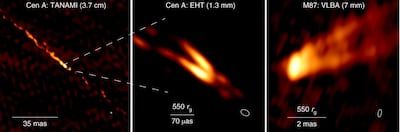

A mysterious jet of energy has been captured emerging from a supermassive black hole, in a detailed photograph by the telescope that took the first picture of a black hole two years ago.

The Event Horizon Telescope, consisting of eight radio observatories that act as one Earth-sized telescope, caught the enormous jet escaping from a black hole in the centre of the Centaurus A galaxy. The findings were published in the Nature Astronomy journal on Monday.

This allows us for the first time to see and study an extragalactic radio jet on scales smaller than the distance light travels in one day

Michael Janssen,

astronomer

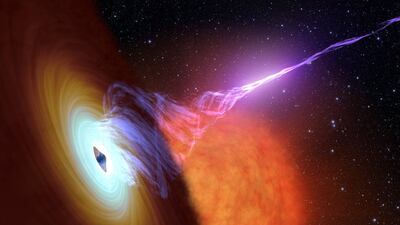

Supermassive black holes – which are the largest type and are millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun – destroy most nearby matter, including gas and dust, through their gravitational pull.

But some surrounding particles escape moments before capture and are blown out into space, creating jets.

For decades, astronomers have been trying to study how the phenomenon occurs.

"This allows us for the first time to see and study an extragalactic radio jet on scales smaller than the distance light travels in one day,” said Michael Janssen, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn and Radboud University Nijmegen.

“We see up close and personal how a monstrously gigantic jet launched by a supermassive black hole is being born.”

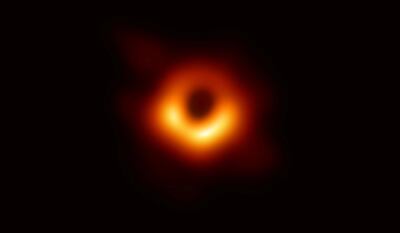

In April 2019, the first image of a black hole was released, after the telescope captured M87 – a supermassive black hole with a mass more than six million times that of the Sun.

The latest observations were made at 10 times the frequency of any previous recordings, at a resolution that was 16 times sharper, allowing astronomers to study the black hole and the jet in detail.

“It’s amazing that we can study Centaurus A now with the extreme resolution of the EHT. We have never seen this nucleus before, as we didn't have sufficiently high resolution and we weren't looking at high enough frequencies,” said Maciek Wielgus, co-author of the study and researcher at Harvard and Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics.

"Centaurus A is our close neighbour in the intergalactic sense – it’s only about 10 million light years away. And its central region is very different from our own galactic centre – there’s so much more power emerging from the nucleus of Centaurus A.”

Through the findings, astronomers are trying to understand how jets are launched from these central regions and how they are able to extend over scales that are larger than their host galaxies without dispersing.

The new images show the jet is brighter at the edges than at the centre.

"Theoretically, jets can collide with galactic gas and heat up the edge, but the details of such a process so close to the black hole are a complete mystery,” Koushik Chatterjee, a study co-author and researcher at the Centre for Astrophysics and the Black Hole Initiative, said.

“The brightness contrast between the centre and the edge could potentially provide us with new insights about the plasma physics both within and around jets, making Centaurus A an exciting target for next-generation black hole simulations.”

Researchers now hope to photograph the central black hole of Centaurus A at even higher resolutions.

The wonders of space - in pictures

Where to donate in the UAE

The Emirates Charity Portal

You can donate to several registered charities through a “donation catalogue”. The use of the donation is quite specific, such as buying a fan for a poor family in Niger for Dh130.

The General Authority of Islamic Affairs & Endowments

The site has an e-donation service accepting debit card, credit card or e-Dirham, an electronic payment tool developed by the Ministry of Finance and First Abu Dhabi Bank.

Al Noor Special Needs Centre

You can donate online or order Smiles n’ Stuff products handcrafted by Al Noor students. The centre publishes a wish list of extras needed, starting at Dh500.

Beit Al Khair Society

Beit Al Khair Society has the motto “From – and to – the UAE,” with donations going towards the neediest in the country. Its website has a list of physical donation sites, but people can also contribute money by SMS, bank transfer and through the hotline 800-22554.

Dar Al Ber Society

Dar Al Ber Society, which has charity projects in 39 countries, accept cash payments, money transfers or SMS donations. Its donation hotline is 800-79.

Dubai Cares

Dubai Cares provides several options for individuals and companies to donate, including online, through banks, at retail outlets, via phone and by purchasing Dubai Cares branded merchandise. It is currently running a campaign called Bookings 2030, which allows people to help change the future of six underprivileged children and young people.

Emirates Airline Foundation

Those who travel on Emirates have undoubtedly seen the little donation envelopes in the seat pockets. But the foundation also accepts donations online and in the form of Skywards Miles. Donated miles are used to sponsor travel for doctors, surgeons, engineers and other professionals volunteering on humanitarian missions around the world.

Emirates Red Crescent

On the Emirates Red Crescent website you can choose between 35 different purposes for your donation, such as providing food for fasters, supporting debtors and contributing to a refugee women fund. It also has a list of bank accounts for each donation type.

Gulf for Good

Gulf for Good raises funds for partner charity projects through challenges, like climbing Kilimanjaro and cycling through Thailand. This year’s projects are in partnership with Street Child Nepal, Larchfield Kids, the Foundation for African Empowerment and SOS Children's Villages. Since 2001, the organisation has raised more than $3.5 million (Dh12.8m) in support of over 50 children’s charities.

Noor Dubai Foundation

Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum launched the Noor Dubai Foundation a decade ago with the aim of eliminating all forms of preventable blindness globally. You can donate Dh50 to support mobile eye camps by texting the word “Noor” to 4565 (Etisalat) or 4849 (du).

What is a robo-adviser?

Robo-advisers use an online sign-up process to gauge an investor’s risk tolerance by feeding information such as their age, income, saving goals and investment history into an algorithm, which then assigns them an investment portfolio, ranging from more conservative to higher risk ones.

These portfolios are made up of exchange traded funds (ETFs) with exposure to indices such as US and global equities, fixed-income products like bonds, though exposure to real estate, commodity ETFs or gold is also possible.

Investing in ETFs allows robo-advisers to offer fees far lower than traditional investments, such as actively managed mutual funds bought through a bank or broker. Investors can buy ETFs directly via a brokerage, but with robo-advisers they benefit from investment portfolios matched to their risk tolerance as well as being user friendly.

Many robo-advisers charge what are called wrap fees, meaning there are no additional fees such as subscription or withdrawal fees, success fees or fees for rebalancing.

Dubai Rugby Sevens

November 30-December 2, at The Sevens, Dubai

Gulf Under 19

Pool A – Abu Dhabi Harlequins, Jumeirah College Tigers, Dubai English Speaking School 1, Gems World Academy

Pool B – British School Al Khubairat, Bahrain Colts, Jumeirah College Lions, Dubai English Speaking School 2

Pool C - Dubai College A, Dubai Sharks, Jumeirah English Speaking School, Al Yasmina

Pool D – Dubai Exiles, Dubai Hurricanes, Al Ain Amblers, Deira International School

Fatherland

Kele Okereke

(BMG)

UAE%20ILT20

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EMarquee%20players%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%0D%3Cbr%3EMoeen%20Ali%2C%20Andre%20Russell%2C%20Dawid%20Malan%2C%20Wanindu%20Hasiranga%2C%20Sunil%20Narine%2C%20Evin%20Lewis%2C%20Colin%20Munro%2C%20Fabien%20Allen%2C%20Sam%20Billings%2C%20Tom%20Curran%2C%20Alex%20Hales%2C%20Dushmantha%20Chameera%2C%20Shimron%20Hetmyer%2C%20Akeal%20Hosein%2C%20Chris%20Jordan%2C%20Tom%20Banton%2C%20Sandeep%20Lamichhane%2C%20Chris%20Lynn%2C%20Rovman%20Powell%2C%20Bhanuka%20Rajapaksa%2C%20Mujeeb%20Ul%20Rahman%0D%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInternational%20players%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%0D%3Cbr%3ELahiru%20Kumara%2C%20Seekugge%20Prassanna%2C%20Charith%20Asalanka%2C%20Colin%20Ingram%2C%20Paul%20Stirling%2C%20Kennar%20Lewis%2C%20Ali%20Khan%2C%20Brandon%20Glover%2C%20Ravi%20Rampaul%2C%20Raymon%20Reifer%2C%20Isuru%20Udana%2C%20Blessing%20Muzarabani%2C%20Niroshan%20Dickwella%2C%20Hazaratullah%20Zazai%2C%20Frederick%20Klassen%2C%20Sikandar%20Raja%2C%20George%20Munsey%2C%20Dan%20Lawrence%2C%20Dominic%20Drakes%2C%20Jamie%20Overton%2C%20Liam%20Dawson%2C%20David%20Wiese%2C%20Qais%20Ahmed%2C%20Richard%20Gleeson%2C%20James%20Vince%2C%20Noor%20Ahmed%2C%20Rahmanullah%20Gurbaz%2C%20Navin%20Ul%20Haq%2C%20Sherfane%20Rutherford%2C%20Saqib%20Mahmood%2C%20Ben%20Duckett%2C%20Benny%20Howell%2C%20Ruben%20Trumpelman%0D%3Cbr%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

LIKELY TEAMS

South Africa

Faf du Plessis (captain), Dean Elgar, Aiden Markram, Hashim Amla, AB de Villiers, Quinton de Kock (wkt), Vernon Philander, Keshav Maharaj, Kagiso Rabada, Morne Morkel, Lungi Ngidi.

India (from)

Virat Kohli (captain), Murali Vijay, Lokesh Rahul, Cheteshwar Pujara, Rohit Sharma, Ajinkya Rahane, Hardik Pandya, Dinesh Karthik (wkt), Ravichandran Ashwin, Bhuvneshwar Kumar, Ishant Sharma, Mohammad Shami, Jasprit Bumrah.

%20Ramez%20Gab%20Min%20El%20Akher

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ECreator%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Ramez%20Galal%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarring%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Ramez%20Galal%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStreaming%20on%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EMBC%20Shahid%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E2.5%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The specs: 2018 Peugeot 5008

Price, base / as tested: Dh99,900 / Dh134,900

Engine: 1.6-litre turbocharged four-cylinder

Transmission: Six-speed automatic

Power: 165hp @ 6,000rpm

Torque: 240Nm @ 1,400rpm

Fuel economy, combined: 5.8L / 100km

Getting%20there%20

%3Cp%3E%3Ca%20href%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fwww.thenationalnews.com%2Ftravel%2F2023%2F01%2F12%2Fwhat-does-it-take-to-be-cabin-crew-at-one-of-the-worlds-best-airlines-in-2023%2F%22%20target%3D%22_self%22%3EEtihad%20Airways%20%3C%2Fa%3Eflies%20daily%20to%20the%20Maldives%20from%20Abu%20Dhabi.%20The%20journey%20takes%20four%20hours%20and%20return%20fares%20start%20from%20Dh3%2C995.%20Opt%20for%20the%203am%20flight%20and%20you%E2%80%99ll%20land%20at%206am%2C%20giving%20you%20the%20entire%20day%20to%20adjust%20to%20island%20time.%20%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ERound%20trip%20speedboat%20transfers%20to%20the%20resort%20are%20bookable%20via%20Anantara%20and%20cost%20%24265%20per%20person.%20%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Living in...

This article is part of a guide on where to live in the UAE. Our reporters will profile some of the country’s most desirable districts, provide an estimate of rental prices and introduce you to some of the residents who call each area home.

GAC GS8 Specs

Engine: 2.0-litre 4cyl turbo

Power: 248hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 400Nm at 1,750-4,000rpm

Transmission: 8-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 9.1L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh149,900

Afro%20salons

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EFor%20women%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3Cbr%3ESisu%20Hair%20Salon%2C%20Jumeirah%201%2C%20Dubai%3Cbr%3EBoho%20Salon%2C%20Al%20Barsha%20South%2C%20Dubai%3Cbr%3EMoonlight%2C%20Al%20Falah%20Street%2C%20Abu%20Dhabi%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFor%20men%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3Cbr%3EMK%20Barbershop%2C%20Dar%20Al%20Wasl%20Mall%2C%20Dubai%3Cbr%3ERegency%20Saloon%2C%20Al%20Zahiyah%2C%20Abu%20Dhabi%3Cbr%3EUptown%20Barbershop%2C%20Al%20Nasseriya%2C%20Sharjah%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The Brutalist

Director: Brady Corbet

Stars: Adrien Brody, Felicity Jones, Guy Pearce, Joe Alwyn

Rating: 3.5/5

Brief scores:

Everton 0

Leicester City 1

Vardy 58'

Mercer, the investment consulting arm of US services company Marsh & McLennan, expects its wealth division to at least double its assets under management (AUM) in the Middle East as wealth in the region continues to grow despite economic headwinds, a company official said.

Mercer Wealth, which globally has $160 billion in AUM, plans to boost its AUM in the region to $2-$3bn in the next 2-3 years from the present $1bn, said Yasir AbuShaban, a Dubai-based principal with Mercer Wealth.

“Within the next two to three years, we are looking at reaching $2 to $3 billion as a conservative estimate and we do see an opportunity to do so,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Mercer does not directly make investments, but allocates clients’ money they have discretion to, to professional asset managers. They also provide advice to clients.

“We have buying power. We can negotiate on their (client’s) behalf with asset managers to provide them lower fees than they otherwise would have to get on their own,” he added.

Mercer Wealth’s clients include sovereign wealth funds, family offices, and insurance companies among others.

From its office in Dubai, Mercer also looks after Africa, India and Turkey, where they also see opportunity for growth.

Wealth creation in Middle East and Africa (MEA) grew 8.5 per cent to $8.1 trillion last year from $7.5tn in 2015, higher than last year’s global average of 6 per cent and the second-highest growth in a region after Asia-Pacific which grew 9.9 per cent, according to consultancy Boston Consulting Group (BCG). In the region, where wealth grew just 1.9 per cent in 2015 compared with 2014, a pickup in oil prices has helped in wealth generation.

BCG is forecasting MEA wealth will rise to $12tn by 2021, growing at an annual average of 8 per cent.

Drivers of wealth generation in the region will be split evenly between new wealth creation and growth of performance of existing assets, according to BCG.

Another general trend in the region is clients’ looking for a comprehensive approach to investing, according to Mr AbuShaban.

“Institutional investors or some of the families are seeing a slowdown in the available capital they have to invest and in that sense they are looking at optimizing the way they manage their portfolios and making sure they are not investing haphazardly and different parts of their investment are working together,” said Mr AbuShaban.

Some clients also have a higher appetite for risk, given the low interest-rate environment that does not provide enough yield for some institutional investors. These clients are keen to invest in illiquid assets, such as private equity and infrastructure.

“What we have seen is a desire for higher returns in what has been a low-return environment specifically in various fixed income or bonds,” he said.

“In this environment, we have seen a de facto increase in the risk that clients are taking in things like illiquid investments, private equity investments, infrastructure and private debt, those kind of investments were higher illiquidity results in incrementally higher returns.”

The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, one of the largest sovereign wealth funds, said in its 2016 report that has gradually increased its exposure in direct private equity and private credit transactions, mainly in Asian markets and especially in China and India. The authority’s private equity department focused on structured equities owing to “their defensive characteristics.”

The Details

Article 15

Produced by: Carnival Cinemas, Zee Studios

Directed by: Anubhav Sinha

Starring: Ayushmann Khurrana, Kumud Mishra, Manoj Pahwa, Sayani Gupta, Zeeshan Ayyub

Our rating: 4/5

The specs

Engine: 6.2-litre V8

Transmission: ten-speed

Power: 420bhp

Torque: 624Nm

Price: Dh325,125

On sale: Now