When Sudan's army seized power in Khartoum on October 25, many Sudanese worried about a revisit to something like Omar Al Bashir’s tyrannical rule. The hundreds of thousands in the streets protesting against the takeover have rejected the prospect of a minority of army generals and politicians speaking with a loud voice, when media blackouts and internet outages have, in their eyes, muted the majority. And they most fiercely rejected the idea of a tighter concentration of power after toppling an autocrat.

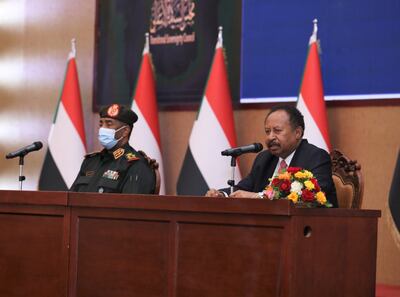

In a televised address on Sunday, Gen Abdel Fattah Al Burhan proposed a solution to the crisis: to reinstate ousted Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok. Gen Al Burhan's intentions seem clear. First, he is reluctant to leave any impression that he rules unilaterally. And second, he wants to emphasise that the military's intervention only occurred because some politicians had earlier tried to hijack the policy-making process, causing the civilian government to drift deeper into animosity and division.

The general's main criticism was reserved for the Forces of Freedom of Change (FFC), the pro-democracy umbrella group that had led the 2019 uprising against Al Bashir and formed Mr Hamdok's power base. Gen Al Burhan and his camp do not believe “coup” is the right word to describe the events of last months. Terminology matters.

The new political agreement between Gen Al Burhan and Mr Hamdok also promises the freedom of all political detainees, and to uphold the earlier commitment to free elections in the future. Most of the international community doesn't want either side or any party to take unilateral steps. Sudan's foreign allies would like both sides to stick to the original political road map agreed in August 2019.

Still, for all of the conciliatory words, there’s no love lost between the army and the protesters. The latter are backed by a cohort of influential political parties coalesced around the FFC alliance, whose main representatives wereconspicuous by their absence from the presidential palace in Khartoum on Sunday. But in any relationship, trust is more important – and harder to come by – than love. And prominent protest movement leaders say they have already trusted the army too much to be let down after two years of what was portrayed in the beginning as an amazing partnership. Many of them now want a permanent divorce.

Yet, some have balked further at the prospect of the return of Mr Hamdok, and rejected his new deal. “This is an insult to the people on the streets. If you trust so much, you will only be deceived, no?” Seddiq Abu Fawwaz, a leading figure at the FFC told me.

But those who do support the new deal see it an historic and wise move from Mr Hamdok, who was a former director at the UN Economic Commission for Africa. In their eyes, this agreement stops the bloodshed and reinforces the fragile stability Sudan has witnessed after decades of international sanctions and financial malaise.

Across the whole of society, however, there is indeed a general air of despondency about the state of democracy in Sudan. Ironically, that common sentiment is derived from the widespread recognition that Sudanese people from different walks of life see the country very differently.

When one talks to politicians and generals, they make Sudan sound very stable, and believe that both the country and the world will move on from the current crisis quickly. Jibril Ibrahim, the Finance Minister, is one of those who propagates this picture, so it is perhaps no surprise that he was one of nine ministers to retained their posts in the aftermath of the military intervention. The minister of urban development, on the other hand, had resigned in protest.

“Some parties in the FFC wanted to negate the army completely,” Mr Ibrahim told me in a recent interview. “This was wrong as it’s part and parcel of society in Sudan. We need a balance of power without excluding anyone from the political and ethnic mosaic of Sudan.”

Interviews with protesters, however, paint an entirely different, much more complex picture.

And despite the fact that Sudan's Sovereign Council, which acts as the country's head of state, is made up of 9 civilians and five military officers, the protesters believe the balance of influence is in favour of the military. The concern is that a revived military-civilian partnership will be weakened by the legacy of the October military takeover.The army insists that its intervention rectified the course of the revolution, and will have to work hard to make that the case.

Gen Al Burhan's task now is to convince Mr Hamdok and his camp that the new deal is the celebration of trust and commitment, and a closure of a chapter of mistrust and misgivings. It will take a big effort to convince many Sudanese of the same.