Robert Mugabe's mixed legacy was reflected in his funeral on Saturday, where the national stadium set aside for the event was near-empty and South Africa’s president Cyril Ramaphosa was booed as he made his address.

The contrast between his death and that of Lee Kuan Yew, the founding prime minister of Singapore, and how their nations mourned them is instructive.

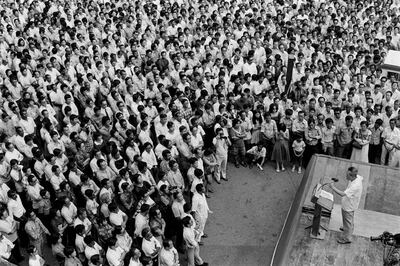

Today marks the birth date of Mr Lee, another major figure in the post-colonial developing world. When he died in 2015, he was synonymous with the city-state’s history and success.

His death was a matter of genuine national mourning in Singapore. As his country's leader from 1959 to 1990, he was widely credited with steering it From Third World to First, as the title of his second volume of memoirs put it. When he stepped down as prime minister, he remained omnipresent, first as senior minister, then minister mentor, until 2011. Was he steely-minded, even semi-authoritarian? Perhaps. But Singaporeans still recalled with affection his unapologetic insistence that he knew best, epitomised in his oft-quoted remark: "Even from my sickbed, even if you are going to lower me into the grave and I feel something is going wrong, I will get up."

At Mr Mugabe's funeral, conversely, one attendee told the Guardian newspaper: "I just came here to make sure the old man was really dead."

Earlier on, decades ago, it might have seemed as though the two had some things in common. Both were highly intelligent and well-educated. Both were anglophiles, although this was accompanied by some justified and bilious resentment on Mr Mugabe’s part.

Both were at least nominally men of the left: as well as being an African nationalist, Mr Mugabe was a Marxist-Leninist while Mr Lee’s People’s Action Party was a member of the Socialist International until 1976. But both Mr Lee and – initially – Mr Mugabe were non-ideological in their approach to government. Singapore’s finance minister Goh Keng Swee famously instructed his staff to find him a factory to open every day while Mr Mugabe eased the fears of Zimbabwe’s white minority on taking office, appointing some as ministers and impressing outsiders with his budgetary restraint, at the same time as making big investments in education and healthcare.

If Mr Mugabe had left office in 1987, he would have been remembered very differently: as a liberation hero who had done a good job, mostly – despite his government’s killing of up to 20,000 “dissenters” in Matabeleland, which the West by and large overlooked, relieved that nothing worse had happened and to protect against a backlash against white Zimbabweans.

As much as Mr Lee may have been controlling, it was always because he thought that a small island with no natural resources had to have a firm direction

But that was when he took a turn for the worse. He changed the constitution to give himself dictatorial powers, allowed the expropriation of white-owned farms by so-called war veterans and cronies and presided over a disastrous deterioration of the economy, which led to living standards being lower in 2000 than they had been in 1980 and to the country’s parlous state today.

In the end, Mr Mugabe pushed even his own supporters over the limit when he attempted to position his second wife, Grace, as his successor. The army mounted a coup and installed one of his former vice presidents, Emmerson Mnangagwa, in his place.

All of which would have been inconceivable under Mr Lee. It is true that Singapore’s current prime minister Lee Hsien Loong is his son, but a Lee dynasty has not been established. Just as well, as political dynasties in other developing countries, such as the Nehrus and Gandhis in India, have not fared well in the long term.

The younger Mr Lee’s designated successor is not from the family and there is no possible heir apparent currently in politics. As much as Mr Lee may have been controlling, it was always because he thought that a small island with no natural resources needed a firm direction. He may have enjoyed his power but power was not an end in itself: the success of the state was.

The Singaporean academic and diplomat Kishore Mahbubani puts this achievement down to three factors: meritocracy, pragmatism and honesty. Mr Lee wanted the best minds to serve government because there were no riches to fall back on. His socialism involved a great deal of government regulation of society and planning of industry but he had no qualms about accepting foreign investment. And he knew how corruption had held back so many developing countries that seemed to have much more promise of independence than Singapore.

It is no wonder that administrations around the world have sent groups to study Singapore’s example – among them the 22,000 Chinese officials who visited the island between 1990 and 2011 following the paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s exhortation to “borrow from their experiences”.

Mr Deng also praised Singapore’s social order. Western commentary is always laced with caveats about the island’s restrictions on civil liberties and political activity. That does not trouble Beijing but it should be born in mind that a state that had witnessed race riots both at home and in neighbouring Malaysia (of which Singapore was a part from 1963 to 1965) was always likely to prize stability over unfettered free speech. That is still a concern today in many countries and were Mr Lee still around, not only would he be as unapologetic as ever, he would continue to maintain the validity of the “Asian values” democratic model.

Is it perfect? Of course not. But it is telling to note where Mr Mugabe went for his medical treatment and where he died earlier this month. It was not to his capital, Harare, where electricity now runs a mere six hours a day, but Singapore, home to some of the best hospitals in the world. Would that his fellow Zimbabweans had the means to do so too. And they might, had they been blessed by a Lee Kuan Yew and not the monster that Robert Mugabe became.

Sholto Byrnes is a commentator and consultant in Kuala Lumpur and a corresponding fellow of the Erasmus Forum

If you go...

Etihad Airways flies from Abu Dhabi to Kuala Lumpur, from about Dh3,600. Air Asia currently flies from Kuala Lumpur to Terengganu, with Berjaya Hotels & Resorts planning to launch direct chartered flights to Redang Island in the near future. Rooms at The Taaras Beach and Spa Resort start from 680RM (Dh597).

Pros%20and%20cons%20of%20BNPL

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EPros%3C%2Fstrong%3E%0D%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cul%3E%0A%3Cli%3EEasy%20to%20use%20and%20require%20less%20rigorous%20credit%20checks%20than%20traditional%20credit%20options%0D%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3EOffers%20the%20ability%20to%20spread%20the%20cost%20of%20purchases%20over%20time%2C%20often%20interest-free%0D%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3EConvenient%20and%20can%20be%20integrated%20directly%20into%20the%20checkout%20process%2C%20useful%20for%20online%20shopping%0D%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3EHelps%20facilitate%20cash%20flow%20planning%20when%20used%20wisely%0D%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3C%2Ful%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECons%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cul%3E%0A%3Cli%3EThe%20ease%20of%20making%20purchases%20can%20lead%20to%20overspending%20and%20accumulation%20of%20debt%0D%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3EMissing%20payments%20can%20result%20in%20hefty%20fees%20and%2C%20in%20some%20cases%2C%20high%20interest%20rates%20after%20an%20initial%20interest-free%20period%0D%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3EFailure%20to%20make%20payments%20can%20impact%20credit%20score%20negatively%0D%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3ERefunds%20can%20be%20complicated%20and%20delayed%0D%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3C%2Ful%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cem%3ECourtesy%3A%20Carol%20Glynn%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Ruwais timeline

1971 Abu Dhabi National Oil Company established

1980 Ruwais Housing Complex built, located 10 kilometres away from industrial plants

1982 120,000 bpd capacity Ruwais refinery complex officially inaugurated by the founder of the UAE Sheikh Zayed

1984 Second phase of Ruwais Housing Complex built. Today the 7,000-unit complex houses some 24,000 people.

1985 The refinery is expanded with the commissioning of a 27,000 b/d hydro cracker complex

2009 Plans announced to build $1.2 billion fertilizer plant in Ruwais, producing urea

2010 Adnoc awards $10bn contracts for expansion of Ruwais refinery, to double capacity from 415,000 bpd

2014 Ruwais 261-outlet shopping mall opens

2014 Production starts at newly expanded Ruwais refinery, providing jet fuel and diesel and allowing the UAE to be self-sufficient for petrol supplies

2014 Etihad Rail begins transportation of sulphur from Shah and Habshan to Ruwais for export

2017 Aldar Academies to operate Adnoc’s schools including in Ruwais from September. Eight schools operate in total within the housing complex.

2018 Adnoc announces plans to invest $3.1 billion on upgrading its Ruwais refinery

2018 NMC Healthcare selected to manage operations of Ruwais Hospital

2018 Adnoc announces new downstream strategy at event in Abu Dhabi on May 13

Source: The National

The specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4-cylturbo

Transmission: seven-speed DSG automatic

Power: 242bhp

Torque: 370Nm

Price: Dh136,814

UAE tour of the Netherlands

UAE squad: Rohan Mustafa (captain), Shaiman Anwar, Ghulam Shabber, Mohammed Qasim, Rameez Shahzad, Mohammed Usman, Adnan Mufti, Chirag Suri, Ahmed Raza, Imran Haider, Mohammed Naveed, Amjad Javed, Zahoor Khan, Qadeer Ahmed

Fixtures and results:

Monday, UAE won by three wickets

Wednesday, 2nd 50-over match

Thursday, 3rd 50-over match

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

COMPANY PROFILE

Name: HyperSpace

Started: 2020

Founders: Alexander Heller, Rama Allen and Desi Gonzalez

Based: Dubai, UAE

Sector: Entertainment

Number of staff: 210

Investment raised: $75 million from investors including Galaxy Interactive, Riyadh Season, Sega Ventures and Apis Venture Partners

US%20federal%20gun%20reform%20since%20Sandy%20Hook

%3Cp%3E-%20April%2017%2C%202013%3A%20A%20bipartisan-drafted%20bill%20to%20expand%20background%20checks%20and%20ban%20assault%20weapons%20fails%20in%20the%20Senate.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20July%202015%3A%20Bill%20to%20require%20background%20checks%20for%20all%20gun%20sales%20is%20introduced%20in%20House%20of%20Representatives.%20It%20is%20not%20brought%20to%20a%20vote.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20June%2012%2C%202016%3A%20Orlando%20shooting.%20Barack%20Obama%20calls%20on%20Congress%20to%20renew%20law%20prohibiting%20sale%20of%20assault-style%20weapons%20and%20high-capacity%20magazines.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20October%201%2C%202017%3A%20Las%20Vegas%20shooting.%20US%20lawmakers%20call%20for%20banning%20bump-fire%20stocks%2C%20and%20some%20renew%20call%20for%20assault%20weapons%20ban.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20February%2014%2C%202018%3A%20Seventeen%20pupils%20are%20killed%20and%2017%20are%20wounded%20during%20a%20mass%20shooting%20in%20Parkland%2C%20Florida.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20December%2018%2C%202018%3A%20Donald%20Trump%20announces%20a%20ban%20on%20bump-fire%20stocks.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20August%202019%3A%20US%20House%20passes%20law%20expanding%20background%20checks.%20It%20is%20not%20brought%20to%20a%20vote%20in%20the%20Senate.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20April%2011%2C%202022%3A%20Joe%20Biden%20announces%20measures%20to%20crack%20down%20on%20hard-to-trace%20'ghost%20guns'.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20May%2024%2C%202022%3A%20Nineteen%20children%20and%20two%20teachers%20are%20killed%20at%20an%20elementary%20school%20in%20Uvalde%2C%20Texas.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E-%20June%2025%2C%202022%3A%20Joe%20Biden%20signs%20into%20law%20the%20first%20federal%20gun-control%20bill%20in%20decades.%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

57%20Seconds

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Rusty%20Cundieff%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EJosh%20Hutcherson%2C%20Morgan%20Freeman%2C%20Greg%20Germann%2C%20Lovie%20Simone%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2%2F5%0D%3Cbr%3E%0D%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The biog

Favourite food: Tabbouleh, greek salad and sushi

Favourite TV show: That 70s Show

Favourite animal: Ferrets, they are smart, sensitive, playful and loving

Favourite holiday destination: Seychelles, my resolution for 2020 is to visit as many spiritual retreats and animal shelters across the world as I can

Name of first pet: Eddy, a Persian cat that showed up at our home

Favourite dog breed: I love them all - if I had to pick Yorkshire terrier for small dogs and St Bernard's for big

Email sent to Uber team from chief executive Dara Khosrowshahi

From: Dara

To: Team@

Date: March 25, 2019 at 11:45pm PT

Subj: Accelerating in the Middle East

Five years ago, Uber launched in the Middle East. It was the start of an incredible journey, with millions of riders and drivers finding new ways to move and work in a dynamic region that’s become so important to Uber. Now Pakistan is one of our fastest-growing markets in the world, women are driving with Uber across Saudi Arabia, and we chose Cairo to launch our first Uber Bus product late last year.

Today we are taking the next step in this journey—well, it’s more like a leap, and a big one: in a few minutes, we’ll announce that we’ve agreed to acquire Careem. Importantly, we intend to operate Careem independently, under the leadership of co-founder and current CEO Mudassir Sheikha. I’ve gotten to know both co-founders, Mudassir and Magnus Olsson, and what they have built is truly extraordinary. They are first-class entrepreneurs who share our platform vision and, like us, have launched a wide range of products—from digital payments to food delivery—to serve consumers.

I expect many of you will ask how we arrived at this structure, meaning allowing Careem to maintain an independent brand and operate separately. After careful consideration, we decided that this framework has the advantage of letting us build new products and try new ideas across not one, but two, strong brands, with strong operators within each. Over time, by integrating parts of our networks, we can operate more efficiently, achieve even lower wait times, expand new products like high-capacity vehicles and payments, and quicken the already remarkable pace of innovation in the region.

This acquisition is subject to regulatory approval in various countries, which we don’t expect before Q1 2020. Until then, nothing changes. And since both companies will continue to largely operate separately after the acquisition, very little will change in either teams’ day-to-day operations post-close. Today’s news is a testament to the incredible business our team has worked so hard to build.

It’s a great day for the Middle East, for the region’s thriving tech sector, for Careem, and for Uber.

Uber on,

Dara

COMPANY%20PROFILE%20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECompany%20name%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENomad%20Homes%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarted%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2020%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EHelen%20Chen%2C%20Damien%20Drap%2C%20and%20Dan%20Piehler%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20UAE%20and%20Europe%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EIndustry%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3A%20PropTech%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFunds%20raised%20so%20far%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20%2444m%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Acrew%20Capital%2C%2001%20Advisors%2C%20HighSage%20Ventures%2C%20Abstract%20Ventures%2C%20Partech%2C%20Precursor%20Ventures%2C%20Potluck%20Ventures%2C%20Knollwood%20and%20several%20undisclosed%20hedge%20funds%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

How Filipinos in the UAE invest

A recent survey of 10,000 Filipino expatriates in the UAE found that 82 per cent have plans to invest, primarily in property. This is significantly higher than the 2014 poll showing only two out of 10 Filipinos planned to invest.

Fifty-five percent said they plan to invest in property, according to the poll conducted by the New Perspective Media Group, organiser of the Philippine Property and Investment Exhibition. Acquiring a franchised business or starting up a small business was preferred by 25 per cent and 15 per cent said they will invest in mutual funds. The rest said they are keen to invest in insurance (3 per cent) and gold (2 per cent).

Of the 5,500 respondents who preferred property as their primary investment, 54 per cent said they plan to make the purchase within the next year. Manila was the top location, preferred by 53 per cent.

Indoor cricket in a nutshell

Indoor cricket in a nutshell

Indoor Cricket World Cup - Sept 16-20, Insportz, Dubai

16 Indoor cricket matches are 16 overs per side

8 There are eight players per team

9 There have been nine Indoor Cricket World Cups for men. Australia have won every one.

5 Five runs are deducted from the score when a wickets falls

4 Batsmen bat in pairs, facing four overs per partnership

Scoring In indoor cricket, runs are scored by way of both physical and bonus runs. Physical runs are scored by both batsmen completing a run from one crease to the other. Bonus runs are scored when the ball hits a net in different zones, but only when at least one physical run is score.

Zones

A Front net, behind the striker and wicketkeeper: 0 runs

B Side nets, between the striker and halfway down the pitch: 1 run

C Side nets between halfway and the bowlers end: 2 runs

D Back net: 4 runs on the bounce, 6 runs on the full

Getting%20there%20and%20where%20to%20stay

%3Cp%3EFly%20with%20Etihad%20Airways%20from%20Abu%20Dhabi%20to%20New%20York%E2%80%99s%20JFK.%20There's%2011%20flights%20a%20week%20and%20economy%20fares%20start%20at%20around%20Dh5%2C000.%3Cbr%3EStay%20at%20The%20Mark%20Hotel%20on%20the%20city%E2%80%99s%20Upper%20East%20Side.%20Overnight%20stays%20start%20from%20%241395%20per%20night.%3Cbr%3EVisit%20NYC%20Go%2C%20the%20official%20destination%20resource%20for%20New%20York%20City%20for%20all%20the%20latest%20events%2C%20activites%20and%20openings.%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A