In March last year, a terminally ill man named Steve Wheeler walked into the office of a green funeral home in the US state of Minnesota and asked for something he knew was illegal.

Mr Wheeler, a social studies teacher, was dying from metastatic cancer and had been thinking about how he would be laid to rest.

“There has got to be something different than dropping this big box in the ground with a body that has all these chemicals and stuff in it," he thought.

After hearing the term “human composting” on a talk show, an intrigued Mr Wheeler began looking into it.

Human composting, also known as natural organic reduction, is the process of turning bodies into nutrient-rich material similar to soil.

A deceased person is typically laid in a cradle surrounded by organic material such as wood chips, alfalfa and straw. That cradle is then placed into a vessel for about 30 days.

Microbes break everything down to the molecular level, resulting in the formation of about one cubic yard of soil, which can be used to enrich conservation land, forests or even gardens.

Many people opt for human composting for environmental reasons, preventing the release of carbon into the atmosphere through traditional cremation or the expanding use of finite land for cemeteries.

Mr Wheeler, however, soon discovered the practice was not available in Minnesota and could only be done in a handful of states at the time. Most notable was Washington, which became the first to legalise natural organic reduction in 2019.

That is also when he met Taelor Johnson.

“I had just been to the first ever body composting conference in Denver,” Ms Johnson told The National. “It was interesting how this all came about for us.”

Ms Johnson, who is vice president and director of communications at Interra Green Burial by Mueller Memorial in Minnesota, met various human composting providers at the conference in March last year.

But she connected best with the team from Return Home, a company based in Auburn, Washington, to the south of Seattle.

“We worked out a process right there for us to be able to bring someone from our care into theirs,” Ms Johnson said.

When Mr Wheeler died at the age of 53, she and her team were able to fulfil his dying wish: transferring his body to Auburn for natural organic reduction.

“He was thrilled,” she said. “It created meaning for his own death to know that some good was going to come out of it.”

Watch - Steve Wheeler talks about human composting

Mr Wheeler’s story is not unique. Many people in the US who opt for natural organic reduction are unable to do it in their home state.

At the time of Mr Wheeler’s death, the practice was legal in seven states: Washington, Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, California, New York and Nevada.

But the law was still waiting to go into effect in many of those or was pending further regulatory approval.

Since then, five states have passed bills legalising natural organic reduction and three of those, including Minnesota, approved it in May.

Ms Johnson and a “ragtag team of people” who were passionate about the subject, including former Minnesota state senator Carolyn Laine, worked to get the bill over the line.

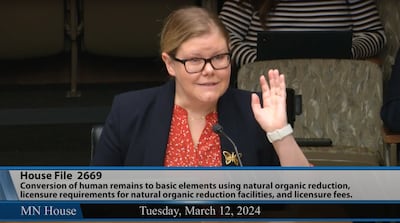

“I got to testify in front of the House and Senate and talk about my experience with Steve,” she said. “It got added to a larger bill in Minnesota and got voted through.”

Licensed providers will be able to offer natural organic reduction in the state from July 1, 2025.

“I think once a state does it and shows that it’s working, it’s a lot easier for other states to follow,” Ms Johnson said.

“The message is often about empowering choice and finding more sustainable ways to help people choose their disposition.”

US Catholic groups have been leading the critical charge against the movement to legalise natural organic reduction and the intricacies of the practice.

The Minnesota Catholic Conference deemed it to be disrespectful to the human body.

“The main experience with composting for most of us is related to household waste such as eggshells and food scraps,” a statement from the organisation reads.

“We toss these unwanted scraps into a container to be broken down by bacteria and then spread around the garden.

"Disposing of human bodies this way goes against our common human desire to respect the dead.”

But Ms Johnson, who has attended laying-in ceremonies including Mr Wheeler's in Washington, described the process as “beautiful and meaningful".

She recounted emotional moments from funerals, one in which grieving family members placed their hands on the vessel of their loved one to feel the warmth being produced by the exothermic process.

“What I think is so revolutionary about this is it creates an extended amount of time to separate from your person’s body,” she said.

“You can literally feel the energy of their body even after they’ve died and the heat slowly taper off over time … it’s a stunning experience for people to say goodbye and let them go.”

First Person

Richard Flanagan

Chatto & Windus

Zayed Sustainability Prize

Classification of skills

A worker is categorised as skilled by the MOHRE based on nine levels given in the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) issued by the International Labour Organisation.

A skilled worker would be someone at a professional level (levels 1 – 5) which includes managers, professionals, technicians and associate professionals, clerical support workers, and service and sales workers.

The worker must also have an attested educational certificate higher than secondary or an equivalent certification, and earn a monthly salary of at least Dh4,000.

COMPANY PROFILE

Founders: Alhaan Ahmed, Alyina Ahmed and Maximo Tettamanzi

Total funding: Self funded

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

RACE CARD

6.30pm: Handicap (Turf) US$175,000 1,000m

7.05pm: Al Bastakiya Trial Conditions (Dirt) $100,000 1,900m

7.40pm: Al Rashidiya Group 2 (T) $250,000 1,800m

8.15pm: Handicap (D) $135,000 2,000m

8.50pm: Al Fahidi Fort Group 2 (T) $250,000 1,400m

9.25pm: Handicap (T) $135,000 2,410m.

GAC GS8 Specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4cyl turbo

Power: 248hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 400Nm at 1,750-4,000rpm

Transmission: 8-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 9.1L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh149,900

Company%20profile

%3Cp%3EName%3A%20Tabby%3Cbr%3EFounded%3A%20August%202019%3B%20platform%20went%20live%20in%20February%202020%3Cbr%3EFounder%2FCEO%3A%20Hosam%20Arab%2C%20co-founder%3A%20Daniil%20Barkalov%3Cbr%3EBased%3A%20Dubai%2C%20UAE%3Cbr%3ESector%3A%20Payments%3Cbr%3ESize%3A%2040-50%20employees%3Cbr%3EStage%3A%20Series%20A%3Cbr%3EInvestors%3A%20Arbor%20Ventures%2C%20Mubadala%20Capital%2C%20Wamda%20Capital%2C%20STV%2C%20Raed%20Ventures%2C%20Global%20Founders%20Capital%2C%20JIMCO%2C%20Global%20Ventures%2C%20Venture%20Souq%2C%20Outliers%20VC%2C%20MSA%20Capital%2C%20HOF%20and%20AB%20Accelerator.%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

UK’s AI plan

- AI ambassadors such as MIT economist Simon Johnson, Monzo cofounder Tom Blomfield and Google DeepMind’s Raia Hadsell

- £10bn AI growth zone in South Wales to create 5,000 jobs

- £100m of government support for startups building AI hardware products

- £250m to train new AI models

Harry%20%26%20Meghan

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ELiz%20Garbus%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Duke%20and%20Duchess%20of%20Sussex%0D%3Cbr%3E%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E3%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The five pillars of Islam

Company%20profile

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EName%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Envi%20Lodges%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESeptember%202021%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ECo-founders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Noelle%20Homsy%20and%20Chris%20Nader%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20UAE%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Hospitality%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ENumber%20of%20employees%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2012%20to%2015%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStage%20of%20investment%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESeries%20A%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Tips for job-seekers

- Do not submit your application through the Easy Apply button on LinkedIn. Employers receive between 600 and 800 replies for each job advert on the platform. If you are the right fit for a job, connect to a relevant person in the company on LinkedIn and send them a direct message.

- Make sure you are an exact fit for the job advertised. If you are an HR manager with five years’ experience in retail and the job requires a similar candidate with five years’ experience in consumer, you should apply. But if you have no experience in HR, do not apply for the job.

David Mackenzie, founder of recruitment agency Mackenzie Jones Middle East

The 12 Syrian entities delisted by UK

Ministry of Interior

Ministry of Defence

General Intelligence Directorate

Air Force Intelligence Agency

Political Security Directorate

Syrian National Security Bureau

Military Intelligence Directorate

Army Supply Bureau

General Organisation of Radio and TV

Al Watan newspaper

Cham Press TV

Sama TV

MATCH INFO

Uefa Champions League, semi-final result:

Liverpool 4-0 Barcelona

Liverpool win 4-3 on aggregate

Champions Legaue final: June 1, Madrid

AI traffic lights to ease congestion at seven points to Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Street

The seven points are:

Shakhbout bin Sultan Street

Dhafeer Street

Hadbat Al Ghubainah Street (outbound)

Salama bint Butti Street

Al Dhafra Street

Rabdan Street

Umm Yifina Street exit (inbound)

The specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4cyl turbo

Power: 261hp at 5,500rpm

Torque: 405Nm at 1,750-3,500rpm

Transmission: 9-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 6.9L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh117,059

More from Neighbourhood Watch

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

Pots for the Asian Qualifiers

Pot 1: Iran, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, China

Pot 2: Iraq, Uzbekistan, Syria, Oman, Lebanon, Kyrgyz Republic, Vietnam, Jordan

Pot 3: Palestine, India, Bahrain, Thailand, Tajikistan, North Korea, Chinese Taipei, Philippines

Pot 4: Turkmenistan, Myanmar, Hong Kong, Yemen, Afghanistan, Maldives, Kuwait, Malaysia

Pot 5: Indonesia, Singapore, Nepal, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Mongolia, Guam, Macau/Sri Lanka

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

Company%20Profile

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Astra%20Tech%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EMarch%202022%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EDubai%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounder%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EAbdallah%20Abu%20Sheikh%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EIndustry%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20technology%20investment%20and%20development%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFunding%20size%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20%24500m%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

How to apply for a drone permit

- Individuals must register on UAE Drone app or website using their UAE Pass

- Add all their personal details, including name, nationality, passport number, Emiratis ID, email and phone number

- Upload the training certificate from a centre accredited by the GCAA

- Submit their request

What are the regulations?

- Fly it within visual line of sight

- Never over populated areas

- Ensure maximum flying height of 400 feet (122 metres) above ground level is not crossed

- Users must avoid flying over restricted areas listed on the UAE Drone app

- Only fly the drone during the day, and never at night

- Should have a live feed of the drone flight

- Drones must weigh 5 kg or less

LA LIGA FIXTURES

Friday Valladolid v Osasuna (Kick-off midnight UAE)

Saturday Valencia v Athletic Bilbao (5pm), Getafe v Sevilla (7.15pm), Huesca v Alaves (9.30pm), Real Madrid v Atletico Madrid (midnight)

Sunday Real Sociedad v Eibar (5pm), Real Betis v Villarreal (7.15pm), Elche v Granada (9.30pm), Barcelona v Levante (midnight)

Monday Celta Vigo v Cadiz (midnight)