Anyone in Muscat who has struggled with their internet connection might find things improve soon.

Late last year, funding was approved for an ambitious project to give more than 400,000 homes and premises in the Omani capital access to fibre optic broadband.

Thousands of miles of cable will be laid by the end of 2021, with 80 per cent of the city to become “fibre ready” in the first phase of a national rollout.

The project's significance goes beyond providing residents with the chance to enjoy Netflix or YouTube uninterrupted; the hope is that fibre optic broadband will make Oman attractive for logistics or manufacturing operations.

This should promote economic diversification, an important goal in a country where hydrocarbons provide almost three-quarters of government revenue.

Funding is coming from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a Chinese-initiated organisation of which the UAE was a founding member. The Articles of Agreement, the legal framework of the bank, were signed on June 29, 2015 by 50 of the named 57 prospective founding members in Beijing, while the other seven signed later. The UAE has contributed $1.18 billion (Dh4.3bn), according to national news agency WAM.

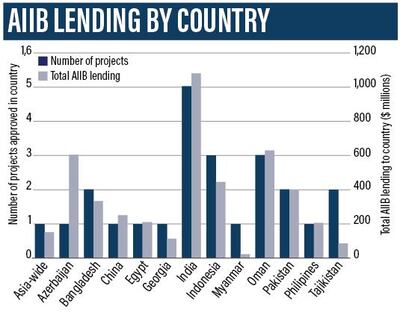

Since its 2016 official launch, the AIIB has agreed to back 28 projects, another of which involves improving port infrastructure in a special economic zone in Oman.

The need for such funding is well acknowledged: estimates suggest Asia will require more than $20 trillion in infrastructure spending over the next two decades or so, and existing lenders cannot get near to supplying all the funds necessary for risky projects that the private sector or national governments balk at supporting.

But for all the acknowledged demand for such finance, the AIIB's creation has not been without controversy.

The organisation was seen, especially early in its genesis, as China's answer to the dominant western-led financial institutions, Beijing's attempt to challenge the "|Washington Consensus". These are the principles of free-trade and development promoted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank since they were founded at the end of the Second World War.

Concerns were raised that the AIIB would fund projects without conditions linked to environmental protection, human rights, labour rights and the like, which finance from the established organisations – of which the Japanese-led Asian Development Bank is another example – often comes with.

China could, it was feared, use the AIIB to hand funds to allies and to advance its strategic interests by supporting projects with potential dual civilian and military applications.

“The AIIB might make its loans based on the 'Beijing Consensus', a competing ideological view with the Washington Consensus … Moreover, the AIIB may represent the first step in China displacing the United States as the final arbiter of the rules of international trade,” wrote Professor Daniel Chow, a business law specialist at the Ohio State University, in early 2016.

Beijing's decision to set up the AIIB is widely thought to result from the lack of reforms in organisations such as the IMF that would have given China, now the world's second-largest economy, and other developing nations more of a say in its running. Despite the support of more than 150 countries and the then US president Barack Obama, reforms fell by the wayside because approval was not forthcoming from the US Congress.

When Beijing reacted by conceiving the AIIB, Washington – worried that the new organisation would erode its global economic influence – urged allies to not to join. It was a plea that many did not heed, including the several Arabian Gulf states that had signed up in 2015.

The March 2015 announcement that one of the US' closest allies, the UK, was joining was seen as key to the decision of many others to sign up. The UAE was among the nations to follow hot on the heels of London's decision.

The Abu Dhabi Fund for Development was nominated to represent the UAE on the AIIB board.

When it comes to the US-allied Gulf states joining, which included Kuwait and Saudi Arabia among others, David Roberts, a specialist in the defence and politics of the Gulf region at King's College London, said the question to ask was, “Why wouldn't they?” He indicated that they have to consider the views of not just Washington, but of other major powers, too.

“There's a notion of balance in there … It strikes me as a fairly sensible thing they should invest in,” said Mr Roberts.

Other major US allies such as France, Germany and South Korea also signed up, bringing the number to 57 by the time the AIIB launched in January 2016 with $100bn of funds, nearly 30 per cent from China. The tally of countries that are members or approved for membership recently reached 87 when Lebanon signed up.

________________

Read more:

UAE signs up as founding member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

Donald Trump may be a challenge for the AIIB

Thousands of foreign workers in Oman go unpaid as contract shortages begin to bite

________________

Now, almost five years since the Chinese president Xi Jinping announced plans to create the AIIB, the organisation has, said Professor Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), largely confounded concerns over how it would operate.

Part of the reason for this could be that the AIIB has a diverse membership and management: the president, Jin Liqun, is Chinese, but the vice presidents are British, French, German, Indian and Indonesian.

“It's a development bank. It's helping the other countries to build their infrastructure and developments that they cannot afford, with good due diligence being conducted,” said Prof Tsang.

Observers have noted that schemes it has supported have typically involved standard development work, and more than one third have the World Bank as the lead investor.

The largest number of projects to receive funding are in India, which analysts have pointed out is democratic and a strategic rival of China.

Other recipients as well as Oman include Indonesia (an irrigation project), Philippines (flood management), Egypt (solar power), Tajikistan (hydroelectric power), Myanmar (a gas-fired power plant) and two Nato allies, Georgia (a bypass road) and Turkey (gas storage). China itself has been awarded funds to alleviate Beijing's severe air pollution by providing villages near the city with gas connections to reduce coal burning.

The total amount of funds allocated so far has fallen short of initial targets, totalling less than $4.5bn over the first two years, compared to initial forecasts of $10bn plus annually. Prof Tsang suggested this could be because the organisation was carrying out careful due diligence.

The rate at which projects are being given the green light appears to be accelerating, and the bank has just agreed a new model for approvals that is designed to improve efficiency while holding senior officials accountable.

In being a Chinese-initiated organisation that has adopted an approach largely consistent with that of institutions led by the West or its allies, the AIIB is, said Prof Tsang, “exceptional”.

“Find me another example where the Chinese created an organisation that is completely following international best practice,” he said.

“It's the only totally successful Chinese-created [institution] that delivers soft power … It may be replicated [in future], but we don't know.”

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

Zayed Sustainability Prize

'Jurassic%20World%20Dominion'

%3Cp%3EDirector%3A%20Colin%20Trevorrow%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EStars%3A%20Sam%20Neill%2C%20Laura%20Dern%2C%20Jeff%20Goldblum%2C%20Bryce%20Dallas%20Howard%2C%20Chris%20Pratt%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ERating%3A%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

More on Quran memorisation:

More on animal trafficking

MOUNTAINHEAD REVIEW

Starring: Ramy Youssef, Steve Carell, Jason Schwartzman

Director: Jesse Armstrong

Rating: 3.5/5

Squad

Ali Kasheif, Salim Rashid, Khalifa Al Hammadi, Khalfan Mubarak, Ali Mabkhout, Omar Abdulrahman, Mohammed Al Attas, Abdullah Ramadan, Zayed Al Ameri (Al Jazira), Mohammed Al Shamsi, Hamdan Al Kamali, Mohammed Barghash, Khalil Al Hammadi (Al Wahda), Khalid Essa, Mohammed Shaker, Ahmed Barman, Bandar Al Ahbabi (Al Ain), Al Hassan Saleh, Majid Suroor (Sharjah) Walid Abbas, Ahmed Khalil (Shabab Al Ahli), Tariq Ahmed, Jasim Yaqoub (Al Nasr), Ali Saleh, Ali Salmeen (Al Wasl), Hassan Al Muharami (Baniyas)

More on Quran memorisation:

More from Neighbourhood Watch

RACE CARD

6.30pm: Madjani Stakes Group 2 (PA) Dh97,500 (Dirt) 1,900m

7.05pm: Maiden (TB) Dh82,500 (D) 1,400m

7.40pm: Maiden (TB) Dh82,500 (D) 1,600m

8.15pm: Handicap (TB) Dh87,500 (D) 2,200m

8.50pm: Dubai Creek Mile Listed (TB) Dh132,500 (D) 1,600m

9.25pm: Conditions (TB) Dh120,000 (D) 1,900m

10pm: Handicap (TB) Dh92,500 (D) 1,400m

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

Scoreline

Saudi Arabia 1-0 Japan

Saudi Arabia Al Muwallad 63’

MATCH INFO

Euro 2020 qualifier

Fixture: Liechtenstein v Italy, Tuesday, 10.45pm (UAE)

TV: Match is shown on BeIN Sports

The five pillars of Islam

IPL 2018 FINAL

Sunrisers Hyderabad 178-6 (20 ovs)

Chennai Super Kings 181-2 (18.3 ovs)

Chennai win by eight wickets

World%20Food%20Day%20

%3Cp%3ECelebrated%20on%20October%2016%2C%20to%20coincide%20with%20the%20founding%20date%20of%20the%20United%20Nations%20Food%20and%20Agriculture%20Organisation%2C%20World%20Food%20Day%20aims%20to%20tackle%20issues%20such%20as%20hunger%2C%20food%20security%2C%20food%20waste%20and%20the%20environmental%20impact%20of%20food%20production.%20%0D%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

FIXTURES

Thursday

Dibba v Al Dhafra, Fujairah Stadium (5pm)

Al Wahda v Hatta, Al Nahyan Stadium (8pm)

Friday

Al Nasr v Ajman, Zabeel Stadium (5pm)

Al Jazria v Al Wasl, Mohammed Bin Zayed Stadium (8pm)

Saturday

Emirates v Al Ain, Emirates Club Stadium (5pm)

Sharjah v Shabab Al Ahli Dubai, Sharjah Stadium (8pm)

List of alleged parties

May 12, 2020: PM and his wife Carrie attend 'work meeting' with at least 17 staff

May 20, 2020: They attend 'bring your own booze party'

Nov 27, 2020: PM gives speech at leaving party for his staff

Dec 10, 2020: Staff party held by then-education secretary Gavin Williamson

Dec 13, 2020: PM and his wife throw a party

Dec 14, 2020: London mayoral candidate Shaun Bailey holds staff event at Conservative Party headquarters

Dec 15, 2020: PM takes part in a staff quiz

Dec 18, 2020: Downing Street Christmas party

Mohammed bin Zayed Majlis

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

KILLING OF QASSEM SULEIMANI

THE BIO

Favourite book: ‘Purpose Driven Life’ by Rick Warren

Favourite travel destination: Switzerland

Hobbies: Travelling and following motivational speeches and speakers

Favourite place in UAE: Dubai Museum

Fixtures

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EWednesday%2C%20April%203%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EArsenal%20v%20Luton%20Town%2C%2010.30pm%20(UAE)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EManchester%20City%20v%20Aston%20Villa%2C%2011.15pm%20(UAE)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EThursday%2C%20April%204%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3ELiverpool%20v%20Sheffield%20United%2C%2010.30pm%20(UAE)%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

If you go:

The flights: Etihad, Emirates, British Airways and Virgin all fly from the UAE to London from Dh2,700 return, including taxes

The tours: The Tour for Muggles usually runs several times a day, lasts about two-and-a-half hours and costs £14 (Dh67)

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child is on now at the Palace Theatre. Tickets need booking significantly in advance

Entrance to the Harry Potter exhibition at the House of MinaLima is free

The hotel: The grand, 1909-built Strand Palace Hotel is in a handy location near the Theatre District and several of the key Harry Potter filming and inspiration sites. The family rooms are spacious, with sofa beds that can accommodate children, and wooden shutters that keep out the light at night. Rooms cost from £170 (Dh808).

Brief scores:

Manchester City 3

Aguero 1', 44', 61'

Arsenal 1

Koscielny 11'

Man of the match: Sergio Aguero (Manchester City)

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

More from Neighbourhood Watch:

Should late investors consider cryptocurrencies?

Wealth managers recommend late investors to have a balanced portfolio that typically includes traditional assets such as cash, government and corporate bonds, equities, commodities and commercial property.

They do not usually recommend investing in Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies due to the risk and volatility associated with them.

“It has produced eye-watering returns for some, whereas others have lost substantially as this has all depended purely on timing and when the buy-in was. If someone still has about 20 to 25 years until retirement, there isn’t any need to take such risks,” Rupert Connor of Abacus Financial Consultant says.

He adds that if a person is interested in owning a business or growing a property portfolio to increase their retirement income, this can be encouraged provided they keep in mind the overall risk profile of these assets.

Zayed Sustainability Prize

The%20specs

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEngine%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204.4-litre%20twin-turbo%20V8%20with%2048V%20mild%20hybrid%20system%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPower%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E544hp%20at%205%2C500rpm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETorque%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E750Nm%20at%201%2C800-5%2C000rpm%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETransmission%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E8-speed%20auto%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPrice%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3Efrom%20Dh700%2C000%20(estimate)%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EOn%20sale%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3Elate%20November%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

KILLING OF QASSEM SULEIMANI

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

Zayed Sustainability Prize

More on Turkey's Syria offence

The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable

Amitav Ghosh, University of Chicago Press

RedCrow Intelligence Company Profile

Started: 2016

Founders: Hussein Nasser Eddin, Laila Akel, Tayeb Akel

Based: Ramallah, Palestine

Sector: Technology, Security

# of staff: 13

Investment: $745,000

Investors: Palestine’s Ibtikar Fund, Abu Dhabi’s Gothams and angel investors

If you go

The flights

Emirates and Etihad fly direct to Nairobi, with fares starting from Dh1,695. The resort can be reached from Nairobi via a 35-minute flight from Wilson Airport or Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, or by road, which takes at least three hours.

The rooms

Rooms at Fairmont Mount Kenya range from Dh1,870 per night for a deluxe room to Dh11,000 per night for the William Holden Cottage.

The specs: 2019 Haval H6

Price, base: Dh69,900

Engine: 2.0-litre turbocharged four-cylinder

Transmission: Seven-speed automatic

Power: 197hp @ 5,500rpm

Torque: 315Nm @ 2,000rpm

Fuel economy, combined: 7.0L / 100km

EA Sports FC 25

Developer: EA Vancouver, EA Romania

Publisher: EA Sports

Consoles: Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4&5, Xbox One and Xbox Series X/S

Rating: 3.5/5

Know your Camel lingo

The bairaq is a competition for the best herd of 50 camels, named for the banner its winner takes home

Namoos - a word of congratulations reserved for falconry competitions, camel races and camel pageants. It best translates as 'the pride of victory' - and for competitors, it is priceless

Asayel camels - sleek, short-haired hound-like racers

Majahim - chocolate-brown camels that can grow to weigh two tonnes. They were only valued for milk until camel pageantry took off in the 1990s

Millions Street - the thoroughfare where camels are led and where white 4x4s throng throughout the festival

The burning issue

The internal combustion engine is facing a watershed moment – major manufacturer Volvo is to stop producing petroleum-powered vehicles by 2021 and countries in Europe, including the UK, have vowed to ban their sale before 2040. The National takes a look at the story of one of the most successful technologies of the last 100 years and how it has impacted life in the UAE.

Read part four: an affection for classic cars lives on

Read part three: the age of the electric vehicle begins

Read part one: how cars came to the UAE

Where to donate in the UAE

The Emirates Charity Portal

You can donate to several registered charities through a “donation catalogue”. The use of the donation is quite specific, such as buying a fan for a poor family in Niger for Dh130.

The General Authority of Islamic Affairs & Endowments

The site has an e-donation service accepting debit card, credit card or e-Dirham, an electronic payment tool developed by the Ministry of Finance and First Abu Dhabi Bank.

Al Noor Special Needs Centre

You can donate online or order Smiles n’ Stuff products handcrafted by Al Noor students. The centre publishes a wish list of extras needed, starting at Dh500.

Beit Al Khair Society

Beit Al Khair Society has the motto “From – and to – the UAE,” with donations going towards the neediest in the country. Its website has a list of physical donation sites, but people can also contribute money by SMS, bank transfer and through the hotline 800-22554.

Dar Al Ber Society

Dar Al Ber Society, which has charity projects in 39 countries, accept cash payments, money transfers or SMS donations. Its donation hotline is 800-79.

Dubai Cares

Dubai Cares provides several options for individuals and companies to donate, including online, through banks, at retail outlets, via phone and by purchasing Dubai Cares branded merchandise. It is currently running a campaign called Bookings 2030, which allows people to help change the future of six underprivileged children and young people.

Emirates Airline Foundation

Those who travel on Emirates have undoubtedly seen the little donation envelopes in the seat pockets. But the foundation also accepts donations online and in the form of Skywards Miles. Donated miles are used to sponsor travel for doctors, surgeons, engineers and other professionals volunteering on humanitarian missions around the world.

Emirates Red Crescent

On the Emirates Red Crescent website you can choose between 35 different purposes for your donation, such as providing food for fasters, supporting debtors and contributing to a refugee women fund. It also has a list of bank accounts for each donation type.

Gulf for Good

Gulf for Good raises funds for partner charity projects through challenges, like climbing Kilimanjaro and cycling through Thailand. This year’s projects are in partnership with Street Child Nepal, Larchfield Kids, the Foundation for African Empowerment and SOS Children's Villages. Since 2001, the organisation has raised more than $3.5 million (Dh12.8m) in support of over 50 children’s charities.

Noor Dubai Foundation

Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum launched the Noor Dubai Foundation a decade ago with the aim of eliminating all forms of preventable blindness globally. You can donate Dh50 to support mobile eye camps by texting the word “Noor” to 4565 (Etisalat) or 4849 (du).

Panipat

Director Ashutosh Gowariker

Produced Ashutosh Gowariker, Rohit Shelatkar, Reliance Entertainment

Cast Arjun Kapoor, Sanjay Dutt, Kriti Sanon, Mohnish Behl, Padmini Kolhapure, Zeenat Aman

Rating 3 /5 stars

More coverage from the Future Forum

RESULTS

Bantamweight title:

Vinicius de Oliveira (BRA) bt Xavier Alaoui (MAR)

(KO round 2)

Catchweight 68kg:

Sean Soriano (USA) bt Noad Lahat (ISR)

(TKO round 1)

Middleweight:

Denis Tiuliulin (RUS) bt Juscelino Ferreira (BRA)

(TKO round 1)

Lightweight:

Anas Siraj Mounir (MAR) bt Joachim Tollefsen (DEN)

(Unanimous decision)

Catchweight 68kg:

Austin Arnett (USA) bt Daniel Vega (MEX)

(TKO round 3)

Lightweight:

Carrington Banks (USA) bt Marcio Andrade (BRA)

(Unanimous decision)

Catchweight 58kg:

Corinne Laframboise (CAN) bt Malin Hermansson (SWE)

(Submission round 2)

Bantamweight:

Jalal Al Daaja (CAN) bt Juares Dea (CMR)

(Split decision)

Middleweight:

Mohamad Osseili (LEB) bt Ivan Slynko (UKR)

(TKO round 1)

Featherweight:

Tarun Grigoryan (ARM) bt Islam Makhamadjanov (UZB)

(Unanimous decision)

Catchweight 54kg:

Mariagiovanna Vai (ITA) bt Daniella Shutov (ISR)

(Submission round 1)

Middleweight:

Joan Arastey (ESP) bt Omran Chaaban (LEB)

(Unanimous decision)

Welterweight:

Bruno Carvalho (POR) bt Souhil Tahiri (ALG)

(TKO)

Suggested picnic spots

Abu Dhabi

Umm Al Emarat Park

Yas Gateway Park

Delma Park

Al Bateen beach

Saadiyaat beach

The Corniche

Zayed Sports City

Dubai

Kite Beach

Zabeel Park

Al Nahda Pond Park

Mushrif Park

Safa Park

Al Mamzar Beach Park

Al Qudrah Lakes

The five pillars of Islam

Lexus LX700h specs

Engine: 3.4-litre twin-turbo V6 plus supplementary electric motor

Power: 464hp at 5,200rpm

Torque: 790Nm from 2,000-3,600rpm

Transmission: 10-speed auto

Fuel consumption: 11.7L/100km

On sale: Now

Price: From Dh590,000

Voy!%20Voy!%20Voy!

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Omar%20Hilal%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Muhammad%20Farrag%2C%20Bayoumi%20Fouad%2C%20Nelly%20Karim%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%204%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

More from Neighbourhood Watch:

The five pillars of Islam

COMPANY PROFILE

Name: Xpanceo

Started: 2018

Founders: Roman Axelrod, Valentyn Volkov

Based: Dubai, UAE

Industry: Smart contact lenses, augmented/virtual reality

Funding: $40 million

Investor: Opportunity Venture (Asia)

Specs

Engine: Dual-motor all-wheel-drive electric

Range: Up to 610km

Power: 905hp

Torque: 985Nm

Price: From Dh439,000

Available: Now

More from Neighbourhood Watch:

Who has been sanctioned?

Daniella Weiss and Nachala

Described as 'the grandmother of the settler movement', she has encouraged the expansion of settlements for decades. The 79 year old leads radical settler movement Nachala, whose aim is for Israel to annex Gaza and the occupied West Bank, where it helps settlers built outposts.

Harel Libi & Libi Construction and Infrastructure

Libi has been involved in threatening and perpetuating acts of aggression and violence against Palestinians. His firm has provided logistical and financial support for the establishment of illegal outposts.

Zohar Sabah

Runs a settler outpost named Zohar’s Farm and has previously faced charges of violence against Palestinians. He was indicted by Israel’s State Attorney’s Office in September for allegedly participating in a violent attack against Palestinians and activists in the West Bank village of Muarrajat.

Coco’s Farm and Neria’s Farm

These are illegal outposts in the West Bank, which are at the vanguard of the settler movement. According to the UK, they are associated with people who have been involved in enabling, inciting, promoting or providing support for activities that amount to “serious abuse”.

KEY DEVELOPMENTS IN MARITIME DISPUTE

2000: Israel withdraws from Lebanon after nearly 30 years without an officially demarcated border. The UN establishes the Blue Line to act as the frontier.

2007: Lebanon and Cyprus define their respective exclusive economic zones to facilitate oil and gas exploration. Israel uses this to define its EEZ with Cyprus

2011: Lebanon disputes Israeli-proposed line and submits documents to UN showing different EEZ. Cyprus offers to mediate without much progress.

2018: Lebanon signs first offshore oil and gas licencing deal with consortium of France’s Total, Italy’s Eni and Russia’s Novatek.

2018-2019: US seeks to mediate between Israel and Lebanon to prevent clashes over oil and gas resources.

Cricket World Cup League Two

Oman, UAE, Namibia

Al Amerat, Muscat

Results

Oman beat UAE by five wickets

UAE beat Namibia by eight runs

Fixtures

Wednesday January 8 –Oman v Namibia

Thursday January 9 – Oman v UAE

Saturday January 11 – UAE v Namibia

Sunday January 12 – Oman v Namibia

Defence review at a glance

• Increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2027 but given “turbulent times it may be necessary to go faster”

• Prioritise a shift towards working with AI and autonomous systems

• Invest in the resilience of military space systems.

• Number of active reserves should be increased by 20%

• More F-35 fighter jets required in the next decade

• New “hybrid Navy” with AUKUS submarines and autonomous vessels

The years Ramadan fell in May

The%20end%20of%20Summer

%3Cp%3EAuthor%3A%20Salha%20Al%20Busaidy%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EPages%3A%20316%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3EPublisher%3A%20The%20Dreamwork%20Collective%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

'The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window'

Director:Michael Lehmann

Stars:Kristen Bell

Rating: 1/5

MATCH INFO

AC Milan v Inter, Sunday, 6pm (UAE), match live on BeIN Sports

RESULT

Argentina 0 Croatia 3

Croatia: Rebic (53'), Modric (80'), Rakitic (90' 1)

Killing of Qassem Suleimani

Roll of honour

Who has won what so far in the West Asia Premiership season?

Western Clubs Champions League - Winners: Abu Dhabi Harlequins; Runners up: Bahrain

Dubai Rugby Sevens - Winners: Dubai Exiles; Runners up: Jebel Ali Dragons

West Asia Premiership - Winners: Jebel Ali Dragons; Runners up: Abu Dhabi Harlequins

UAE Premiership Cup - Winners: Abu Dhabi Harlequins; Runners up: Dubai Exiles

West Asia Cup - Winners: Bahrain; Runners up: Dubai Exiles

West Asia Trophy - Winners: Dubai Hurricanes; Runners up: DSC Eagles

Final West Asia Premiership standings - 1. Jebel Ali Dragons; 2. Abu Dhabi Harlequins; 3. Bahrain; 4. Dubai Exiles; 5. Dubai Hurricanes; 6. DSC Eagles; 7. Abu Dhabi Saracens

Fixture (UAE Premiership final) - Friday, April 13, Al Ain – Dubai Exiles v Abu Dhabi Harlequins

The specs

Engine: 2-litre or 3-litre 4Motion all-wheel-drive Power: 250Nm (2-litre); 340 (3-litre) Torque: 450Nm Transmission: 8-speed automatic Starting price: From Dh212,000 On sale: Now

RESULTS

5pm: Maiden (PA) Dh80,000 1,200m

Winner: Ferdous, Szczepan Mazur (jockey), Ibrahim Al Hadhrami (trainer)

5.30pm: Arabian Triple Crown Round-3 Group 3 (PA) Dh300,000 2,400m

Winner: Basmah, Fabrice Veron, Eric Lemartinel

6pm: UAE Arabian Derby Prestige (PA) Dh150,000 2,200m

Winner: Ihtesham, Szczepan Mazur, Ibrahim Al Hadhrami

6.30pm: Emirates Championship Group 1 (PA) Dh1,000,000 2,200m

Winner: Somoud, Patrick Cosgrave, Ahmed Al Mehairbi

7pm: Abu Dhabi Championship Group 3 (TB) Dh380,000 2,200m

Winner: GM Hopkins, Patrick Cosgrave, Jaber Ramadhan

7.30pm: Wathba Stallions Cup Conditions (PA) Dh70,000 1,600m

Winner: AF Al Bairaq, Tadhg O’Shea, Ernst Oertel

The stats

Ship name: MSC Bellissima

Ship class: Meraviglia Class

Delivery date: February 27, 2019

Gross tonnage: 171,598 GT

Passenger capacity: 5,686

Crew members: 1,536

Number of cabins: 2,217

Length: 315.3 metres

Maximum speed: 22.7 knots (42kph)

UAE currency: the story behind the money in your pockets

More from Neighbourhood Watch

Read more about the coronavirus