The US condemned on Friday comments by a Taliban official who said the group would restore the use of amputations and executions as punishment in Afghanistan, State Department spokesperson Ned Price said.

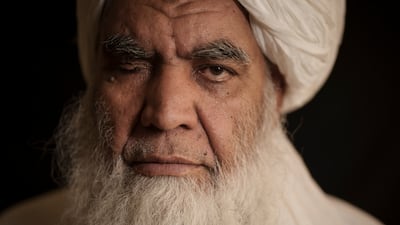

Mr Price responded to Taliban leader Mullah Nooruddin Turabi's comments to the AP, saying the punishments "would constitute clear gross abuses of human rights".

"We stand firm with the international community to hold perpetrators of these, of any such abuses, accountable," Reuters cited Mr Price as saying.

Washington said any potential recognition of the new Taliban-led government in Kabul, which replaced the western-backed government that collapsed last month, would depend on respect for human rights.

"We are watching very closely," Mr Price said, "and not just listening to the announcements that come out but watching very closely as the Taliban conducts itself".

Since the Taliban overran Kabul on August 15 and seized control of the country, Afghans and the world have been watching to see whether they will recreate their harsh rule of the late 1990s.

Turabi’s comments pointed to how the group’s leaders remain entrenched in a deeply conservative, hardline worldview, even if they are embracing technological changes, like video and mobile phones.

Turabi, now in his early 60s, was justice minister and head of the so-called Ministry of Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice – effectively, the religious police – during the Taliban’s previous rule.

At that time, the world denounced the Taliban’s punishments, which took place in Kabul’s sports stadium or on the grounds of the sprawling Eid Gah mosque, often attended by hundreds of Afghan men.

Executions of convicted murderers were usually by a single shot to the head, carried out by the victim’s family, who had the option of accepting “blood money” and allowing the culprit to live.

For convicted thieves, the punishment was amputation of a hand. For those convicted of highway robbery, a hand and a foot were amputated.

Trials and convictions were rarely public and the judiciary was weighted in favor of Islamic clerics, whose knowledge of the law was limited to religious injunctions.

Turabi said this time, judges – including women – would adjudicate cases, but the foundation of Afghanistan’s laws will be the Quran. He said the same punishments would be revived.

“Cutting off of hands is very necessary for security,” he said, saying it had a deterrent effect. He said the Cabinet was studying whether to carry out punishments in public and will “develop a policy”.

Under the previous government, no death sentences were carried out between 2001 and 2004 despite a 1976 penal code remaining in effect, which would have permitted executions for murder, treason or rape.

Capital punishment resumed in 2004 following a surge in violence and, despite several short-lived moratoriums on the death penalty, mass executions – usually of Taliban prisoners, were not uncommon.

This policy was widely criticised by human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch and the Open Society Foundation, who blamed the Afghan government of using torture to extract confessions.

Cases where suspects were considered to have intentionally killed civilians, usually in high profile attacks, were categorised as mass murder.

Unlike during the 1996-2001 Taliban rule, executions were not public and in some cases defendants could appeal to a supreme court. Article 129 of the constitution stipulated that the president would sign off on all executions, which would lead to a second appeal process.