When it comes to fads, human culture is endlessly inventive. Over the past 100 years, people have gone wild for hula hoops, 3D glasses, a whole collection of different dance crazes as well as Rubik’s cubes and Tamagotchis. The internet era has added a new category of collective – if short-lived – enthusiasms from Rickrolling, Facebook personality quizzes and email chain letters to the ice-bucket challenge and the Harlem Shake.

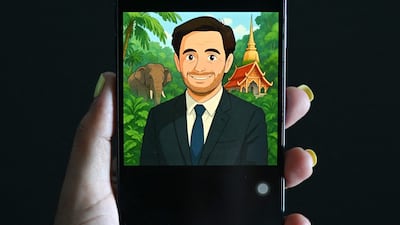

The recent release by Open AI of an advanced ChatGPT image generator that can recreate photos in the style of Japan’s famous Ghibli animation studio has arguably created the 21st century’s latest craze. OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman has claimed that ChatGPT gained a million new users in an hour, posting on X that the company’s “GPUs are melting” as people across the world clamour for this new form of AI-generated art.

The meme is everywhere on social media. Most of the images generated are light-hearted – family photos, recreations of famous historical images and some corporate advertisements. Others are controversial or even sinister – the Israeli military, for instance, has created Ghibli-style images of its soldiers as they continue their bombing campaign in Gaza.

The rendering of personal photographs into whimsical Japanese cartoons may prove to be another flash in the pan. Nevertheless, it reveals the power of big tech and underlines the breath-taking speed at which online innovations can break out of the computer lab and into our everyday lives. This calls for hard thinking about the ethical and responsible uses of these powerful – and growing – technologies.

The excitement about the Ghibli tool is understandable. It is fun, culturally relatable and an accessible way for people to enjoy powerfully creative technology. But such excitement should be tempered by caution. That many people are reflexively uploading photos of themselves and their loved ones, in addition to their personal details, should raise concerns about how their data and likenesses are being put to use.

There are also concerns about copyright, intellectual property and the wider ethics of using human-generated work to produce digital images. Hayao Miyazaki, the co-founder of Studio Ghibli world, is on record as saying that AI-generated animation is an "insult to life itself". Others share this queasiness about mixing AI with human creativity – in February, thousands of people signed an open letter addressed to Christie’s auction house in New York, urging it to cancel a planned sale of AI-derived art, claiming that it used “AI models that are known to be trained on copyrighted work without a license”. “These models and the companies behind them,” the letter added, “exploit human artists, using their work without permission or payment to build commercial AI products that compete with them.”

The answer to the challenging questions posed by such innovations lies somewhere between wholehearted adoption and knee-jerk rejection

As is often the case, the answer to the challenging questions posed by such innovations lies somewhere between wholehearted adoption and knee-jerk rejection. In the UAE – an early adopter of digital technologies such as AI – a measured approach has been evident for years. Last week, this was summed up by Omran Sharaf, assistant foreign minister for advanced science and technology, who told an AI summit in Geneva that: "We shouldn’t be paranoid, we should be very smart about the way we approach it … But, at the same time, we should be very cautious not to be reckless about it, and work on systems that ensure responsible behaviour, bring transparency and make sure there are controls put in place so that it doesn’t fall into the wrong hands."

It is this open-minded but qualified embrace of advanced technology that provides the best way forward. Informed caution can act as a steadying counterweight to the pull of the latest online fad.

if you go

The flights Fly Dubai, Air Arabia, Emirates, Etihad, and Royal Jordanian all offer direct, three-and-a-half-hour flights from the UAE to the Jordanian capital Amman. Alternatively, from June Fly Dubai will offer a new direct service from Dubai to Aqaba in the south of the country. See the airlines’ respective sites for varying prices or search on reliable price-comparison site Skyscanner.

The trip

Jamie Lafferty was a guest of the Jordan Tourist Board. For more information on adventure tourism in Jordan see Visit Jordan. A number of new and established tour companies offer the chance to go caving, rock-climbing, canyoning, and mountaineering in Jordan. Prices vary depending on how many activities you want to do and how many days you plan to stay in the country. Among the leaders are Terhaal, who offer a two-day canyoning trip from Dh845 per person. If you really want to push your limits, contact the Stronger Team. For a more trek-focused trip, KE Adventure offers an eight-day trip from Dh5,300 per person.

Why it pays to compare

A comparison of sending Dh20,000 from the UAE using two different routes at the same time - the first direct from a UAE bank to a bank in Germany, and the second from the same UAE bank via an online platform to Germany - found key differences in cost and speed. The transfers were both initiated on January 30.

Route 1: bank transfer

The UAE bank charged Dh152.25 for the Dh20,000 transfer. On top of that, their exchange rate margin added a difference of around Dh415, compared with the mid-market rate.

Total cost: Dh567.25 - around 2.9 per cent of the total amount

Total received: €4,670.30

Route 2: online platform

The UAE bank’s charge for sending Dh20,000 to a UK dirham-denominated account was Dh2.10. The exchange rate margin cost was Dh60, plus a Dh12 fee.

Total cost: Dh74.10, around 0.4 per cent of the transaction

Total received: €4,756

The UAE bank transfer was far quicker – around two to three working days, while the online platform took around four to five days, but was considerably cheaper. In the online platform transfer, the funds were also exposed to currency risk during the period it took for them to arrive.

Players Selected for La Liga Trials

U18 Age Group

Name: Ahmed Salam (Malaga)

Position: Right Wing

Nationality: Jordanian

Name: Yahia Iraqi (Malaga)

Position: Left Wing

Nationality: Morocco

Name: Mohammed Bouherrafa (Almeria)

Position: Centre-Midfield

Nationality: French

Name: Mohammed Rajeh (Cadiz)

Position: Striker

Nationality: Jordanian

U16 Age Group

Name: Mehdi Elkhamlichi (Malaga)

Position: Lead Striker

Nationality: Morocco

Superliminal%20

%3Cp%3EDeveloper%3A%20Pillow%20Castle%20Games%0D%3Cbr%3EPublisher%3A%20Pillow%20Castle%20Games%0D%3Cbr%3EConsole%3A%20PlayStation%204%26amp%3B5%2C%20Xbox%20Series%20One%20%26amp%3B%20X%2FS%2C%20Nintendo%20Switch%2C%20PC%20and%20Mac%0D%3Cbr%3ERating%3A%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The specs

Engine: Four electric motors, one at each wheel

Power: 579hp

Torque: 859Nm

Transmission: Single-speed automatic

Price: From Dh825,900

On sale: Now

ACL Elite (West) - fixtures

Monday, Sept 30

Al Sadd v Esteghlal (8pm)

Persepolis v Pakhtakor (8pm)

Al Wasl v Al Ahli (8pm)

Al Nassr v Al Rayyan (10pm)

Tuesday, Oct 1

Al Hilal v Al Shorta (10pm)

Al Gharafa v Al Ain (10pm)

Farasan Boat: 128km Away from Anchorage

Director: Mowaffaq Alobaid

Stars: Abdulaziz Almadhi, Mohammed Al Akkasi, Ali Al Suhaibani

Rating: 4/5

THE 12 BREAKAWAY CLUBS

England

Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United, Tottenham Hotspur

Italy

AC Milan, Inter Milan, Juventus

Spain

Atletico Madrid, Barcelona, Real Madrid

Brief scoreline:

Manchester United 0

Manchester City 2

Bernardo Silva 54', Sane 66'

TCL INFO

Teams:

Punjabi Legends Owners: Inzamam-ul-Haq and Intizar-ul-Haq; Key player: Misbah-ul-Haq

Pakhtoons Owners: Habib Khan and Tajuddin Khan; Key player: Shahid Afridi

Maratha Arabians Owners: Sohail Khan, Ali Tumbi, Parvez Khan; Key player: Virender Sehwag

Bangla Tigers Owners: Shirajuddin Alam, Yasin Choudhary, Neelesh Bhatnager, Anis and Rizwan Sajan; Key player: TBC

Colombo Lions Owners: Sri Lanka Cricket; Key player: TBC

Kerala Kings Owners: Hussain Adam Ali and Shafi Ul Mulk; Key player: Eoin Morgan

Venue Sharjah Cricket Stadium

Format 10 overs per side, matches last for 90 minutes

When December 14-17

Dr Afridi's warning signs of digital addiction

Spending an excessive amount of time on the phone.

Neglecting personal, social, or academic responsibilities.

Losing interest in other activities or hobbies that were once enjoyed.

Having withdrawal symptoms like feeling anxious, restless, or upset when the technology is not available.

Experiencing sleep disturbances or changes in sleep patterns.

What are the guidelines?

Under 18 months: Avoid screen time altogether, except for video chatting with family.

Aged 18-24 months: If screens are introduced, it should be high-quality content watched with a caregiver to help the child understand what they are seeing.

Aged 2-5 years: Limit to one-hour per day of high-quality programming, with co-viewing whenever possible.

Aged 6-12 years: Set consistent limits on screen time to ensure it does not interfere with sleep, physical activity, or social interactions.

Teenagers: Encourage a balanced approach – screens should not replace sleep, exercise, or face-to-face socialisation.

Source: American Paediatric Association

The specs

Engine: 3.0-litre six-cylinder MHEV

Power: 360bhp

Torque: 500Nm

Transmission: eight-speed automatic

Price: from Dh282,870

On sale: now