"Do more experiments on babies" sounds like a dystopian slogan, a tagline for a brave new world, but it has been under way for at least 30 years. Undoubtedly it is a good thing. Since the late 1970s, scientific research on babies has provided remarkable insights into how the world's greatest learning apparatus works. After millennia of philosophising by great minds from Plato to Descartes to Freud, the mysteries and wonders of the infant mind are finally being unravelled according to practical, scientific methods.

Take, for instance, the revelation that very young babies regularly perform statistical analysis, such as discerning patterns from a babble of apparently meaningless syllables. At even a few months old, the brain is already computing complicated things that we as adults would perhaps not even know the precise definitions of. Babies are performing Bayesian reasoning and conditional probabilities at the same time as all that jabbering and twittering and screaming. Not only can they determine patterns using mathematical processes, but babies can infer wider systems of behaviour from them. In other words, they can use this analysis to predict how various things in the world will work.

Struggling to dress Astrid or chasing her around the apartment trying to get her to sit at the table at mealtimes, I feel sympathy and admiration for scientists who can conduct any form of meaningful research on babies. After all, babies are not as pliant as a lab rat nor as co-operative as an adult volunteer. They cannot speak. They do not follow simple instructions. So how do these experiments work?

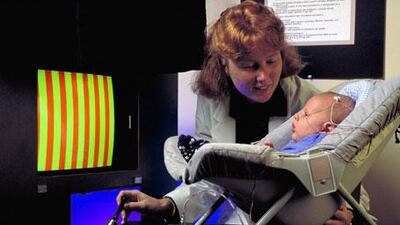

One method was discovered in the 1960s by a psychologist called Robert Fantz. He realised that babies get bored. Show a baby something that conforms to their expectations and sooner or later his or her gaze will wander. Show a baby something that astonishes or surprises them and he or she will peer more intently. Scientists have been using findings such as this one to develop techniques and tools to gain insights into the workings of the infant brain. The results of this body of research have changed our understanding of how the brain works and even a superficial understanding of these findings can help parents with the enigma that is their child. For example, the milestones of infant development - seeing, hearing, sitting, standing, walking - are now known to be linked to biological changes in the brain. They occur according to a genetic blueprint, which experience can do little to alter. Once I grasped that idea, any worries about when Astrid would start to walk melted away. She has her own timetable and there is little point in trying to hurry her along.

One of the most interesting revelations was that much of what makes us human comes not simply from our ability to learn about the world quickly and efficiently, but from our power to imagine other possible worlds. The intense imaginations of children and their ability to realise imaginary worlds so richly plays a vital role in cognitive development. As Alison Gopnik, a psychologist at Berkeley, puts it: "Children aren't confused about fantasy and imagination and reality, which is what psychologists from Freud to Piaget had thought before. They know the difference between imagination and reality really well. It's just they'd rather live in imaginary worlds than in real ones." Children may be remarkable learners, but it is this ability to conjure other possible realms that truly makes us human.

Astrid struck up her first conversation with a stranger recently. Early one morning we were prowling the damp and foggy streets of our neighbourhood. Astrid had been very quiet for many minutes. Motion can induce a kind of stupor in her, where she zones out and switches off for a rare moment or two. So it was surprising when a woman walked by us and Astrid said "Hi". The syllable was clear and loud. Its purpose was emphasised by the lack of any other sounds around it. Clearly it was intended as a greeting.

The woman was dressed in a dark blue uniform and though she was clearly in a hurry striding to work, she instinctively replied with a "Hi". She smiled and Astrid smiled back before we continued on our way. It was an interesting moment, when a different context makes you realise just how much Astrid understands. For years to come, we will be drumming in to her that she should not talk to strangers, but this case was an exception.