As a boy growing up in 1950s South Korea, Jooho Whang had seen nuclear power plants only in science fiction cartoons. At the time, atomic power in his homeland was a distant dream.

The country was emerging from the shadow of a devastating war with North Korea, and its per capita GDP was a mere US$876 (Dh3,217).

So when in 1987, after several years out of the country, Jooho Whang came face to face with the nuclear reactor Kori 1, the nation's first, he was struck with awe.

"It was the first constructed building I ever saw that was built so fancy," says the nuclear scientist, laughing at the joy of the memory. "I was overwhelmed by concrete structures containing shiny stainless steel tanks and pipes going this way and that way. It was beautiful."

Mr Whang was an early recruit to his country's nuclear programme. Kori 1 had begun powering homes and industry in 1978, the first of 23 reactors that would ultimately produce a third of the nation's electricity.

The power from those plants has fuelled South Korea's rapid transformation from a developing economy to one that today donates to poorer nations.

A former importer of nuclear technology and know-how from the United States, South Korea has transformed itself into an exporter, with Abu Dhabi its first customer. And it steps into the limelight this week as the host of an international summit on nuclear security backed by the US president Barack Obama.

Mr Whang, who is the president of the Korea Institute for Energy Research, was in Kuwait this month for talks on a project to test Korean-designed solar-powered homes. Sitting in the gold-bedecked lobby of Kuwait City's Hotel Missoni, Mr Whang could not have been farther from the Korea of his childhood.

But the country's remarkable economic transformation has created a society that is today more questioning, more concerned and hungrier for information - including on nuclear matters.

"The basic issue is this: Korea has enjoyed an extremely high level of public confidence in its nuclear programme for 35 years," says Mark Hibbs, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "And the more wealthy it gets, the more internationally connected Korea gets, the more difficult it will be to move ahead."

A report from the Nuclear Safety and Security Commission, the Korean regulator, this month detailed a power system failure at Kori 1 in February while it was in cold shut down.

The cooling systems for the reactor core and spent-fuel ponds stopped working, sending the temperature of the core coolant soaring from 36.9¿C to 58.3¿C and the spent-fuel ponds from 0.5¿C to 20.5¿C within 12 minutes. Staff did not report the anomaly immediately and deleted records of it, according to the report.

In response to the Kori 1 incident, Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power, the plant operator, fired the plant manager, according to the Yonhap News agency. It now faces prosecution by the regulator. In Seoul last week, Kim Jong-shin, the chief executive, downplayed the matter but pledged to bring in international experts to advise on improving safety standards.

"It was an isolated case, and it was initiated by a very, very minor workman's error," Mr Kim said on the sidelines of an industry conference. "In terms of transparency, I will try to work more from the people's perspective and spread the safety culture."

Mr Kim and others in the industry have come under the scrutiny of the Korean media amid concerns about transparency and the safety of ageing reactors, especially among a public already frightened by the emergency that began last March in Fukushima, Japan.

South Korea is also grappling with dilemmas such as where to store radioactive spent fuel over the long term, a controversial matter that has yet to be resolved even in the US. On the eve of this week's nuclear summit in Seoul, protesters near the main convention centre held signs with the words "No Nuke". "These were not pressing questions two decades ago," says Mr Hibbs. "It's natural and inevitable that as Korea becomes more internationally connected, its public becomes more aware of the risks of nuclear energy."

It is a different world than the one that Mr Whang encountered when he was entering the field in 1975.

He enrolled in a nuclear engineering programme because "it sounded very fancy". At the time South Korea had no nuclear plants; Kori 1 was in its fourth year of construction, and was three years away from producing power.

The government was intent on recruiting its best and brightest to the nuclear programme, both from inside the country and among Koreans who had moved abroad to study and work.

The oil price shock of 1973 had made it clear that South Korea needed to diversify beyond fossil fuels and finding itself at the mercy of market prices.

But there was one problem. The country depended on export-credit financing to pay for the major up-front investment in nuclear power. It wanted to become self-reliant, and that required getting rights to its own nuclear technology. "We knew we could not start from scratch. We knew we had to import state-of-the-art technology. Our stipulation was, who would give us the best technology transfer?" says Kim Byung-koo, a mechanical engineer working at Nasa who was recruited back to South Korea in 1975 to the Korean Atomic Energy Research Institute.

"Of course, Korea exporting nuclear seemed such a remote dream at the time," he says.

South Korea began negotiating with three international vendors. Its proposal to the vendors that they forgo a royalty, should Korea ever export the technology, was met with laughter. But the tenor of the talks shifted in 1986 when the disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine put a damper on the nuclear programme worldwide.

"It turned out to be such a big blessing for Korea, because everyone just shut down. New projects were just thrown out the window and existing nuclear plants were put under moratorium," says Mr Kim. "In the nuclear market, there were no buyers - except Korea.

"Because of Chernobyl, the contract negotiations became so much in our favour. We could say anything and they couldn't say no."

South Korea signed a deal with an American vendor that would allow the country to receive the technology and export it in the future without a royalty. That laid the foundation for its export contract with the UAE more than two decades later.

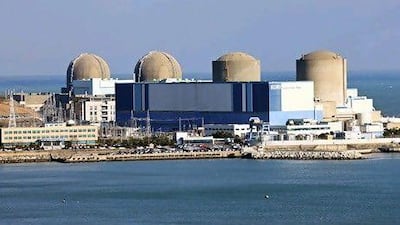

On Korea's south-east coast, the squat lines of the 600-megawatt Kori 1 power station lie just a kilometre or two south of the construction sites for the latest model in Korean nuclear technology - the APR 1400, which is also expected to be built in Abu Dhabi. Cranes loom above the reactors' concrete domes, and beyond them lies the open sea.

ayee@thenational.ae

twitter: Follow our breaking business news and retweet to your followers. Follow us

Dengue%20fever%20symptoms

%3Cp%3EHigh%20fever%20(40%C2%B0C%2F104%C2%B0F)%3Cbr%3ESevere%20headache%3Cbr%3EPain%20behind%20the%20eyes%3Cbr%3EMuscle%20and%20joint%20pains%3Cbr%3ENausea%3Cbr%3EVomiting%3Cbr%3ESwollen%20glands%3Cbr%3ERash%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

A Cat, A Man, and Two Women

Junichiro Tamizaki

Translated by Paul McCarthy

Daunt Books

The specs

Engine: 8.0-litre, quad-turbo 16-cylinder

Transmission: 7-speed auto

0-100kmh 2.3 seconds

0-200kmh 5.5 seconds

0-300kmh 11.6 seconds

Power: 1500hp

Torque: 1600Nm

Price: Dh13,400,000

On sale: now

Liz%20Truss

%3Cp%3EMinisterial%20experience%3A%20Current%20Foreign%20Secretary.%0D%3Cbr%3E%0DWhat%20did%20she%20do%20before%20politics%3F%20Worked%20as%20an%20economist%20for%20Shell%20and%20Cable%20and%20Wireless%20and%20was%20then%20a%20deputy%20director%20for%20right-of-centre%20think%20tank%20Reform.%0D%3Cbr%3E%0DWhat%20does%20she%20say%20on%20tax%3F%20She%20has%20pledged%20to%20%22start%20cutting%20taxes%20from%20day%20one%22%2C%20reversing%20April's%20rise%20in%20National%20Insurance%20and%20promising%20to%20keep%20%22corporation%20tax%20competitive%22.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

Some of Darwish's last words

"They see their tomorrows slipping out of their reach. And though it seems to them that everything outside this reality is heaven, yet they do not want to go to that heaven. They stay, because they are afflicted with hope." - Mahmoud Darwish, to attendees of the Palestine Festival of Literature, 2008

His life in brief: Born in a village near Galilee, he lived in exile for most of his life and started writing poetry after high school. He was arrested several times by Israel for what were deemed to be inciteful poems. Most of his work focused on the love and yearning for his homeland, and he was regarded the Palestinian poet of resistance. Over the course of his life, he published more than 30 poetry collections and books of prose, with his work translated into more than 20 languages. Many of his poems were set to music by Arab composers, most significantly Marcel Khalife. Darwish died on August 9, 2008 after undergoing heart surgery in the United States. He was later buried in Ramallah where a shrine was erected in his honour.

Ain Dubai in numbers

126: The length in metres of the legs supporting the structure

1 football pitch: The length of each permanent spoke is longer than a professional soccer pitch

16 A380 Airbuses: The equivalent weight of the wheel rim.

9,000 tonnes: The amount of steel used to construct the project.

5 tonnes: The weight of each permanent spoke that is holding the wheel rim in place

192: The amount of cable wires used to create the wheel. They measure a distance of 2,4000km in total, the equivalent of the distance between Dubai and Cairo.

The specs

Engine: 3.8-litre twin-turbo flat-six

Power: 650hp at 6,750rpm

Torque: 800Nm from 2,500-4,000rpm

Transmission: 8-speed dual-clutch auto

Fuel consumption: 11.12L/100km

Price: From Dh796,600

On sale: now

The National's picks

4.35pm: Tilal Al Khalediah

5.10pm: Continous

5.45pm: Raging Torrent

6.20pm: West Acre

7pm: Flood Zone

7.40pm: Straight No Chaser

8.15pm: Romantic Warrior

8.50pm: Calandogan

9.30pm: Forever Young

First Person

Richard Flanagan

Chatto & Windus

Company%20profile

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EXare%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EJanuary%2018%2C%202021%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EPadmini%20Gupta%2C%20Milind%20Singh%2C%20Mandeep%20Singh%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDubai%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFinTech%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFunds%20Raised%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2410%20million%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECurrent%20number%20of%20staff%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E28%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestment%20stage%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3Eundisclosed%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EMS%26amp%3BAD%20Ventures%2C%20Middle%20East%20Venture%20Partners%2C%20Astra%20Amco%2C%20the%20Dubai%20International%20Financial%20Centre%2C%20Fintech%20Fund%2C%20500%20Startups%2C%20Khwarizmi%20Ventures%2C%20and%20Phoenician%20Funds%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The%20specs%3A%202024%20Mercedes%20E200

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2.0-litre%20four-cyl%20turbo%20%2B%20mild%20hybrid%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E204hp%20at%205%2C800rpm%20%2B23hp%20hybrid%20boost%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E320Nm%20at%201%2C800rpm%20%2B205Nm%20hybrid%20boost%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E9-speed%20auto%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFuel%20consumption%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E7.3L%2F100km%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EOn%20sale%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENovember%2FDecember%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFrom%20Dh205%2C000%20(estimate)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The specs

AT4 Ultimate, as tested

Engine: 6.2-litre V8

Power: 420hp

Torque: 623Nm

Transmission: 10-speed automatic

Price: From Dh330,800 (Elevation: Dh236,400; AT4: Dh286,800; Denali: Dh345,800)

On sale: Now

START-UPS%20IN%20BATCH%204%20OF%20SANABIL%20500'S%20ACCELERATOR%20PROGRAMME

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ESaudi%20Arabia%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EJoy%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Delivers%20car%20services%20with%20affordable%20prices%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EKaraz%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Helps%20diabetics%20with%20gamification%2C%20IoT%20and%20real-time%20data%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMedicarri%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Medical%20marketplace%20that%20connects%20clinics%20with%20suppliers%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMod5r%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3A%20Makes%20automated%20and%20recurring%20investments%20to%20grow%20wealth%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStuck%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Live%2C%20on-demand%20language%20support%20to%20boost%20writing%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EWalzay%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Helps%20in%20recruitment%20while%20reducing%20hiring%20time%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EUAE%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEighty6%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EMarketplace%20for%20restaurant%20and%20supplier%20procurements%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFarmUnboxed%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EHelps%20digitise%20international%20food%20supply%20chain%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ENutriCal%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Helps%20F%26amp%3BB%20businesses%20and%20governments%20with%20nutritional%20analysis%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EWellxai%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Provides%20insurance%20that%20enables%20and%20rewards%20user%20habits%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEgypt%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EAmwal%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20A%20Shariah-compliant%20crowd-lending%20platform%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDeben%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Helps%20CFOs%20manage%20cash%20efficiently%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEgab%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Connects%20media%20outlets%20to%20journalists%20in%20hard-to-reach%20areas%20for%20exclusives%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ENeqabty%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Digitises%20financial%20and%20medical%20services%20of%20labour%20unions%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EOman%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMonak%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Provides%20financial%20inclusion%20and%20life%20services%20to%20migrants%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4-cylinder turbo

Power: 240hp at 5,500rpm

Torque: 390Nm at 3,000rpm

Transmission: eight-speed auto

Price: from Dh122,745

On sale: now

The specS: 2018 Toyota Camry

Price: base / as tested: Dh91,000 / Dh114,000

Engine: 3.5-litre V6

Gearbox: Eight-speed automatic

Power: 298hp @ 6,600rpm

Torque: 356Nm @ 4,700rpm

Fuel economy, combined: 7.0L / 100km