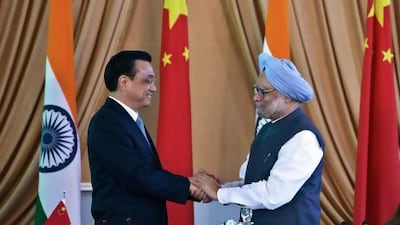

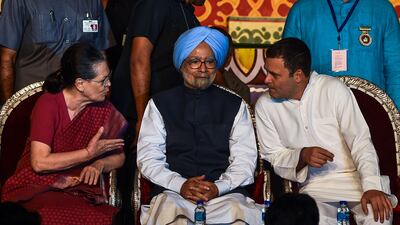

Following the death of Manmohan Singh at the age of 92 on Thursday, one can’t help but wonder whether India will ever have another technocratic prime minister like him. Given the populist turn the country and large parts of the world have taken in recent years, this appears unlikely for the foreseeable future.

The Bharatiya Janata Party-led government in New Delhi and the main opposition party, the Indian National Congress, of which Dr Singh was a long-time member and leader, appear to have embraced overlapping versions of economic populism that will probably have worried the late prime minister even in retirement.

The federal government, under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has undoubtedly maintained fiscal discipline over the past decade. It has instituted some meaningful reforms, like institutionalising a nationwide Goods and Services Tax. But it has baulked at other big-ticket items by walking back much-needed land reforms and later repealing three potentially far-reaching farm laws.

In a surprise move, the government ruled out joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a free-trade agreement that, among others, includes China and the 10 countries that make up the Association of South-East Asian Nations. It was a clear indication that New Delhi was going in the protectionist direction.

But what is more troubling is the enthusiasm shared by almost every Indian political party, particularly in individual states, to deliver a range of direct benefits to the citizens, from farm-loan waivers to cooking gas to free bus travel for women. Some of this welfarism is targeted and even necessary, given that about 129 million Indians continue to live in extreme poverty, but there are genuine concerns that many state governments are spending beyond their means simply to stay in power.

This isn’t unique to India. Many other countries, too, have poured resources into large welfare programmes since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. But a period of austerity that followed the 2007-2008 global financial crisis appears to have been replaced by an era of exploding public debt, expected to exceed $100 trillion at the end of the current year, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Dr Singh would no doubt have been expected to loosen the government purse strings in times of emergency. In fact, he sought government interventions, as long as they were paid for. As prime minister, from 2004 to 2014, he even put in place the makings of a modern welfare state, enacting schemes such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and the Right to Education Act.

As the political scientist Ashutosh Varshney wrote in The Indian Express recently: "Manmohan Singh’s welfarism viewed the underprivileged as rights-bearing citizens, not simply as recipients of largesse."

And yet he was cut from a different philosophical cloth, given his focus on market reforms and fierce conviction that people needed to be given economic freedom. The Economist’s description of Dr Singh as “India’s economic freedom fighter” can hardly be disputed.

In 1991, Dr Singh memorably quoted Victor Hugo, telling his fellow MPs that “no power on Earth can stop an idea whose time has come”. This “idea” was that it was time for India to shed its socialist past and embrace a capitalist future by moving in the direction of liberalisation, globalisation and privatisation.

Over the next five years as finance minister, he worked with the country’s seemingly ossified bureaucracy to ensure that the government could embark on some of the large-scale economic reforms that he envisioned. These included the abolition of most trade licences, inviting foreign investment in the stock market and reconfiguring the banking sector.

Singh’s struggle to deliver prosperity for all is the classic conundrum that today’s moderate politicians around the world also have to contend with

The fruits of his government’s efforts, and those of subsequent administrations, transformed India from a country that faced an acute balance of payments crisis in the late 1980s to becoming the world’s fifth-largest economy. These reforms pulled the country out of its four per cent growth rate to achieve closer to 10 per cent economic expansion on a consistent basis over the following years.

The momentum generated by this “idea” of creating economic freedom proved unstoppable, even decades later; the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative states that more than 270 million people were lifted out of poverty between 2005-06 and 2015-16, a 10-year period during most of which Dr Singh served as prime minister.

However, no historical figure is perfect and Dr Singh has had his critics.

Many on the left have pointed to India’s continuing poverty and a rise in income inequality that his policies engendered over three decades. Many on the economic right have claimed he didn’t do enough, such as pushing through agricultural reforms that today’s government has burnt its fingers in trying to implement.

Dr Singh’s struggle to please all, and more importantly to deliver prosperity for all, is the classic conundrum that today’s moderate, technocratic politicians around the world also have to contend with. As parties become more ideologically extreme, and the spirit of consensus is depleted in a fast-changing world, it could be a while before a post-Cold War historical figure like Dr Singh emerges again, let alone thrives.

Lexus LX700h specs

Engine: 3.4-litre twin-turbo V6 plus supplementary electric motor

Power: 464hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 790Nm from 2,000-3,600rpm

Transmission: 10-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 11.7L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh590,000

WHEN TO GO:

September to November or March to May; this is when visitors are most likely to see what they’ve come for.

WHERE TO STAY:

Meghauli Serai, A Taj Safari - Chitwan National Park resort (tajhotels.com) is a one-hour drive from Bharatpur Airport with stays costing from Dh1,396 per night, including taxes and breakfast. Return airport transfers cost from Dh661.

HOW TO GET THERE:

Etihad Airways regularly flies from Abu Dhabi to Kathmandu from around Dh1,500 per person return, including taxes. Buddha Air (buddhaair.com) and Yeti Airlines (yetiairlines.com) fly from Kathmandu to Bharatpur several times a day from about Dh660 return and the flight takes just 20 minutes. Driving is possible but the roads are hilly which means it will take you five or six hours to travel 148 kilometres.

The finalists

Player of the Century, 2001-2020: Cristiano Ronaldo (Juventus), Lionel Messi (Barcelona), Mohamed Salah (Liverpool), Ronaldinho

Coach of the Century, 2001-2020: Pep Guardiola (Manchester City), Jose Mourinho (Tottenham Hotspur), Zinedine Zidane (Real Madrid), Sir Alex Ferguson

Club of the Century, 2001-2020: Al Ahly (Egypt), Bayern Munich (Germany), Barcelona (Spain), Real Madrid (Spain)

Player of the Year: Cristiano Ronaldo, Lionel Messi, Robert Lewandowski (Bayern Munich)

Club of the Year: Bayern Munich, Liverpool, Real Madrid

Coach of the Year: Gian Piero Gasperini (Atalanta), Hans-Dieter Flick (Bayern Munich), Jurgen Klopp (Liverpool)

Agent of the Century, 2001-2020: Giovanni Branchini, Jorge Mendes, Mino Raiola

Company profile

Name: Thndr

Started: October 2020

Founders: Ahmad Hammouda and Seif Amr

Based: Cairo, Egypt

Sector: FinTech

Initial investment: pre-seed of $800,000

Funding stage: series A; $20 million

Investors: Tiger Global, Beco Capital, Prosus Ventures, Y Combinator, Global Ventures, Abdul Latif Jameel, Endure Capital, 4DX Ventures, Plus VC, Rabacap and MSA Capital

Tenet

Director: Christopher Nolan

Stars: John David Washington, Robert Pattinson, Elizabeth Debicki, Dimple Kapadia, Michael Caine, Kenneth Branagh

Rating: 5/5

The%20end%20of%20Summer

%3Cp%3EAuthor%3A%20Salha%20Al%20Busaidy%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EPages%3A%20316%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EPublisher%3A%20The%20Dreamwork%20Collective%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

GCC-UK%20Growth

%3Cp%3EAn%20FTA%20with%20the%20GCC%20would%20be%20very%20significant%20for%20the%20UK.%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20My%20Department%20has%20forecast%20that%20it%20could%20generate%20an%20additional%20%C2%A31.6%20billion%20a%20year%20for%20our%20economy.%3Cbr%3EWith%20consumer%20demand%20across%20the%20GCC%20predicted%20to%20increase%20to%20%C2%A3800%20billion%20by%202035%20this%20deal%20could%20act%20as%20a%20launchpad%20from%20which%20our%20firms%20can%20boost%20their%20market%20share.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Mercer, the investment consulting arm of US services company Marsh & McLennan, expects its wealth division to at least double its assets under management (AUM) in the Middle East as wealth in the region continues to grow despite economic headwinds, a company official said.

Mercer Wealth, which globally has $160 billion in AUM, plans to boost its AUM in the region to $2-$3bn in the next 2-3 years from the present $1bn, said Yasir AbuShaban, a Dubai-based principal with Mercer Wealth.

“Within the next two to three years, we are looking at reaching $2 to $3 billion as a conservative estimate and we do see an opportunity to do so,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Mercer does not directly make investments, but allocates clients’ money they have discretion to, to professional asset managers. They also provide advice to clients.

“We have buying power. We can negotiate on their (client’s) behalf with asset managers to provide them lower fees than they otherwise would have to get on their own,” he added.

Mercer Wealth’s clients include sovereign wealth funds, family offices, and insurance companies among others.

From its office in Dubai, Mercer also looks after Africa, India and Turkey, where they also see opportunity for growth.

Wealth creation in Middle East and Africa (MEA) grew 8.5 per cent to $8.1 trillion last year from $7.5tn in 2015, higher than last year’s global average of 6 per cent and the second-highest growth in a region after Asia-Pacific which grew 9.9 per cent, according to consultancy Boston Consulting Group (BCG). In the region, where wealth grew just 1.9 per cent in 2015 compared with 2014, a pickup in oil prices has helped in wealth generation.

BCG is forecasting MEA wealth will rise to $12tn by 2021, growing at an annual average of 8 per cent.

Drivers of wealth generation in the region will be split evenly between new wealth creation and growth of performance of existing assets, according to BCG.

Another general trend in the region is clients’ looking for a comprehensive approach to investing, according to Mr AbuShaban.

“Institutional investors or some of the families are seeing a slowdown in the available capital they have to invest and in that sense they are looking at optimizing the way they manage their portfolios and making sure they are not investing haphazardly and different parts of their investment are working together,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Some clients also have a higher appetite for risk, given the low interest-rate environment that does not provide enough yield for some institutional investors. These clients are keen to invest in illiquid assets, such as private equity and infrastructure.

“What we have seen is a desire for higher returns in what has been a low-return environment specifically in various fixed income or bonds,” he said.

“In this environment, we have seen a de facto increase in the risk that clients are taking in things like illiquid investments, private equity investments, infrastructure and private debt, those kind of investments were higher illiquidity results in incrementally higher returns.”

The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, one of the largest sovereign wealth funds, said in its 2016 report that has gradually increased its exposure in direct private equity and private credit transactions, mainly in Asian markets and especially in China and India. The authority’s private equity department focused on structured equities owing to “their defensive characteristics.”

Why it pays to compare

A comparison of sending Dh20,000 from the UAE using two different routes at the same time - the first direct from a UAE bank to a bank in Germany, and the second from the same UAE bank via an online platform to Germany - found key differences in cost and speed. The transfers were both initiated on January 30.

Route 1: bank transfer

The UAE bank charged Dh152.25 for the Dh20,000 transfer. On top of that, their exchange rate margin added a difference of around Dh415, compared with the mid-market rate.

Total cost: Dh567.25 - around 2.9 per cent of the total amount

Total received: €4,670.30

Route 2: online platform

The UAE bank’s charge for sending Dh20,000 to a UK dirham-denominated account was Dh2.10. The exchange rate margin cost was Dh60, plus a Dh12 fee.

Total cost: Dh74.10, around 0.4 per cent of the transaction

Total received: €4,756

The UAE bank transfer was far quicker – around two to three working days, while the online platform took around four to five days, but was considerably cheaper. In the online platform transfer, the funds were also exposed to currency risk during the period it took for them to arrive.

Illegal%20shipments%20intercepted%20in%20Gulf%20region

%3Cp%3EThe%20Royal%20Navy%20raid%20is%20the%20latest%20in%20a%20series%20of%20successful%20interceptions%20of%20drugs%20and%20arms%20in%20the%20Gulf%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMay%2011%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EUS%20coastguard%20recovers%20%2480%20million%20heroin%20haul%20from%20fishing%20vessel%20in%20Gulf%20of%20Oman%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMay%208%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20US%20coastguard%20vessel%20USCGC%20Glen%20Harris%20seizes%20heroin%20and%20meth%20worth%20more%20than%20%2430%20million%20from%20a%20fishing%20boat%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMarch%202%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Anti-tank%20guided%20missiles%20and%20missile%20components%20seized%20by%20HMS%20Lancaster%20from%20a%20small%20boat%20travelling%20from%20Iran%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EOctober%209%2C%202022%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ERoyal%20Navy%20frigate%20HMS%20Montrose%20recovers%20drugs%20worth%20%2417.8%20million%20from%20a%20dhow%20in%20Arabian%20Sea%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ESeptember%2027%2C%202022%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20US%20Naval%20Forces%20Central%20Command%20reports%20a%20find%20of%202.4%20tonnes%20of%20heroin%20on%20board%20fishing%20boat%20in%20Gulf%20of%20Oman%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

ABU%20DHABI%20CARD

%3Cp%3E%0D%3Cstrong%3E5pm%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Al%20Rabi%20Tower%20%E2%80%93%20Maiden%20(PA)%20Dh80%2C000%20(Turf)%201%2C400%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3E5.30pm%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Wathba%20Stallions%20Cup%20%E2%80%93%20Handicap%20(PA)%20Dh70%2C000%20(T)%201%2C600m%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3E6pm%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Abu%20Dhabi%20Championship%20%E2%80%93%20Listed%20(PA)%20Dh180%2C000%20(T)%201%2C600m%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3E6.30pm%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Hili%20Tower%20%E2%80%93%20Handicap%20(PA)%20Dh80%2C000%20(T)%202%2C200m%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3E7pm%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EUAE%20Arabian%20Derby%20%E2%80%93%20Prestige%20(PA)%20Dh150%2C000%20(T)%202%2C200m%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3E7.30pm%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Abu%20Dhabi%20Championship%20%E2%80%93%20Listed%20(TB)%20Dh380%2C000%20(T)%202%2C200m%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Classification of skills

A worker is categorised as skilled by the MOHRE based on nine levels given in the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) issued by the International Labour Organisation.

A skilled worker would be someone at a professional level (levels 1 – 5) which includes managers, professionals, technicians and associate professionals, clerical support workers, and service and sales workers.

The worker must also have an attested educational certificate higher than secondary or an equivalent certification, and earn a monthly salary of at least Dh4,000.

Indian construction workers stranded in Ajman with unpaid dues

Apple%20Mac%20through%20the%20years

%3Cp%3E1984%20-%20Apple%20unveiled%20the%20Macintosh%20on%20January%2024%3Cbr%3E1985%20-%20Steve%20Jobs%20departed%20from%20Apple%20and%20established%20NeXT%3Cbr%3E1986%20-%20Apple%20introduced%20the%20Macintosh%20Plus%2C%20featuring%20enhanced%20memory%3Cbr%3E1987%20-%20Apple%20launched%20the%20Macintosh%20II%2C%20equipped%20with%20colour%20capabilities%3Cbr%3E1989%20-%20The%20widely%20acclaimed%20Macintosh%20SE%2F30%20made%20its%20debut%3Cbr%3E1994%20-%20Apple%20presented%20the%20Power%20Macintosh%3Cbr%3E1996%20-%20The%20Macintosh%20System%20Software%20OS%20underwent%20a%20rebranding%20as%20Mac%20OS%3Cbr%3E2001%20-%20Apple%20introduced%20Mac%20OS%20X%2C%20marrying%20Unix%20stability%20with%20a%20user-friendly%20interface%3Cbr%3E2006%20-%20Apple%20adopted%20Intel%20processors%20in%20MacBook%20Pro%20laptops%3Cbr%3E2008%20-%20Apple%20introduced%20the%20MacBook%20Air%2C%20a%20lightweight%20laptop%3Cbr%3E2012%20-%20Apple%20launched%20the%20MacBook%20Pro%20with%20a%20retina%20display%3Cbr%3E2016%20-%20The%20Mac%20operating%20system%20underwent%20rebranding%20as%20macOS%3Cbr%3E2020%20-%20Apple%20introduced%20the%20M1%20chip%20for%20Macs%2C%20combining%20high%20performance%20and%20energy%20efficiency%3Cbr%3E2022%20-%20The%20M2%20chip%20was%20announced%3Cbr%3E2023%20-The%20M3%20line-up%20of%20chip%20was%20announced%20to%20improve%20performance%20and%20add%20new%20capabilities%20for%20Mac.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

MATCH INFO

Uefa Champions League, last 16, first leg

Tottenham Hotspur v Borussia Dortmund, midnight (Thursday), BeIN Sports