Climate change presents a grave threat to macroeconomic and financial stability and policymakers attending Cop26 must address critical gaps in ambition and policy to achieve emissions curbs that can help to contain global warming, according to the International Monetary Fund.

The window of opportunity for limiting global warming to 1.5°C to 2°C above pre-industrial levels is closing rapidly, the fund said in a note late on Sunday, the first day of the Cop26 meeting of world leaders in Glasgow.

The Paris Agreement provides a mandate for countries to lower their carbon emissions to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, preferably at about 1.5°C.

IMF managing director

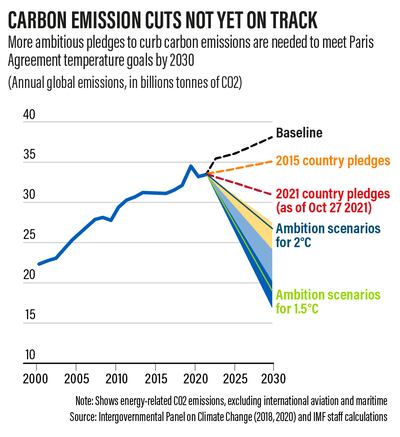

“Unchanged global policies will leave 2030 carbon emissions far higher than needed to keep 1.5°C alive,” said IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva.

“Cuts of 55 per cent below baseline levels in 2030 would be urgently needed to meet that goal and of 30 per cent to meet the 2°C objective.”

World leaders at the conference will aim to strengthen commitments made in Paris in 2015 to stabilise the planet’s climate and look to speed up action to achieve a zero-carbon future by 2050.

Limiting global warming to the Paris Agreement mandate requires cutting global carbon emissions by 25 per cent to 50 per cent below 2021 levels by 2030, followed by a steady decline to net-zero emissions near the middle of this century, the Washington-based lender said.

“Despite countries variably committing to net-zero emissions targets and strengthening 2030 targets, there remains a large near-term gap in mitigation ambition,” Ms Georgieva said.

About 135 countries accounting for more than three quarters of global greenhouse gas emissions have committed to net zero by mid-century. But they fall short in pledges for the near term, the fund said.

Even if current commitments for 2030 were met, this would only amount to between one third and two thirds of the reductions needed for temperature goals, according to the IMF.

The IMF called for enhanced external financing to support stronger mitigation ambition for emerging markets and developing economies.

Advanced economies must fulfil their commitment to provide $100 billion a year in finance to low-income countries from 2020 onwards, the fund said.

The fund also proposed an international carbon price floor among a small group of large emitters. Such a floor would be equitable, with different prices for countries at different levels of economic development, alongside financial and technological assistance for low-income participants.

A carbon price puts a specific value on a tonne of carbon emitted by an industry, thereby making it more expensive to pollute the environment. A carbon price floor imposes a tax on fossil fuels to incentivise investment in low-carbon alternatives.

A global carbon price exceeding $75 a tonne would be needed by 2030 to keep warming below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, the multilateral lender said.

It also urged countries to scale up green public investment and hasten the adoption of clean technology infrastructure such as smart grids and charging stations for electric vehicles.

“Without an urgent narrowing of ambition, policy and financing gaps, a dangerous cliff edge for emissions reductions beyond 2030 will be set up, greatly increasing transition costs and potentially putting temperature goals permanently beyond reach,” the IMF said.