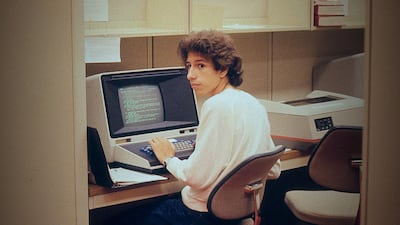

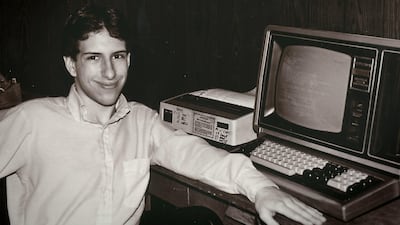

In the early 1980s, 17-year-old Neal Patrick gained worldwide fame – or infamy – for bringing cyber crime and computer hackers into the public consciousness. Shortly after, he dropped out of the spotlight.

These days, hacking is more widely practised, and its threats have grown. The World Economic Forum estimates show the financial costs from cyber crimes are now at least $10.5 trillion annually.

In an interview with The National, Mr Patrick said despite the rapid rise of the hacking and the seemingly unstoppable technological world that made him famous, he lost interest in computers.

"There was so much of a negative impact that I had from it that it made me less interested," he said.

These days, Mr Patrick does marketing and customer analytics for L’Occitane Group. Successful and happy in his chosen profession, his days are very different from the media wave he rode in 1983.

That is when he and some friends, brought together through a shared affinity for computers, hacked into the systems of about 60 businesses and government entities in the US and Canada.

Mr Patrick and his friends called themselves the 414s, based on the area code of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where they lived and went to school.

Computers were not quite a common household item in the 1980s, but his parents bought him a Radio Shack TRS-80.

"They ended up getting one for me to kind of keep me out of trouble and keep me occupied," Mr Patrick said.

He and his fellow 414s took advantage of their modems and learnt from each other how to use early networks such as Telenet to communicate and map out computer users across the US and North America.

Although hardly impressive by today's standards, the early network of computers they were able to identify piqued the interest of the 414s, who soon found out that big businesses and government agencies did not seem too worried about their systems being compromised.

Mr Patrick said that, at the time, because so few thought computers could be compromised, those setting up networks would often use simple passwords such as "test", "password" and "1234".

He said some would even leak passwords or provide hints on electronic bulletin boards used by the earliest PC users.

The 414s were thus able to access networks for large banks, hospitals, cancer research centres and even the Los Alamos National Laboratory, a critically important federal laboratory often used for military research.

What Mr Patrick and the 414s did not realise at the time, however, was that at some of those locations they hacked, administrators were aware something was wrong – and eventually, the FBI came knocking at Mr Patrick's door.

He credits his father, who briefly served time in the juvenile criminal system, for quickly hiring a lawyer, who used Mr Patrick's age to avoid federal charges.

"It was decided that I was going to be the one to speak, do media and interview with reporters if needed," he recalled.

At that time, a movie about computer hackers, War Games starring Matthew Broderick, was in theatres. That, combined with the novelty and mild fear of computers, made Mr Patrick and the 414s' crimes fascinating to the public.

He was soon flying to New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and elsewhere to talk about what he did, and how and why.

"So I remember doing Good Morning America, CBS, The Today Show, then CNN, which had a new show called Crossfire, and then later on did something else again with CBS," Mr Patrick said.

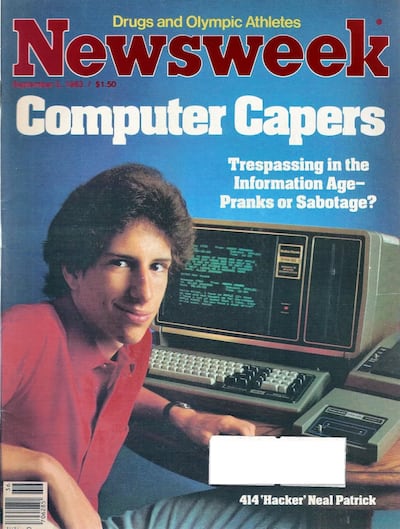

Amid the media blitz and seemingly non-stop phone interviews, someone pointed out to him that his picture was on the newsstands, with a cover story by Newsweek.

"You know, I was young and having to talk so much in public and meet with so many people, reporters and lawyers, that's not my style," he said.

Lingering in the background was the possible legal consequences that he and the 414s might face.

It all culminated in what Mr Patrick said was the most stressful but memorable part of the experience: having to testify before a US congressional committee on Capitol Hill.

Although the situation was serious, his responses to members of Congress elicited a few laughs.

"I realised I was doing something wrong when the FBI showed up," Mr Patrick said during testimony in 1983.

In the months and years that followed his appearance in Washington, Congress passed a series of hacker, cyber-crime and cyber-security laws, many of which are still on the books, including the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

In recent years, the CFAA has come under criticism for being too broad, lacking nuance and having disproportionately high penalties.

Some charged under it may be barred from computer use for significant periods of time, which is much more difficult in 2025 than it was in the late 1980s.

Regardless, because so few computer hacking laws existed in 1983, Mr Patrick did not face any consequences, and his friends received minor fines and probation.

He says that although they were able to gain access to many of the systems they hacked, reports of what they did and what they might have done were wildly exaggerated.

"We didn't take any money and I recall that maybe there were some billing records we destroyed, but that's about it," Mr Patrick said.

He said there was never any serious danger caused, but he understands the concerns of the time.

"It was one of those things where if somebody broke into your computer, even though it's not something dangerous, it's still yours and potentially your stuff there. I get it," he said.

Mr Patrick said he was happy to have walked away from it all unscathed, and is still surprised when it's brought up, as it was in the popular AMC show Halt and Catch Fire, which portrays the technology scene in the '80s and '90s.

In one of the episodes, a character can be seen reading the Newsweek issue featuring him on the cover.

"It comes up every once in a while, and all my co-workers know about it," he said.

To this day, whenever Mr Patrick uses a password for any of his devices, he reminisces about 1983.

"I get frustrated, too – how many passwords do I want to remember?" he said. "But picking a good password doesn't take a lot of effort and will definitely make you less of a target."