeptember%202021%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ECo-founders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Noelle%20Homsy%20and%20Chris%20Nader%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20UAE%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Hospitality%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ENumber%20of%20employees%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2012%20to%2015%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStage%20of%20investment%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESeries%20A%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

All%20We%20Imagine%20as%20Light

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EPayal%20Kapadia%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarring%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Kani%20Kusruti%2C%20Divya%20Prabha%2C%20Chhaya%20Kadam%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A