For decades, the rhythmic click-clack and metallic slide of a carriage united offices, courtrooms and newsrooms everywhere. When computers took over, the typewriter was relegated to nostalgia – it was a relic of another age. Yet, the machine that once symbolised modernity, has returned as a quiet rebellion against speed, distraction and the digital blur.

Across continents, typewriters are being dusted off, repaired and used once more. Repair shops are reopening, “type-ins” are being organised, and younger artists and writers are rediscovering the thrill of pressing inked keys to paper. What the digital world tried to replace has become its most surprising antidote.

The story began in 1868, when Christopher Latham Sholes patented the first typewriter in Milwaukee and devised the QWERTY layout we still use today. Within decades, the machine transformed how people worked and communicated. By the early 1900s, typewriters were fixtures in homes and offices; by the 1980s, they had grown into a billion-dollar global industry.

In India, the typewriter became a symbol of aspiration. Typing institutes sprouted across cities, producing clerks and stenographers for government offices and courts. Even after computers arrived, the click of metal keys echoed through legal corridors and small-town shops well into the 2010s. When Godrej & Boyce, the country’s last manufacturer, rolled out its final typewriter in 2011, it felt like the end of an era.

Now, a new generation is discovering what earlier ones once took for granted – that typing on paper can be meditative, even defiant. In an age of touchscreens and cloud documents, the typewriter’s appeal lies in its simplicity. It’s nostalgia for some, focus for others and freedom from the constant buzz of notifications for everyone.

“Typewriters slow you down,” says Theodore Munk, founder of The Typewriter Database. “They make you think before you write, and once you do – it’s there forever.”

Writers have long been faithful to the machine. Twain claimed The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was the first typewritten novel – though Life on the Mississippi (1883) later took that honour. Danielle Steel still writes her first drafts on a 1946 Olympia, calling it “an old friend who never lets me down". Tom Hanks, perhaps the world’s most famous collector, owns more than a 100 typewriters and even wrote a book of stories inspired by them. “Every time you type something on a typewriter,” he once said, “It’s a one-of-a-kind work of art.”

But the revival isn’t limited to writers. Teenagers and twenty-somethings who grew up entirely online are now seeking something tangible. In Dubai, Ali Baig, 13, treasures his 1973 Brother Valiant and often uses it for homework. “It feels better… real,” he says. “I like hearing the keys.”

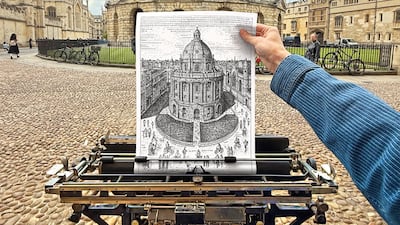

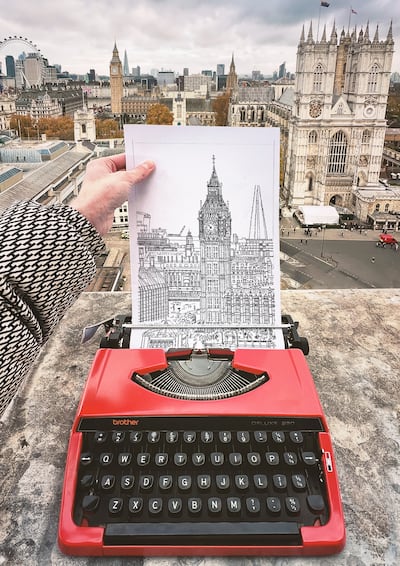

A growing analogue community has helped fuel the trend. Typewriters now trade hands through online groups devoted to vinyl, fountain pens and film photography – linked by a shared longing for texture and tactility. In London, James Cook, 28, uses them to create intricate architectural drawings made entirely of letters and symbols. “There’s a rhythm and tactility to it that feels almost musical,” he says. “No electricity, no software, no undo button – just me and the machine.”

Repairers are also busier than ever. In the UK, Walid and Joujou of Mr & Mrs Vintage Typewriters have restored thousands of machines over the past decade for writers, collectors and families. They’ve watched interest soar, driven by what they call “a craving for authenticity and quiet”. Every restoration, they say, reconnects people with a simpler kind of creativity – one free of pop-ups, alerts and constant interruption.

In India, the revival carries a different texture – part nostalgia, part continuity. Mumbai’s Abhyankar Typing and Shorthand Institute, which has trained typists for more than 85 years, still attracts students long after typing exams were scrapped. Rohini Moholkar, whose grandfather Vithalrao Abhyankar started what was once the first shorthand and typing institute in Asia, was astonished to find it still running when she visited a few years ago.

“My grandfather sold it to Ashok Abhyankar, a relative, and it seems like the institute has withstood the ravages of the electronic typewriter, dictation and computer era. They still teach typing and shorthand there – on old-style typewriters with the clickety-clack of the keys and the whir of the rollers as you push the carriage to the left,” she says.

Classes are still held inside a typical Mumbai chawl, a crowded residential block where time appears to have paused. “It feels like you’ve gone back 70 years,” Moholkar says. “The furniture is original, the stools were commissioned by my grandfather and even the sounds and smells are a throwback.”

In the book, With Great Truth and Regard – The Story of the Typewriter in India by Siddharth Bhatia, Abhyankar is quoted as saying that the institute today houses 45 machines and 250 students. “It’s all about the sound, feel and touch of the keyboard – the bounce of the keys gives a certain pleasure, one that’s not available on a computer.”

Elsewhere in India, the passion continues. In Bengaluru, Sowmya Hiremath, who teaches at Sri Sharadamba Institute of Typing, Shorthand and Computer, says young people often sign up because they want to learn discipline. “Typing teaches focus, accuracy and patience – qualities that never go out of fashion.”

Machines once destined for scrap are being refurbished for collectors, writers and film sets. In Delhi’s narrow lanes, repairmen who once serviced Remington and Godrej models for government offices now find customers among artists and entrepreneurs. “Computers may crash, but a typewriter will work as long as you oil it and respect it,” says Arshad Amin, a technician who has spent four decades at his craft.

Beyond nostalgia, the typewriter’s return reflects a craving for permanence and presence. In an era of instant messaging and editable documents, the typewriter’s clunkiness feels grounding.

In The Distraction-Free First Draft, writer Woz Delgado Flint listed the typewriter’s virtues: no software updates, no notifications, no power cords. “It’s always charged, never crashes and demands you stay present,” she wrote. That single-purpose drive is what many creatives now want.

Ironically, social media has helped fuel the revival. Hashtags such as #typewriter, #analogwriting and #clickclacktherapy have gained millions of views on TikTok and Instagram, where creators share restored machines, typed poems and ASMR-style videos of the keys at work. For digital natives, the typewriter isn’t regression; it’s resistance, a way to make creation slower, more intentional and satisfyingly real.

Still, the movement remains what Cook calls “a quiet but persistent corner of the creative world”. At exhibitions, he often sees children drawn first to the machines. “Many of them think typewriters were invented for art,” he laughs. “They can’t imagine people once used these for office work.”

Perhaps that’s the point. What began as an industrial tool has evolved into a symbolic statement about slowness and intention. As Tom Hanks once wrote in a love letter to his collection, “You can’t duplicate what you get from these things. Each one has a personality, a history, a sound.”

That rhythmic sound of the keys is more than nostalgia. It’s the sound of focus in a distracted age. Cook believes the typewriter isn’t a relic, but a reminder that creativity thrives when technology steps out of the way.

“People are increasingly craving tactile, hands-on experiences,” he says. “And the typewriter fits perfectly into that movement toward slowing down and reconnecting with analogue processes.”