If satire is dead, someone didn’t tell the script writers. That the real thing is too outrageous to be sent up is sometimes true, but the idea that there is no role for savage comedy is about to be tested to destruction.

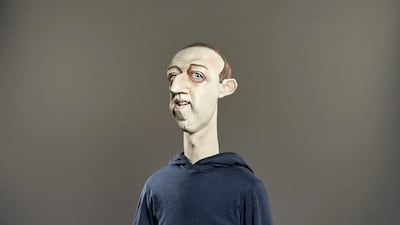

Spitting Image, the world-renowned latex puppet show that started in the 1980s, is being re-launched in the UK.

The show seeks to hone in on the rise of personality-driven politicians, as a contrast to the last generation of blander fare. The challenge is that it must surmount the basic test of putting an original spin on the madness of the moment. So long as it can exploit the personalities as raw material, the role of master satirists beckons.

The show was cancelled in 1996 as a new type of centrist politics took hold across the West. Its founder Roger Law took to living in Sydney and flying to China to nurture an obsession with Chinese ceramics.

Having met him occasionally during that period, I would vouch that Mr Law has the strength of mind equal to the moment of making comedy out of the current crop.

The photos released of the latest generation of puppets look like great caricatures. In a recent interview, Mr Law was asked about the irony of him as a 79-year-old mocking the septuagenarian contenders for the White House. It is not much fun being old, he said, given that it takes about two hours to get going in the morning. The obvious jokes are out.

In the roughly 25 years between the two Spitting Image shows, there have been many commentators who examined the demise of the satirists' trade.

At its best, satire provides an outlet for the weak to share in a light-hearted stand against the powerful. But when moderates rule politics, there is no overpowering apex that imposes its will on the population. Politicians, instead, rely on so-called "nudge" techniques, which include positing ideas for the public and then developing campaigns around their compliance or uptake. The problem for satirists is that these techniques are antithetical to their art.

Political comedians have resorted to challenging these processes. But while television shows such as Veep, The Thick of It and Twenty Twelve were funny, they dealt primarily in riffs about language and small feud scenes among political staffers.

There has, however, been a cultural shift in recent years.

The British general election in 2015 was won on a slogan that, in hindsight, was ultra-ironic.

The vote was a choice between the Conservatives and five years of chaos with a fairly bumbling opposition leader called Ed Miliband. Mr Miliband did not help himself by carving his mostly unintelligible campaign pledges on a massive stone slab. The launch of the “EdStone” was a scene that the late film director Stanley Kubrick would have gleefully choreographed. But as it turns out, the Labour leader was beaten.

And yet, the subsequent five years of Conservative rule have been plenty filled with chaos. The smooth-faced David Cameron was the victor in 2015. But even though he gleefully painted himself as the heir to former prime minister Tony Blair, he was forcefully retired by a referendum electorate just a year later, leading to a process that eventually saw flaxen-haired Boris Johnson rise to power.

In that same year, then US president Barack Obama made a fateful error of riding roughshod over his vice president Joe Biden’s presidential ambitions. Mr Obama wanted to throw his weight behind Hillary Clinton, who went up against Donald Trump, but her bid was shredded in the 2016 election.

Mrs Clinton’s achievements are many but she belonged to the satire-free zone, as did Mr Obama.

Mr Trump and Mr Johnson, on the other hand, are rich and ripe political characters. So, too, is Mr Biden, who is a living embodiment of the Warner Brothers' cartoon character Foghorn Leghorn.

For clues on how the new Spitting Image producers and writers plan to pitch their skits, it is perhaps useful to look at the work of the writer Michael Spicer.

In the Room Next Door social media series, he poses as a political aide providing earpiece guidance to leaders during speeches or interviews. The basic premise is Spicer guiding or shaping the message; in other words, he is not coming up with the message but channelling how it is coming across.

As a comedy technique, it rests on inverting the established rules. Even in the set-up, the politicians are, metaphorically speaking, hanging themselves by not following the script writers.

Spicer seized on the British interior minister Priti Patel repeatedly referring to "victims of counterterrorism" as she muddled her department's role in fighting terrorism and overseeing counter-extremism policy. In doing so, Spicer showed that there was still life in approaches that had been neglected since the heyday of Spitting Image, when it was dealing with former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and former US president Ronald Reagan.

In the political mosh pit of the centre, political personalities are lost to sight of all but insiders and close observers. For the current heavyweights, the name of the game is to create their own political landscape. An outsized personality is key to forging these new realities. And it takes humourists, perhaps even rubberised puppets, to be an essential guide to true characters that are leading the way.

Damien McElroy is the London bureau chief of The National