Scientists say they have found the 'key ingredients' to create the first nuclear clock which could advance understanding of time and fundamental physics.

A nuclear clock is a theoretical timekeeping device that measures signals from the nucleus of an atom to provide its 'ticks'.

Although its potential excites scientists, until now it has not been replicated owing to the difficulty of measuring the energy jumps within a nucleus using current technology.

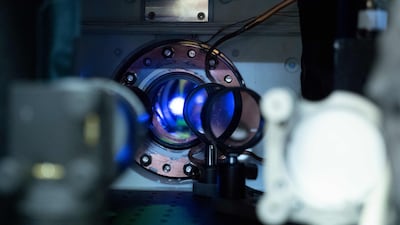

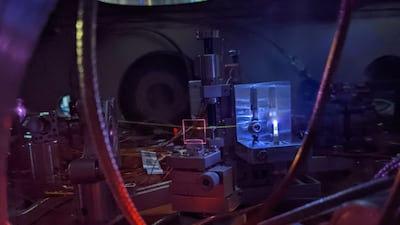

Researchers at JILA, a joint institute of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado Boulder, were able to utilise a ultraviolet laser to precisely measure the frequency of an energy jump in thorium nuclei embedded in a solid crystal.

While this laboratory demonstration is not a fully developed nuclear clock, it contains all the core technology for one, the scientists say.

“We used a laser referenced to the most precise atomic clock to excite the nucleus of thorium atoms and measure the absolute frequency of the nuclear transition”, researchers told The National.

They added that the measurement was “a million times more precise than previous experiments”.

The research has already yielded unprecedented results, including the ability to observe details in the thorium nucleus's shape that no one had ever observed before. Researchers liken this to seeing individual blades of grass from an aircraft.

Atomic clocks are used to configure international time and play major roles in technologies such as GPS, internet synchronisation, and financial transactions.

Nuclear clocks are generally thought to be more precise than atomic clocks, which measure time by tuning laser light to frequencies that cause electrons to jump between energy levels.

The development of nuclear clocks could mean even more precise navigation systems, faster internet speeds, more reliable network connections and more secure digital communications.

“Imagine a wristwatch that wouldn't lose a second even if you left it running for billions of years,” said NIST and JILA physicist Jun Ye. “While we're not quite there yet, this research brings us closer to that level of precision.”

Scientists focused on thorium-229, an atom whose nucleus has a smaller energy jump than any other known atom, requiring ultraviolet light, which is lower in energy than X-rays.

“Since a nuclear clock is based on a nuclear transition within an atom's nucleus as opposed to an electron transition occurring in the atom's electron shell, nuclear clocks can be less sensitive to issues such as electric magnetic fields”, the researchers added.

“Another simple reason is that the frequency of the thorium nuclear transition is higher than most atomic clock frequencies – in general, a clock that ticks faster is able to measure time with more precision.”

Nuclear clocks could further improve tests of fundamental theories for how the universe works, potentially leading to new discoveries in physics.

For example, they could help detect dark matter or verify if the constants of nature are truly constant, allowing for verification of theories in particle physics without the need for large-scale particle accelerator facilities.

Despite the exciting breakthrough, researchers believe that it would take some time for a nuclear clock to surpass the world's best atomic clocks, adding that both were complimentary to each other, especially when it comes to studying fundamental physics.

The specs: 2018 Mercedes-AMG C63 S Cabriolet

Price, base: Dh429,090

Engine 4.0-litre twin-turbo V8

Transmission Seven-speed automatic

Power 510hp @ 5,500rpm

Torque 700Nm @ 1,750rpm

Fuel economy, combined 9.2L / 100km

Mobile phone packages comparison

How does ToTok work?

The calling app is available to download on Google Play and Apple App Store

To successfully install ToTok, users are asked to enter their phone number and then create a nickname.

The app then gives users the option add their existing phone contacts, allowing them to immediately contact people also using the application by video or voice call or via message.

Users can also invite other contacts to download ToTok to allow them to make contact through the app.

The%20specs%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDual%20permanently%20excited%20synchronous%20motors%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E516hp%20or%20400Kw%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E858Nm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESingle%20speed%20auto%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERange%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E485km%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFrom%20Dh699%2C000%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Avatar: Fire and Ash

Director: James Cameron

Starring: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Zoe Saldana

Rating: 4.5/5

Infiniti QX80 specs

Engine: twin-turbocharged 3.5-liter V6

Power: 450hp

Torque: 700Nm

Price: From Dh450,000, Autograph model from Dh510,000

Available: Now

The%20Woman%20King%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Gina%20Prince-Bythewood%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Viola%20Davis%2C%20Thuso%20Mbedu%2C%20Sheila%20Atim%2C%20Lashana%20Lynch%2C%20John%20Boyega%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%203%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

FIXTURES

All times UAE ( 4 GMT)

Saturday

Fiorentina v Torino (8pm)

Hellas Verona v Roma (10.45pm)

Sunday

Parma v Napoli (2.30pm)

Genoa v Crotone (5pm)

Sassuolo v Cagliari (8pm)

Juventus v Sampdoria (10.45pm)

Monday

AC Milan v Bologna (10.45om)

Playing September 30

Benevento v Inter Milan (8pm)

Udinese v Spezia (8pm)

Lazio v Atalanta (10.45pm)

NEW%20PRICING%20SCHEME%20FOR%20APPLE%20MUSIC%2C%20TV%2B%20AND%20ONE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EApple%20Music%3Cbr%3EMonthly%20individual%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2410.99%20(from%20%249.99)%3Cstrong%3E%3Cbr%3EMonthly%20family%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2416.99%20(from%20%2414.99)%3Cstrong%3E%3Cbr%3EIndividual%20annual%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%24109%20(from%20%2499)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EApple%20TV%2B%3Cbr%3EMonthly%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%246.99%20(from%20%244.99)%3Cstrong%3E%3Cbr%3EAnnual%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2469%20(from%20%2449.99)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EApple%20One%3Cbr%3EMonthly%20individual%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2416.95%20(from%20%2414.95)%3Cstrong%3E%3Cbr%3EMonthly%20family%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2422.95%20(from%20%2419.95)%3Cstrong%3E%3Cbr%3EMonthly%20premier%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2432.95%20(from%20%2429.95)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

German intelligence warnings

- 2002: "Hezbollah supporters feared becoming a target of security services because of the effects of [9/11] ... discussions on Hezbollah policy moved from mosques into smaller circles in private homes." Supporters in Germany: 800

- 2013: "Financial and logistical support from Germany for Hezbollah in Lebanon supports the armed struggle against Israel ... Hezbollah supporters in Germany hold back from actions that would gain publicity." Supporters in Germany: 950

- 2023: "It must be reckoned with that Hezbollah will continue to plan terrorist actions outside the Middle East against Israel or Israeli interests." Supporters in Germany: 1,250

Source: Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

MOUNTAINHEAD REVIEW

Starring: Ramy Youssef, Steve Carell, Jason Schwartzman

Director: Jesse Armstrong

Rating: 3.5/5

Mercer, the investment consulting arm of US services company Marsh & McLennan, expects its wealth division to at least double its assets under management (AUM) in the Middle East as wealth in the region continues to grow despite economic headwinds, a company official said.

Mercer Wealth, which globally has $160 billion in AUM, plans to boost its AUM in the region to $2-$3bn in the next 2-3 years from the present $1bn, said Yasir AbuShaban, a Dubai-based principal with Mercer Wealth.

“Within the next two to three years, we are looking at reaching $2 to $3 billion as a conservative estimate and we do see an opportunity to do so,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Mercer does not directly make investments, but allocates clients’ money they have discretion to, to professional asset managers. They also provide advice to clients.

“We have buying power. We can negotiate on their (client’s) behalf with asset managers to provide them lower fees than they otherwise would have to get on their own,” he added.

Mercer Wealth’s clients include sovereign wealth funds, family offices, and insurance companies among others.

From its office in Dubai, Mercer also looks after Africa, India and Turkey, where they also see opportunity for growth.

Wealth creation in Middle East and Africa (MEA) grew 8.5 per cent to $8.1 trillion last year from $7.5tn in 2015, higher than last year’s global average of 6 per cent and the second-highest growth in a region after Asia-Pacific which grew 9.9 per cent, according to consultancy Boston Consulting Group (BCG). In the region, where wealth grew just 1.9 per cent in 2015 compared with 2014, a pickup in oil prices has helped in wealth generation.

BCG is forecasting MEA wealth will rise to $12tn by 2021, growing at an annual average of 8 per cent.

Drivers of wealth generation in the region will be split evenly between new wealth creation and growth of performance of existing assets, according to BCG.

Another general trend in the region is clients’ looking for a comprehensive approach to investing, according to Mr AbuShaban.

“Institutional investors or some of the families are seeing a slowdown in the available capital they have to invest and in that sense they are looking at optimizing the way they manage their portfolios and making sure they are not investing haphazardly and different parts of their investment are working together,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Some clients also have a higher appetite for risk, given the low interest-rate environment that does not provide enough yield for some institutional investors. These clients are keen to invest in illiquid assets, such as private equity and infrastructure.

“What we have seen is a desire for higher returns in what has been a low-return environment specifically in various fixed income or bonds,” he said.

“In this environment, we have seen a de facto increase in the risk that clients are taking in things like illiquid investments, private equity investments, infrastructure and private debt, those kind of investments were higher illiquidity results in incrementally higher returns.”

The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, one of the largest sovereign wealth funds, said in its 2016 report that has gradually increased its exposure in direct private equity and private credit transactions, mainly in Asian markets and especially in China and India. The authority’s private equity department focused on structured equities owing to “their defensive characteristics.”

The specs

- Engine: 3.9-litre twin-turbo V8

- Power: 640hp

- Torque: 760nm

- On sale: 2026

- Price: Not announced yet

More from Rashmee Roshan Lall

Desert Warrior

Starring: Anthony Mackie, Aiysha Hart, Ben Kingsley

Director: Rupert Wyatt

Rating: 3/5

MOTHER%20OF%20STRANGERS

%3Cp%3EAuthor%3A%20Suad%20Amiry%3Cbr%3EPublisher%3A%20Pantheon%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EPages%3A%20304%3Cbr%3EAvailable%3A%20Now%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Stage 2 results

1 Caleb Ewan (AUS) Lotto Soudal 04:18:18

2 Sam Bennett (IRL) Deceuninck-QuickStep 00:00:02

3 Arnaud Demare (FRA) Groupama-FDJ 00:00:04

4 Diego Ulissi (ITA) UAE Team Emirates

5 Rick Zabel (GER) Israel Start-Up Nation

General Classification

1 Caleb Ewan (AUS) Lotto Soudal 07:47:19

2 Sam Bennett (IRL) Deceuninck-QuickStep 00:00:12

3 Arnaud Demare (FRA) Groupama-FDJ 00:00:16

4 Nikolai Cherkasov (RUS) Gazprom-Rusvelo 00:00:17

5 Alexey Lutsensko (KAZ) Astana Pro Team 00:00:19

SPECS

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%202-litre%204-cylinder%20turbo%20and%203.6-litre%20V6%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESeven-speed%20automatic%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20235hp%20and%20310hp%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E258Nm%20and%20271Nm%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20From%20Dh185%2C100%0D%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

MATCH INFO

Uefa Champions League semi-final, first leg

Bayern Munich v Real Madrid

When: April 25, 10.45pm kick-off (UAE)

Where: Allianz Arena, Munich

Live: BeIN Sports HD

Second leg: May 1, Santiago Bernabeu, Madrid

Credit Score explained

What is a credit score?

In the UAE your credit score is a number generated by the Al Etihad Credit Bureau (AECB), which represents your credit worthiness – in other words, your risk of defaulting on any debt repayments. In this country, the number is between 300 and 900. A low score indicates a higher risk of default, while a high score indicates you are a lower risk.

Why is it important?

Financial institutions will use it to decide whether or not you are a credit risk. Those with better scores may also receive preferential interest rates or terms on products such as loans, credit cards and mortgages.

How is it calculated?

The AECB collects information on your payment behaviour from banks as well as utilitiy and telecoms providers.

How can I improve my score?

By paying your bills on time and not missing any repayments, particularly your loan, credit card and mortgage payments. It is also wise to limit the number of credit card and loan applications you make and to reduce your outstanding balances.

How do I know if my score is low or high?

By checking it. Visit one of AECB’s Customer Happiness Centres with an original and valid Emirates ID, passport copy and valid email address. Liv. customers can also access the score directly from the banking app.

How much does it cost?

A credit report costs Dh100 while a report with the score included costs Dh150. Those only wanting the credit score pay Dh60. VAT is payable on top.

The five pillars of Islam

1. Fasting

2. Prayer

3. Hajj

4. Shahada

5. Zakat

Tonight's Chat on The National

Tonight's Chat is a series of online conversations on The National. The series features a diverse range of celebrities, politicians and business leaders from around the Arab world.

Tonight’s Chat host Ricardo Karam is a renowned author and broadcaster with a decades-long career in TV. He has previously interviewed Bill Gates, Carlos Ghosn, Andre Agassi and the late Zaha Hadid, among others. Karam is also the founder of Takreem.

Intellectually curious and thought-provoking, Tonight’s Chat moves the conversation forward.

Facebook | Our website | Instagram

Frida%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ECarla%20Gutierrez%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarring%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Frida%20Kahlo%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The%20specs%3A%202024%20Mercedes%20E200

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2.0-litre%20four-cyl%20turbo%20%2B%20mild%20hybrid%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E204hp%20at%205%2C800rpm%20%2B23hp%20hybrid%20boost%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E320Nm%20at%201%2C800rpm%20%2B205Nm%20hybrid%20boost%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E9-speed%20auto%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFuel%20consumption%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E7.3L%2F100km%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EOn%20sale%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENovember%2FDecember%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFrom%20Dh205%2C000%20(estimate)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Company%20profile

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EName%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20WallyGPT%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2014%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESaeid%20and%20Sami%20Hejazi%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dubai%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EFinTech%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestment%20raised%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%247.1%20million%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ENumber%20of%20staff%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2020%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestment%20stage%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EPre-seed%20round%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

if you go

The flights

Etihad and Emirates fly direct to Kolkata from Dh1,504 and Dh1,450 return including taxes, respectively. The flight takes four hours 30 minutes outbound and 5 hours 30 minute returning.

The trains

Numerous trains link Kolkata and Murshidabad but the daily early morning Hazarduari Express (3’ 52”) is the fastest and most convenient; this service also stops in Plassey. The return train departs Murshidabad late afternoon. Though just about feasible as a day trip, staying overnight is recommended.

The hotels

Mursidabad’s hotels are less than modest but Berhampore, 11km south, offers more accommodation and facilities (and the Hazarduari Express also pauses here). Try Hotel The Fame, with an array of rooms from doubles at Rs1,596/Dh90 to a ‘grand presidential suite’ at Rs7,854/Dh443.

UAE rugby season

FIXTURES

West Asia Premiership

Dubai Hurricanes v Dubai Knights Eagles

Dubai Tigers v Bahrain

Jebel Ali Dragons v Abu Dhabi Harlequins

UAE Division 1

Dubai Sharks v Dubai Hurricanes II

Al Ain Amblers v Dubai Knights Eagles II

Dubai Tigers II v Abu Dhabi Saracens

Jebel Ali Dragons II v Abu Dhabi Harlequins II

Sharjah Wanderers v Dubai Exiles II

LAST SEASON

West Asia Premiership

Winners – Bahrain

Runners-up – Dubai Exiles

UAE Premiership

Winners – Abu Dhabi Harlequins

Runners-up – Jebel Ali Dragons

Dubai Rugby Sevens

Winners – Dubai Hurricanes

Runners-up – Abu Dhabi Harlequins

UAE Conference

Winners – Dubai Tigers

Runners-up – Al Ain Amblers

Recent winners

2002 Giselle Khoury (Colombia)

2004 Nathalie Nasralla (France)

2005 Catherine Abboud (Oceania)

2007 Grace Bijjani (Mexico)

2008 Carina El-Keddissi (Brazil)

2009 Sara Mansour (Brazil)

2010 Daniella Rahme (Australia)

2011 Maria Farah (Canada)

2012 Cynthia Moukarzel (Kuwait)

2013 Layla Yarak (Australia)

2014 Lia Saad (UAE)

2015 Cynthia Farah (Australia)

2016 Yosmely Massaad (Venezuela)

2017 Dima Safi (Ivory Coast)

2018 Rachel Younan (Australia)

Greatest of All Time

Starring: Vijay, Sneha, Prashanth, Prabhu Deva, Mohan

Formula Middle East Calendar (Formula Regional and Formula 4)

Round 1: January 17-19, Yas Marina Circuit – Abu Dhabi

Round 2: January 22-23, Yas Marina Circuit – Abu Dhabi

Round 3: February 7-9, Dubai Autodrome – Dubai

Round 4: February 14-16, Yas Marina Circuit – Abu Dhabi

Round 5: February 25-27, Jeddah Corniche Circuit – Saudi Arabia