It’s a riddle of cosmic proportions: how can the universe contain stars older than itself?

That’s the conundrum now facing astronomers trying to establish the age of the universe – and its resolution could spark a scientific revolution.

At an international conference held in California last month, there was hope a resolution might be found. Instead, the latest findings only confirmed suspicions there is something fundamentally wrong with current ideas of how the universe works.

Those theories are based on Einstein’s theory of gravity, known as General Relativity, which he developed more than a century ago.

It’s arguably the most successful scientific theory devised – its predictions about everything from black holes to the effect of gravity on time have been confirmed with exquisite accuracy.

But applying GR to the whole universe has often led to surprising results.

The first was discovered by Einstein himself, who found his theory implied the universe must be expanding. This defied common sense – not least because it hinted that the universe must have had a beginning – and led Einstein to tweak his equations to bring them into line with reality.

Yet by the late 1920s, astronomers had found the original equations were right: the universe is expanding. This led them to estimate when the expansion began – and thus the age of the universe.

Then came the next shock: the figure that emerged was barely two billion years, implying the universe was less than half as old as Earth.

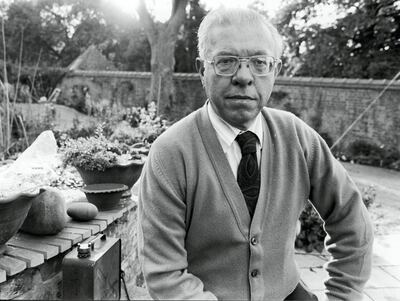

Faced with this paradox, the British astrophysicist Prof Fred Hoyle of the University of Cambridge came up with the idea of a mysterious new force of nature that somehow emerged from empty space.

When combined with Einstein’s equations, this had the effect of making the universe infinitely old – thus solving the age problem.

At the time, Prof Fred’s idea seemed even more mysterious than the puzzle it was supposed to solve. Most scientists were happy to ditch it when new observations suggested the universe was about 10 to 20 billion years old – comfortably more than the age of our planet.

But now, theorists are looking again at such “crazy” ideas, because the age problem is back with a vengeance.

At last month’s meeting, several teams of astronomers gave their latest estimates for the date of the Big Bang, in which the universe was created.

Until recently, such findings would have barely caused a stir, as the age of the cosmos was thought to have been revealed a decade ago by studies of the heat left over by the Big Bang.

By measuring the spread of that heat across the night sky, orbiting satellites had shown the primordial explosion must have taken place about 13.8 billion years ago, plus or minus a few tens of millions of years.

As well as being impressively precise, this value tied in well with those found by direct measurements of the cosmic expansion using stars in distant galaxies. It also made the universe older than the most ancient stars then known.

But now the universe has thrown astronomers another curve ball. The latest studies suggest the universe has two different ages.

Measurements made using relatively nearby galaxies suggest the universe is hundreds of millions of years younger than the age indicated by the heat still radiating outwards from the Big Bang. And the difference between them seems too large to dismiss as a fluke.

Worse still, some of the results now imply that the universe is younger than the oldest known star.

Code-named HD 140283, the so-called Methuselah star was first catalogued in 1912, and lies only 190 light years from Earth.

It seems pretty unremarkable, but astronomers now know it contains very little iron – which means it must have been formed before this element became common in the universe. And that implies HD 140283 must be almost as old as the universe itself.

In 2013, astronomers using the orbiting Hubble Space Telescope estimated Methuselah was about 14.5 billion years old, give or take about 800 million years. That’s hard to square with the latest estimates of the age of the universe.

So what’s going on? One obvious explanation is that history is merely repeating itself, and something is wrong with the new estimates of the age of the universe.

Most of these are based on the rate of expansion of the universe, which in turn needs accurate values for both the speed galaxies are moving away from one another, and their distances.

The most likely source of error is the latter: astronomers have to make many assumptions to estimate the distances to far-away galaxies, and these have proved unreliable in the past.

One way around this is to use independent methods of measuring the cosmic-expansion rate. Among the most promising is analysis of gravitational waves – the ripples in space and time formed by incredibly violent events such as the merger of two massive stars.

Days before last month's meeting, the journal Nature Astronomy published an estimate of the cosmic-expansion rate based on analysis of gravitational waves detected from such an event in 2017.

Unfortunately, it’s still too rough and ready to resolve the paradox of the Methuselah star or the mystery of the two cosmic ages.

In the meantime, theorists have been busy dreaming up new physics that might solve the problem. And in another case of history repeating itself, one of the leading ideas is the “force-from-nowhere” dreamt up by Prof Hoyle, who was later knighted.

Astronomers already think this so-called Dark Energy played a critical role in the Big Bang – although they still have no idea where it came from.

But with one leading astronomer at last month’s meeting describing the current impasse as a scientific crisis, the time may have come to think the unthinkable.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK