Can Boris Johnson survive as Britain’s prime minister? If I could reliably predict the future I’d be making a living on horse racing, but I will try to answer that question in a moment. Clearly 2021 is ending disastrously for Mr Johnson. Until now, he has been Britain’s Teflon prime minister. Nothing sticks – not his policy failures, nor what British people have seen of his deceptions and the numerous allegations of dodgy dealings about money, cronyism and patronage. But Teflon Boris has worn thin. So has his comic persona in such serious times, with another wave of coronavirus upon us. One successful prediction that I did make about Mr Johnson was published in The National in October 2020. I wrote that 2019 had been Johnson’s year of great successes in becoming prime minister, leading his party to an 80-seat majority, but by 2021 he would hit the hard brick wall of reality. There would be a series of failures and broken promises. And so it has proved.

More than 146,000 British people have now died with the coronavirus. The Johnson government was slow to react and remains conflicted on what to do. There is a backlash within his own Conservative party against his announcement of new Covid-19 restrictions, despite fears that the National Health Service is near to being overwhelmed.

Then there is Brexit, which despite his boasts, is not “done”. Far from it. Mr Johnson is trying to unpick the deal he negotiated, in a way that has irritated Ireland and much of the EU, and ultimately has ensured that his much-promoted idea of a US-UK trade deal is unlikely to happen with the Biden administration.

He is also at loggerheads with France over asylum seekers. Then there is the botched withdrawal from Afghanistan. The incompetence of the Johnson government has cost the lives of Afghans who tried to help the British against the Taliban. The British economy is under-performing, thanks to Brexit. Taxes are going up. So is inflation. GDP is predicted to underperform by 4 per cent. Promises about building 40 new hospitals and a new high-speed trainline connecting northern English cities have proved to be questionable salesmanship. And almost daily the Johnson administration is mired in allegations of sleaze and lying.

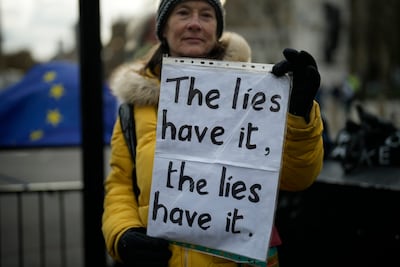

What was not predictable, however, was that the one scandal which would cut through to British voters would involve a Christmas quiz hosted by Johnson at Downing Street. At the informal party, the staff drank alcohol while the rest of the country was under severe coronavirus restrictions, and ordinary citizens who held parties were fined for committing a criminal offence. The recording of Johnson’s staff laughing and joking as they rehearsed how to handle this potential scandal nicknamed “Partygate,” became a worldwide viral sensation. It came as British families mourned their coronavirus dead or restricted their behaviour to obey Mr Johnson’s own government rules.

As a classics scholar, Mr Johnson will know the observation of the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus: “character is destiny”. That is both Johnson’s strength and his likely downfall. He has been able to change his policies, break his promises, promote fantastic schemes for bridges, airports and new hospitals that never get built, and still be popular with voters who never much believed him anyway.

They immediately saw his character as that of a shambolic personality who could break the mould of politics-as-usual, and that was attractive to some. But the other part of Mr Johnson’s character is of someone who sees rules as only for the little people, not for himself, combined with the British Labour party leader Kier Starmer’s characterisation of Mr Johnson as a “trivial” man, incapable of being truly serious in serious times.

Mr Johnson, therefore, looks to be in the twilight of his political career. A special by-election takes place on Thursday in North Shropshire, a rock solid Conservative seat, one of the safest in England. If the Conservatives were to lose there, then Mr Johnson’s key attraction to his party – being a vote winner – will have gone, and so, soon, could he. But assuming his party does retain this North Shropshire seat, Boris Johnson will likely stagger on into 2022, distrusted, and plagued by scandals which will multiply. His Downing Street staff are unlikely to be loyal to a leader who seems to regard those around him as a human shield, to be sacked to save his own career.

If this prediction is correct, then 2022 will begin with Mr Johnson in office but not really in power, wounded and weakened. That may suit Mr Johnson’s opponents in the Labour party, who have been revitalised in recent weeks and who scent blood. A new Conservative leader, a new prime minister, someone more competent and hardworking than Boris Johnson, could quite possibly revive the Conservative party’s fortunes. If Mr Johnson cares about his country or his party then he will go. If he cares only about himself, he will stay. His character suggests he will stay, twisting in the wind.

Our family matters legal consultant

Name: Hassan Mohsen Elhais

Position: legal consultant with Al Rowaad Advocates and Legal Consultants.

MATCH INFO

Manchester United 1 (Rashford 36')

Liverpool 1 (Lallana 84')

Man of the match: Marcus Rashford (Manchester United)

Ten tax points to be aware of in 2026

1. Domestic VAT refund amendments: request your refund within five years

If a business does not apply for the refund on time, they lose their credit.

2. E-invoicing in the UAE

Businesses should continue preparing for the implementation of e-invoicing in the UAE, with 2026 a preparation and transition period ahead of phased mandatory adoption.

3. More tax audits

Tax authorities are increasingly using data already available across multiple filings to identify audit risks.

4. More beneficial VAT and excise tax penalty regime

Tax disputes are expected to become more frequent and more structured, with clearer administrative objection and appeal processes. The UAE has adopted a new penalty regime for VAT and excise disputes, which now mirrors the penalty regime for corporate tax.

5. Greater emphasis on statutory audit

There is a greater need for the accuracy of financial statements. The International Financial Reporting Standards standards need to be strictly adhered to and, as a result, the quality of the audits will need to increase.

6. Further transfer pricing enforcement

Transfer pricing enforcement, which refers to the practice of establishing prices for internal transactions between related entities, is expected to broaden in scope. The UAE will shortly open the possibility to negotiate advance pricing agreements, or essentially rulings for transfer pricing purposes.

7. Limited time periods for audits

Recent amendments also introduce a default five-year limitation period for tax audits and assessments, subject to specific statutory exceptions. While the standard audit and assessment period is five years, this may be extended to up to 15 years in cases involving fraud or tax evasion.

8. Pillar 2 implementation

Many multinational groups will begin to feel the practical effect of the Domestic Minimum Top-Up Tax (DMTT), the UAE's implementation of the OECD’s global minimum tax under Pillar 2. While the rules apply for financial years starting on or after January 1, 2025, it is 2026 that marks the transition to an operational phase.

9. Reduced compliance obligations for imported goods and services

Businesses that apply the reverse-charge mechanism for VAT purposes in the UAE may benefit from reduced compliance obligations.

10. Substance and CbC reporting focus

Tax authorities are expected to continue strengthening the enforcement of economic substance and Country-by-Country (CbC) reporting frameworks. In the UAE, these regimes are increasingly being used as risk-assessment tools, providing tax authorities with a comprehensive view of multinational groups’ global footprints and enabling them to assess whether profits are aligned with real economic activity.

Contributed by Thomas Vanhee and Hend Rashwan, Aurifer

ABU DHABI T10: DAY TWO

Bangla Tigers v Deccan Gladiators (3.30pm)

Delhi Bulls v Karnataka Tuskers (5.45pm)

Northern Warriors v Qalandars (8.00pm)

COMPANY%20PROFILE%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EName%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Haltia.ai%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%202023%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ECo-founders%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Arto%20Bendiken%20and%20Talal%20Thabet%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dubai%2C%20UAE%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EIndustry%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20AI%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ENumber%20of%20employees%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%2041%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFunding%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20About%20%241.7%20million%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Self%2C%20family%20and%20friends%26nbsp%3B%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Who was Alfred Nobel?

The Nobel Prize was created by wealthy Swedish chemist and entrepreneur Alfred Nobel.

- In his will he dictated that the bulk of his estate should be used to fund "prizes to those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind".

- Nobel is best known as the inventor of dynamite, but also wrote poetry and drama and could speak Russian, French, English and German by the age of 17. The five original prize categories reflect the interests closest to his heart.

- Nobel died in 1896 but it took until 1901, following a legal battle over his will, before the first prizes were awarded.

Mercer, the investment consulting arm of US services company Marsh & McLennan, expects its wealth division to at least double its assets under management (AUM) in the Middle East as wealth in the region continues to grow despite economic headwinds, a company official said.

Mercer Wealth, which globally has $160 billion in AUM, plans to boost its AUM in the region to $2-$3bn in the next 2-3 years from the present $1bn, said Yasir AbuShaban, a Dubai-based principal with Mercer Wealth.

“Within the next two to three years, we are looking at reaching $2 to $3 billion as a conservative estimate and we do see an opportunity to do so,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Mercer does not directly make investments, but allocates clients’ money they have discretion to, to professional asset managers. They also provide advice to clients.

“We have buying power. We can negotiate on their (client’s) behalf with asset managers to provide them lower fees than they otherwise would have to get on their own,” he added.

Mercer Wealth’s clients include sovereign wealth funds, family offices, and insurance companies among others.

From its office in Dubai, Mercer also looks after Africa, India and Turkey, where they also see opportunity for growth.

Wealth creation in Middle East and Africa (MEA) grew 8.5 per cent to $8.1 trillion last year from $7.5tn in 2015, higher than last year’s global average of 6 per cent and the second-highest growth in a region after Asia-Pacific which grew 9.9 per cent, according to consultancy Boston Consulting Group (BCG). In the region, where wealth grew just 1.9 per cent in 2015 compared with 2014, a pickup in oil prices has helped in wealth generation.

BCG is forecasting MEA wealth will rise to $12tn by 2021, growing at an annual average of 8 per cent.

Drivers of wealth generation in the region will be split evenly between new wealth creation and growth of performance of existing assets, according to BCG.

Another general trend in the region is clients’ looking for a comprehensive approach to investing, according to Mr AbuShaban.

“Institutional investors or some of the families are seeing a slowdown in the available capital they have to invest and in that sense they are looking at optimizing the way they manage their portfolios and making sure they are not investing haphazardly and different parts of their investment are working together,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Some clients also have a higher appetite for risk, given the low interest-rate environment that does not provide enough yield for some institutional investors. These clients are keen to invest in illiquid assets, such as private equity and infrastructure.

“What we have seen is a desire for higher returns in what has been a low-return environment specifically in various fixed income or bonds,” he said.

“In this environment, we have seen a de facto increase in the risk that clients are taking in things like illiquid investments, private equity investments, infrastructure and private debt, those kind of investments were higher illiquidity results in incrementally higher returns.”

The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, one of the largest sovereign wealth funds, said in its 2016 report that has gradually increased its exposure in direct private equity and private credit transactions, mainly in Asian markets and especially in China and India. The authority’s private equity department focused on structured equities owing to “their defensive characteristics.”

The specs: Aston Martin DB11 V8 vs Ferrari GTC4Lusso T

Price, base: Dh840,000; Dh120,000

Engine: 4.0L V8 twin-turbo; 3.9L V8 turbo

Transmission: Eight-speed automatic; seven-speed automatic

Power: 509hp @ 6,000rpm; 601hp @ 7,500rpm

Torque: 695Nm @ 2,000rpm; 760Nm @ 3,000rpm

Fuel economy, combined: 9.9L / 100km; 11.6L / 100km

Silent Hill f

Publisher: Konami

Platforms: PlayStation 5, Xbox Series X/S, PC

Rating: 4.5/5

The%20specs

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%201.8-litre%204-cyl%20turbo%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E190hp%20at%205%2C200rpm%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20320Nm%20from%201%2C800-5%2C000rpm%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESeven-speed%20dual-clutch%20auto%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFuel%20consumption%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%206.7L%2F100km%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20From%20Dh111%2C195%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EOn%20sale%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENow%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

F1 The Movie

Starring: Brad Pitt, Damson Idris, Kerry Condon, Javier Bardem

Director: Joseph Kosinski

Rating: 4/5

The specs: Macan Turbo

Engine: Dual synchronous electric motors

Power: 639hp

Torque: 1,130Nm

Transmission: Single-speed automatic

Touring range: 591km

Price: From Dh412,500

On sale: Deliveries start in October

HEADLINE HERE

- I would recommend writing out the text in the body

- And then copy into this box

- It can be as long as you link

- But I recommend you use the bullet point function (see red square)

- Or try to keep the word count down

- Be wary of other embeds lengthy fact boxes could crash into

- That's about it

How to keep control of your emotions

If your investment decisions are being dictated by emotions such as fear, greed, hope, frustration and boredom, it is time for a rethink, Chris Beauchamp, chief market analyst at online trading platform IG, says.

Greed

Greedy investors trade beyond their means, open more positions than usual or hold on to positions too long to chase an even greater gain. “All too often, they incur a heavy loss and may even wipe out the profit already made.

Tip: Ignore the short-term hype, noise and froth and invest for the long-term plan, based on sound fundamentals.

Fear

The risk of making a loss can cloud decision-making. “This can cause you to close out a position too early, or miss out on a profit by being too afraid to open a trade,” he says.

Tip: Start with a plan, and stick to it. For added security, consider placing stops to reduce any losses and limits to lock in profits.

Hope

While all traders need hope to start trading, excessive optimism can backfire. Too many traders hold on to a losing trade because they believe that it will reverse its trend and become profitable.

Tip: Set realistic goals. Be happy with what you have earned, rather than frustrated by what you could have earned.

Frustration

Traders can get annoyed when the markets have behaved in unexpected ways and generates losses or fails to deliver anticipated gains.

Tip: Accept in advance that asset price movements are completely unpredictable and you will suffer losses at some point. These can be managed, say, by attaching stops and limits to your trades.

Boredom

Too many investors buy and sell because they want something to do. They are trading as entertainment, rather than in the hope of making money. As well as making bad decisions, the extra dealing charges eat into returns.

Tip: Open an online demo account and get your thrills without risking real money.