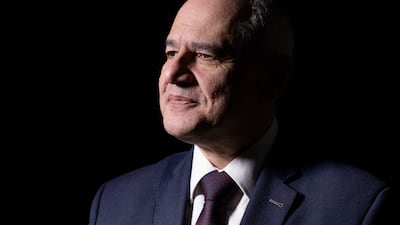

For more than 400 nights, Lebanese MP Melhem Khalaf has slept in the same place. Not at his home but in the country's Parliament, in a protest aimed at his fellow MPs over their failure to end the presidential vacuum that began on November 1, 2022.

The bitterly divided 128-seat legislature, comprised mainly of MPs from historic parties long accused of protecting their own interests, has failed on 12 occasions to elect a successor to Michel Aoun.

The impasse is such that the assembly has not even met to vote since last June, with no resolution in sight.

"It's against our national dignity, it's against our people who made trust in our decisions," Mr Khalaf said from the parliament building in Beirut. "It's our duty, it's our responsibility."

A lawyer and former head of the Beirut Bar Association, Mr Khalaf has argued that – according to Article 74 of the Lebanese constitution – parliament should be convened immediately to elect a president in the event of a vacuum. And yet, more than 500 days on, while some parliamentary business has continued, the presidential palace in Baabda remains vacant.

"We don't have a state, it's a coup d'etat. We have made a suspension of the constitution. Nobody asked about the constitution," he said in an increasingly exasperated tone.

"How can you manage the state when you have no legal reference?"

In the event of a presidential vacuum, the government is meant to take on the powers of the head of state. But Prime Minister Najib Mikati's government is in caretaker status and so is severely deprived of powers.

Further complicating the situation is a war in the south of the country between Lebanese armed groups, mainly Iran-backed Hezbollah, and Israel.

Typically, presidential elections in Lebanon are long, drawn-out affairs, ended only by a series of backdoor deals between the main parties.

In Lebanon's unique confessional system, the role of president is reserved for a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni and the parliamentary speaker a Shiite.

The impasse over the presidential election is not without precedent – it took 46 sessions for Mr Aoun to eventually take office in 2016 – but the situation today is far more severe.

While Lebanese and international efforts continue in a bid to end the stand-off, Mr Khalaf points out that the constitution says parliament should be meeting in a singular open-ended immediate session until a president is elected.

Mr Khalaf is part of a new generation of MPs, some of whom have joined his sit-in, who were elected in 2022 and are affiliated with the 2019 protest movement against Lebanon’s ruling classes that led to the collapse of the government.

And while his mission is for Lebanon, it is also one of personal conscience.

"It's a cause, it's something for me and why the people elected me," he said. "It's how to serve my people. What is my duty? What I have to do, I have to do from my conscience.

"My principal activity is to save the country, to save my people, to save democracy in Lebanon. We are losing our democracy. For this reason I'm fighting, I'm here inside the parliament to say, 'No, we have to have this is a state of law, to respect the rule of law'."

Against the old elite

Mr Khalaf and his allies are challenging an entrenched system that has effectively held power for decades and been held responsible for a succession of crises to afflict Lebanon.

An economic crisis stemming from 2019, one of the worst in modern history, has been blamed on decades of corruption and mismanagement by the ruling elite.

Those same echelons have also been held responsible for the deadly 2020 Beirut blast that killed more than 200 people, injured thousands and destroyed a large part of the Lebanese capital, through gross negligence after several thousand tonnes of highly volatile fertiliser was poorly stored in port depots.

"What we are seeing is people who are in power and they manage their own interest," Mr Khalaf said. "Nobody asked about the national interest. This is the real problem.

"All of these traditional politicians ... they make a silent agreement. They are here just to share power, not to build a nation. When you are an MP, you are an MP of the nation.

"Article 27 of the constitution says the MP is a representative of all the nation. How many of them understand this article?"

But despite the dire situation in Lebanon and the presidential vacancy, Mr Khalaf insists he still has hope.

"Of course, to make hope for our future generations. I am here because I have a hope, I have to create. We have the responsibility for the new generation to give them hope.

"I am fighting for democracy, for human rights, for freedom, justice. I am doing what the constitution imposed on me. All the MPs should be here. All of them should be here since November 1, 2022. They should be here to elect a president."