On a December evening in the Cuban city of Trinidad, near the country's south coast, the temperature – warm, but not too hot or muggy – is about perfect.

After a busy day seeing the sights or visiting a nearby national park area, many tourists will enjoy relaxing in a chair and gazing towards the beach a few miles away. However, if staying in a casa particular, a private house that rents out rooms, they may have to spend the evening in the dark, because Cuba experiences repeated power cuts, often lasting for hours.

While the town’s evening quiet is broken by the buzz of generators switched on by restaurants or hotels to keep things functioning, casa owners will pass guests camping lamps to use in place of non-functioning ceiling lights.

It is far from ideal for a tourism-dependent nation already facing a squeeze on visitor numbers because of the effects of a long-standing US embargo. This was brought in when communists deposed the American-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959 and was tightened under Donald Trump’s first US presidential administration.

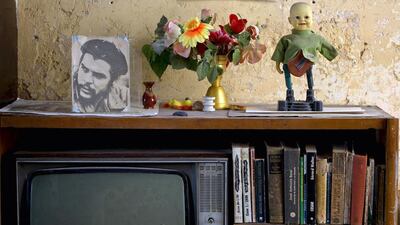

Power shortages exist across the nation, including in other key tourist cities such as Vinales in the far west, Cienfuegos in the south, Santa Clara (celebrated for guerrilla leader Che Guevera’s decisive role there in the revolution) and the capital, Havana. Sometimes, power may be on only for a few hours per day.

One hostel owner in Old Havana, the capital’s partly-restored tourist hotspot, said that there used to be “a lot of tourists” but the situation now was “very, very difficult”.

“In Havana you have around five hours of broken electricity. In Trinidad, in Vinales it’s more complicated,” the hostel owner, who asked for anonymity due to political sensitivities, told The National. His central location means that there are guests in his hostel “all the time”, but owners of other premises are, he said, finding it harder to attract holidaymakers.

Downturn

Indeed, Cuba is the Caribbean country where tourism has most struggled to bounce back from the Covid-19 downturn, according to Dr Emily Morris, honorary senior research fellow at University College London’s Institute of the Americas.

“The depressed tourism numbers – currently around half the pre-Covid level thanks to US sanctions – and foreign exchange shortages affect the quality of the hotels and facilities in general, with missing repairs,” she said. “And the fall in the value of real Cuban salaries since 2021 has had a serious effect on staff levels and morale, and therefore on behaviour. All this is reflected in reviews.”

Power struggles

Whether it is in national parks visited on day trips from Trinidad, or casas in Vinales, there are some holidaymakers present, but tour guides and property owners say fewer than they would have expected for what is peak season in Cuba.

Dr Helen Yaffe, senior lecturer in political and international studies at the University of Glasgow in the UK and the author of We Are Cuba!: How a Revolutionary People Have Survived in a Post-Soviet World, said that "a confluence of different issues" were behind the power shortages, which saw a nationwide blackout in October that lasted several days.

She said that US sanctions were key, as they, for example, limit Cuba’s ability to access credit from international banks, restrict the sale to Cuba of equipment with US components and make it difficult for Cuba to source fuel (some deliveries have been cancelled because suppliers fear US sanctions). Fuel shortages affect power generation, since most electricity is generated from oil. Cuba, Dr Yaffe said, “has no lender of last resort”.

Dr Morris said, however, that in recent months the country appeared to have reduced its vulnerability to national power cut, as shown by a rapid recovery from a power cut at the end of November.

At the end of his first term as US president, Donald Trump designated Cuba a state sponsor of terrorism, which further discouraged visitors from travelling to the Caribbean nation, as doing so renders them ineligible to subsequently visit the US on the country’s visa-waiver scheme.

The hostile relationship between Washington DC and Havana is a far cry from the situation in pre-revolutionary Cuba when, to quote a 1929 travel book, Terry’s Guide to Cuba, “the present-day Cuban is rapidly becoming Americanised”.

“Thousands act, think, talk and look like Americans; wear American clothes, ride in American autos; use American furniture and machinery; oftentimes send their children to American colleges; live for a time in the States themselves or expect to, and eat much American food,” the book stated.

American cars are still seen on Cuban roads, but these are supersized early 1950s Chevrolets, Buicks, Pontiacs and Oldsmobiles imported before the embargo.

Falling numbers

Today, the country has shortages of even basic medicines, and faces an continuing exodus of citizens exhausted by its economic crisis and lack of prospects. According to forecasts published by the World Health Organisation, the population, currently around 11 million, could fall to 9.4 million by 2050. To the casual visitor, the economic challenges and lack of development are obvious, from the severely dilapidated apartment blocks, including in Havana, to the way that many shops consist simply of residents selling a small selection of items from their front room.

In towns, people often travel on horse-drawn carts rather than in motor vehicles, while in the countryside, ploughs pulled by pairs of oxen instead of tractors are a common sight. Motorways connecting major cities are eerily quiet. But the country, under the presidency of Miguel Díaz-Canel, who took over in 2019 from Raúl Castro (who had succeeded his brother Fidel) is aiming to strengthen its energy independence, which would significantly help with the power situation.

Cuba plans to ramp up its solar power capacity, often through Chinese suppliers, which should stabilise its electricity supply and help the country meet climate goals. The aim is that by 2030 almost a quarter of the nation’s energy will come from renewable sources.

“They’ve really accelerated it now,” Dr Morris said. “It was 95 per cent run on fossil fuels, their electricity grid. It’s already coming down to 90 per cent. They’ve got ambitious targets which people looked at and thought, ‘They’re never going to make it.’ Now that it’s such a priority I think they will.”

This greater priority given to the energy transition could, Dr Morris said, lead to a strengthening of ties between Cuba and countries, such as China, that the US is antagonistic towards.

The deep freeze in relations between the US and Cuba has previously improved, notably during the administration of Barack Obama, but the coming years seem likely to be particularly difficult. Mr Trump has nominated as secretary of state Marco Rubio, a Cuban-American senator (his parents immigrated to the US from Cuba) who is a fierce opponent of the regime in Havana.

"They're bracing themselves for the next Trump administration, which looks particularly ominous because of the nomination of Marco Rubio, who's built his career on attacking the Cuban government and being its worst nightmare," said Dr Yaffe.

The Trump administration may increase the enforcement of measures to block the flow of remittances and travel from the US and Cuba, while using Washington DC’s diplomatic and economic weight to pressure third countries to cut ties.

The US is, Dr Yaffe said, “attempting to create the circumstances where the Cuban people will turn on their own government”. But while younger Cubans – plugged into social media and with greater access to information about life in capitalist nations – may lack the revolutionary fervour of previous generations, there is “no sign the government is close to collapse”.

“The biggest critics internally have left the country,” Dr Yaffe said. “It’s not like Venezuela, where you have millions of opposition activists in the country.”

So, while Cuba may be grappling with power cuts and fuel shortages, and struggling to attract visitors, it seems that there is no sign of another revolution brewing among the dogged population of this Caribbean nation.

The Perfect Couple

Starring: Nicole Kidman, Liev Schreiber, Jack Reynor

Creator: Jenna Lamia

Rating: 3/5

more from Janine di Giovanni

Sreesanth's India bowling career

Tests 27, Wickets 87, Average 37.59, Best 5-40

ODIs 53, Wickets 75, Average 33.44, Best 6-55

T20Is 10, Wickets 7, Average 41.14, Best 2-12

Trump v Khan

2016: Feud begins after Khan criticised Trump’s proposed Muslim travel ban to US

2017: Trump criticises Khan’s ‘no reason to be alarmed’ response to London Bridge terror attacks

2019: Trump calls Khan a “stone cold loser” before first state visit

2019: Trump tweets about “Khan’s Londonistan”, calling him “a national disgrace”

2022: Khan’s office attributes rise in Islamophobic abuse against the major to hostility stoked during Trump’s presidency

July 2025 During a golfing trip to Scotland, Trump calls Khan “a nasty person”

Sept 2025 Trump blames Khan for London’s “stabbings and the dirt and the filth”.

Dec 2025 Trump suggests migrants got Khan elected, calls him a “horrible, vicious, disgusting mayor”

UK’s AI plan

- AI ambassadors such as MIT economist Simon Johnson, Monzo cofounder Tom Blomfield and Google DeepMind’s Raia Hadsell

- £10bn AI growth zone in South Wales to create 5,000 jobs

- £100m of government support for startups building AI hardware products

- £250m to train new AI models

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Eco%20Way%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20December%202023%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounder%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Ivan%20Kroshnyi%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dubai%2C%20UAE%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EIndustry%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Electric%20vehicles%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Bootstrapped%20with%20undisclosed%20funding.%20Looking%20to%20raise%20funds%20from%20outside%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The specs: 2019 BMW i8 Roadster

Price, base: Dh708,750

Engine: 1.5L three-cylinder petrol, plus 11.6 kWh lithium-ion battery

Transmission: Six-speed automatic

Power: 374hp (total)

Torque: 570Nm (total)

Fuel economy, combined: 2.0L / 100km

Surianah's top five jazz artists

Billie Holliday: for the burn and also the way she told stories.

Thelonius Monk: for his earnestness.

Duke Ellington: for his edge and spirituality.

Louis Armstrong: his legacy is undeniable. He is considered as one of the most revolutionary and influential musicians.

Terence Blanchard: very political - a lot of jazz musicians are making protest music right now.

ESSENTIALS

The flights

Emirates, Etihad and Swiss fly direct from the UAE to Zurich from Dh2,855 return, including taxes.

The chalet

Chalet N is currently open in winter only, between now and April 21. During the ski season, starting on December 11, a week’s rental costs from €210,000 (Dh898,431) per week for the whole property, which has 22 beds in total, across six suites, three double rooms and a children’s suite. The price includes all scheduled meals, a week’s ski pass, Wi-Fi, parking, transfers between Munich, Innsbruck or Zurich airports and one 50-minute massage per person. Private ski lessons cost from €360 (Dh1,541) per day. Halal food is available on request.

AUSTRALIA%20SQUAD

%3Cp%3EPat%20Cummins%20(capt)%2C%20Scott%20Boland%2C%20Alex%20Carey%2C%20Cameron%20Green%2C%20Marcus%20Harris%2C%20Josh%20Hazlewood%2C%20Travis%20Head%2C%20Josh%20Inglis%2C%20Usman%20Khawaja%2C%20Marnus%20Labuschagne%2C%20Nathan%20Lyon%2C%20Mitchell%20Marsh%2C%20Todd%20Murphy%2C%20Matthew%20Renshaw%2C%20Steve%20Smith%2C%20Mitchell%20Starc%2C%20David%20Warner%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

%E2%80%98FSO%20Safer%E2%80%99%20-%20a%20ticking%20bomb

%3Cp%3EThe%20%3Cem%3ESafer%3C%2Fem%3E%20has%20been%20moored%20off%20the%20Yemeni%20coast%20of%20Ras%20Issa%20since%201988.%3Cbr%3EThe%20Houthis%20have%20been%20blockading%20UN%20efforts%20to%20inspect%20and%20maintain%20the%20vessel%20since%202015%2C%20when%20the%20war%20between%20the%20group%20and%20the%20Yemen%20government%2C%20backed%20by%20the%20Saudi-led%20coalition%20began.%3Cbr%3ESince%20then%2C%20a%20handful%20of%20people%20acting%20as%20a%20%3Ca%20href%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.ae%2Furl%3Fsa%3Dt%26rct%3Dj%26q%3D%26esrc%3Ds%26source%3Dweb%26cd%3D%26ved%3D2ahUKEwiw2OfUuKr4AhVBuKQKHTTzB7cQFnoECB4QAQ%26url%3Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fwww.thenationalnews.com%252Fworld%252Fmena%252Fyemen-s-floating-bomb-tanker-millions-kept-safe-by-skeleton-crew-1.1104713%26usg%3DAOvVaw0t9FPiRsx7zK7aEYgc65Ad%22%20target%3D%22_self%22%3Eskeleton%20crew%3C%2Fa%3E%2C%20have%20performed%20rudimentary%20maintenance%20work%20to%20keep%20the%20%3Cem%3ESafer%3C%2Fem%3E%20intact.%3Cbr%3EThe%20%3Cem%3ESafer%3C%2Fem%3E%20is%20connected%20to%20a%20pipeline%20from%20the%20oil-rich%20city%20of%20Marib%2C%20and%20was%20once%20a%20hub%20for%20the%20storage%20and%20export%20of%20crude%20oil.%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EThe%20%3Cem%3ESafer%3C%2Fem%3E%E2%80%99s%20environmental%20and%20humanitarian%20impact%20may%20extend%20well%20beyond%20Yemen%2C%20experts%20believe%2C%20into%20the%20surrounding%20waters%20of%20Saudi%20Arabia%2C%20Djibouti%20and%20Eritrea%2C%20impacting%20marine-life%20and%20vital%20infrastructure%20like%20desalination%20plans%20and%20fishing%20ports.%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

Desert Warrior

Starring: Anthony Mackie, Aiysha Hart, Ben Kingsley

Director: Rupert Wyatt

Rating: 3/5

COMPANY PROFILE

Company name: Blah

Started: 2018

Founder: Aliyah Al Abbar and Hend Al Marri

Based: Dubai

Industry: Technology and talent management

Initial investment: Dh20,000

Investors: Self-funded

Total customers: 40

EA Sports FC 26

Publisher: EA Sports

Consoles: PC, PlayStation 4/5, Xbox Series X/S

Rating: 3/5

Ms Yang's top tips for parents new to the UAE

- Join parent networks

- Look beyond school fees

- Keep an open mind

CHATGPT%20ENTERPRISE%20FEATURES

%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Enterprise-grade%20security%20and%20privacy%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Unlimited%20higher-speed%20GPT-4%20access%20with%20no%20caps%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Longer%20context%20windows%20for%20processing%20longer%20inputs%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Advanced%20data%20analysis%20capabilities%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Customisation%20options%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Shareable%20chat%20templates%20that%20companies%20can%20use%20to%20collaborate%20and%20build%20common%20workflows%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Analytics%20dashboard%20for%20usage%20insights%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%E2%80%A2%20Free%20credits%20to%20use%20OpenAI%20APIs%20to%20extend%20OpenAI%20into%20a%20fully-custom%20solution%20for%20enterprises%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

GOLF’S RAHMBO

- 5 wins in 22 months as pro

- Three wins in past 10 starts

- 45 pro starts worldwide: 5 wins, 17 top 5s

- Ranked 551th in world on debut, now No 4 (was No 2 earlier this year)

- 5th player in last 30 years to win 3 European Tour and 2 PGA Tour titles before age 24 (Woods, Garcia, McIlroy, Spieth)

The Vile

Starring: Bdoor Mohammad, Jasem Alkharraz, Iman Tarik, Sarah Taibah

Director: Majid Al Ansari

Rating: 4/5

Jetour T1 specs

Engine: 2-litre turbocharged

Power: 254hp

Torque: 390Nm

Price: From Dh126,000

Available: Now

Skoda Superb Specs

Engine: 2-litre TSI petrol

Power: 190hp

Torque: 320Nm

Price: From Dh147,000

Available: Now

TO%20CATCH%20A%20KILLER

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDamian%20Szifron%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Shailene%20Woodley%2C%20Ben%20Mendelsohn%2C%20Ralph%20Ineson%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%202%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

COMPANY%20PROFILE%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENomad%20Homes%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2020%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EHelen%20Chen%2C%20Damien%20Drap%2C%20and%20Dan%20Piehler%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20UAE%20and%20Europe%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EIndustry%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3A%20PropTech%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFunds%20raised%20so%20far%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20%2444m%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Acrew%20Capital%2C%2001%20Advisors%2C%20HighSage%20Ventures%2C%20Abstract%20Ventures%2C%20Partech%2C%20Precursor%20Ventures%2C%20Potluck%20Ventures%2C%20Knollwood%20and%20several%20undisclosed%20hedge%20funds%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

COMPANY PROFILE

Founders: Alhaan Ahmed, Alyina Ahmed and Maximo Tettamanzi

Total funding: Self funded

The National's picks

4.35pm: Tilal Al Khalediah

5.10pm: Continous

5.45pm: Raging Torrent

6.20pm: West Acre

7pm: Flood Zone

7.40pm: Straight No Chaser

8.15pm: Romantic Warrior

8.50pm: Calandogan

9.30pm: Forever Young

SPECS

%3Cp%3EEngine%3A%20Supercharged%203.5-litre%20V6%0D%3Cbr%3EPower%3A%20400hp%0D%3Cbr%3ETorque%3A%20430Nm%0D%3Cbr%3EOn%20sale%3A%20Now%0D%3Cbr%3EPrice%3A%20From%20Dh450%2C000%0D%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

CABINET%20OF%20CURIOSITIES%20EPISODE%201%3A%20LOT%2036

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EGuillermo%20del%20Toro%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Tim%20Blake%20Nelson%2C%20Sebastian%20Roche%2C%20Elpidia%20Carrillo%3Cbr%3ERating%3A%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A