Today, Hollywood actor William Shatner will become the oldest man ever to go into space. He is not an astronaut, will operate no controls and has only done a few days’ training with other crew members, who, like him, are civilians. His trip is a sign of the remarkable pace at which space tourism is lifting off, fuelled by a private space race that in July was won by British billionaire Richard Branson, whose company Virgin Galactic flew him nearly 86 kilometres above the earth's surface, technically outer space.

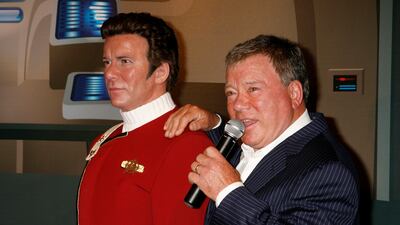

But the symbolism of Shatner’s trip runs deeper than showing the pace at which this new frontier in tourism is developing. Shatner’s career is defined by his role in Star Trek as commander of the USS Enterprise, Captain Kirk. The franchise of films and series has been running since the late 1960s.

More than just futuristic sets and odd outfits, Star Trek investigated remarkable, eccentric characters, whose human ambition and bravery - even among its alien characters - introduced viewers to an exploratory, brave spirit captured in the show’s mantra “to boldly go”.

Shatner’s character was arguably the bravest of the lot. But today, closer to earth, the actor admits to being a lot more nervous than Captain Kirk would have been. This is completely understandable. He will be sent as much as 100 kilometres above earth’s surface and experience weightlessness in a trip of just 10 minutes.

Those figures would seem impossibly scary to many. Nonetheless, there is increasing and stubborn consumer confidence in the sector, even in spite of early footage of companies trying to develop reusable rockets – crucial to making trips profitable – going spectacularly wrong. Thus far, however, all flights involving humans have gone as planned.

And the wider industry clearly has confidence that much more can be done. There are even plans to open a space hotel as early as 2027. Officials for the International Space Station, on the other hand, have warned recently that potentially “irreparable” damage is appearing in the platform. Could the contrast with commercial space exploration’s glitzy ascent in the past few years be an indication that state-backed ventures of the 20th century have to give some way to the private sector?

There is also serious money to be made. Virgin Galactic has more than 600 future astronauts on its waiting list. The rival billionaire who is bankrolling Shatner’s trip, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, has sold another ticket to a private buyer for $28 million. The company Space Perspective claims to have already got 475 reservations for trips aboard their balloon-elevated craft that will take passengers more than 30km high in two hours at $125,000 a seat. They plan to start trips in 2024.

But today, all eyes are on Shatner, who can ditch a world of alien ears, cyborg friends and vast space cities; there is increasingly little fiction in the story of the universe. What finally got him out of this world was not CGI and a set designer, but his status, career success, the competitiveness of the world’s richest people and the enduring human desire to explore, whether at home or in the stars.