There are 274 million people worldwide who will need emergency aid and protection in 2022, a 17 per cent increase compared with last year, which was already the highest figure in decades, UN humanitarians said on Thursday.

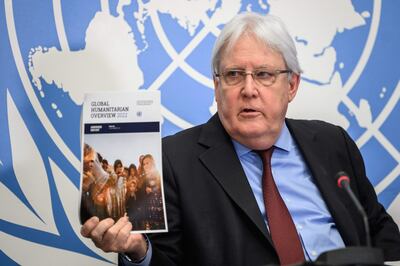

The amount is equivalent to “the world’s fourth most populous country”, Martin Griffiths, UN Humanitarian Affairs chief said at the launch of the 2022 Global Humanitarian Overview (GHO) in Geneva.

The GHO is the world’s most comprehensive and evidence-based assessment of humanitarian need issued annually by the UN’s humanitarian bodies.

An estimated $41 billion is required in urgent relief funds for 183 million people in 63 countries that are most in need, according to the report.

Two regions, the Middle East and North Africa and West and Central Africa, have the most pressing humanitarian need because of protracted crises that show no signs of abating.

Famine is a terrifying prospect for 45 million people in 43 countries. More than 1 per cent of the world’s population are displaced, about 42 per cent of whom are children.

Millions of internally displaced people are living in protracted situations, 40 per cent of whom are unable to return home. Women and girls suffer the most in crisis areas as risks increase.

“Children, especially girls, are missing out on their education. Women’s rights are threatened,” Mr Griffiths said.

Extreme poverty is rising and food insecurity is at unprecedented levels. Globally, up to 811 million people are undernourished.

“Without sustained and immediate action, 2022 could be catastrophic,” the UN said in its appeal.

The Covid-19 pandemic is also taking a heavy toll in developing countries, claiming at least 1.8 million lives across the GHO countries, fuelled by variants and a lack of vaccines.

Worst hit

Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, Ethiopia and Sudan were the five countries worst affected with the highest aid needs.

Afghanistan needs $4.5 billion in relief funds in 2022. Syria comes next with $4.2 billion, Yemen with $3.9 billion, Ethiopia with $2.8 billion and Sudan with $1.9 billion.

In Afghanistan more than 24 million people require life-saving assistance to prevent catastrophe.

“Needs are skyrocketing. I saw systems on the brink of complete collapse and the rights of women and girls under threat,” Mr Griffiths said of the war-ravaged country.

He also pointed out that aid agencies “never left Afghanistan, in the wake of August’s Taliban takeover. We have a programme for 2022, three times the size of the programme for 2021 because of the needs”.

In Ethiopia, climate shocks, high levels of conflict, insecurity and disease outbreaks coupled with a deteriorating economy continue to exacerbate humanitarian needs for 25.9 million people.

“New battlefields have emerged, including in northern Ethiopia, where millions now need aid to survive. Across Ethiopia, humanitarian needs are growing at an alarming rate,” Mr Griffiths said.

Besides the conflict, drought and locust swarms are pushing more people to the brink.

Health care was delivered to 10 million people in Yemen and hundreds of millions of dollars were dispersed in cash assistance, “so kept famine at bay”, Mr Griffiths said.

Acute food insecurity is a reality for 16.2 million people in the country. Even with the current levels of humanitarian assistance, 40 per cent of the population have inadequate food.

A decade into the crisis in Syria, basic service delivery is vastly inadequate and hampered by damaged infrastructure, lack of critical supplies and, increasingly, financial unaffordability.

In South Sudan, more than half a million people were brought back from the brink of famine.

The country, according to the UN, is facing its highest levels of food insecurity and malnutrition since it declared independence 10 years ago.

Climate crisis

Climate crisis is no longer a future threat, the relief agencies said, and is fuelling famine and conflicts around the world.

The past six years were the hottest on record, causing heatwaves, droughts, tropical storms and severe floods.

Records show 26 per cent more storms, 23 per cent more floods and 18 per cent more deaths from floods compared with the average.

“The climate crisis is hitting the world’s most vulnerable people first and worst. Protracted conflicts grind on, and instability has worsened in several parts of the world, notably Ethiopia, Myanmar and Afghanistan,” Mr Griffiths said.

"The cost of inaction in the face of these challenges is high," he said.

What vitamins do we know are beneficial for living in the UAE

Vitamin D: Highly relevant in the UAE due to limited sun exposure; supports bone health, immunity and mood.

Vitamin B12: Important for nerve health and energy production, especially for vegetarians, vegans and individuals with absorption issues.

Iron: Useful only when deficiency or anaemia is confirmed; helps reduce fatigue and support immunity.

Omega-3 (EPA/DHA): Supports heart health and reduces inflammation, especially for those who consume little fish.

COMPANY PROFILE

Name: HyperSpace

Started: 2020

Founders: Alexander Heller, Rama Allen and Desi Gonzalez

Based: Dubai, UAE

Sector: Entertainment

Number of staff: 210

Investment raised: $75 million from investors including Galaxy Interactive, Riyadh Season, Sega Ventures and Apis Venture Partners

APPLE IPAD MINI (A17 PRO)

Display: 21cm Liquid Retina Display, 2266 x 1488, 326ppi, 500 nits

Chip: Apple A17 Pro, 6-core CPU, 5-core GPU, 16-core Neural Engine

Storage: 128/256/512GB

Main camera: 12MP wide, f/1.8, digital zoom up to 5x, Smart HDR 4

Front camera: 12MP ultra-wide, f/2.4, Smart HDR 4, full-HD @ 25/30/60fps

Biometrics: Touch ID, Face ID

Colours: Blue, purple, space grey, starlight

In the box: iPad mini, USB-C cable, 20W USB-C power adapter

Price: From Dh2,099

Key facilities

- Olympic-size swimming pool with a split bulkhead for multi-use configurations, including water polo and 50m/25m training lanes

- Premier League-standard football pitch

- 400m Olympic running track

- NBA-spec basketball court with auditorium

- 600-seat auditorium

- Spaces for historical and cultural exploration

- An elevated football field that doubles as a helipad

- Specialist robotics and science laboratories

- AR and VR-enabled learning centres

- Disruption Lab and Research Centre for developing entrepreneurial skills

Pathaan

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Siddharth%20Anand%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Shah%20Rukh%20Khan%2C%20Deepika%20Padukone%2C%20John%20Abraham%C2%A0%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%203%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Profile

Co-founders of the company: Vilhelm Hedberg and Ravi Bhusari

Launch year: In 2016 ekar launched and signed an agreement with Etihad Airways in Abu Dhabi. In January 2017 ekar launched in Dubai in a partnership with the RTA.

Number of employees: Over 50

Financing stage: Series B currently being finalised

Investors: Series A - Audacia Capital

Sector of operation: Transport

Formula Middle East Calendar (Formula Regional and Formula 4)

Round 1: January 17-19, Yas Marina Circuit – Abu Dhabi

Round 2: January 22-23, Yas Marina Circuit – Abu Dhabi

Round 3: February 7-9, Dubai Autodrome – Dubai

Round 4: February 14-16, Yas Marina Circuit – Abu Dhabi

Round 5: February 25-27, Jeddah Corniche Circuit – Saudi Arabia

Europe’s rearming plan

- Suspend strict budget rules to allow member countries to step up defence spending

- Create new "instrument" providing €150 billion of loans to member countries for defence investment

- Use the existing EU budget to direct more funds towards defence-related investment

- Engage the bloc's European Investment Bank to drop limits on lending to defence firms

- Create a savings and investments union to help companies access capital

The biog

Alwyn Stephen says much of his success is a result of taking an educated chance on business decisions.

His advice to anyone starting out in business is to have no fear as life is about taking on challenges.

“If you have the ambition and dream of something, follow that dream, be positive, determined and set goals.

"Nothing and no-one can stop you from succeeding with the right work application, and a little bit of luck along the way.”

Mr Stephen sells his luxury fragrances at selected perfumeries around the UAE, including the House of Niche Boutique in Al Seef.

He relaxes by spending time with his family at home, and enjoying his wife’s India cooking.

Dengue%20fever%20symptoms

%3Cul%3E%0A%3Cli%3EHigh%20fever%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3EIntense%20pain%20behind%20your%20eyes%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3ESevere%20headache%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3EMuscle%20and%20joint%20pains%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3ENausea%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3EVomiting%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3ESwollen%20glands%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3Cli%3ERash%3C%2Fli%3E%0A%3C%2Ful%3E%0A%3Cp%3EIf%20symptoms%20occur%2C%20they%20usually%20last%20for%20two-seven%20days%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

DUNE%3A%20PART%20TWO

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Denis%20Villeneuve%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStarring%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Timothee%20Chamalet%2C%20Zendaya%2C%20Austin%20Butler%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%205%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

The biog

Born November 11, 1948

Education: BA, English Language and Literature, Cairo University

Family: Four brothers, seven sisters, two daughters, 42 and 39, two sons, 43 and 35, and 15 grandchildren

Hobbies: Reading and traveling

RACECARD

6pm Emaar Dubai Sprint – Conditions (TB) $60,000 (Turf) 1,200m

6.35pm Graduate Stakes – Conditions (TB) $100,000 (Dirt) 1,600m

7.10pm Al Khail Trophy – Listed (TB) $100,000 (T) 2,810m

7.45pm UAE 1000 Guineas – Listed (TB) $150,000 (D) 1,600m

8.20pm Zabeel Turf – Listed (TB) $100,000 (T) 2,000m

8.55pm Downtown Dubai Cup – Rated Conditions (TB) $80,000 (D) 1,400m

9.30pm Zabeel Mile – Group 2 (TB) $180,000 (T) 1,600m

10.05pm Dubai Sprint – Listed (TB) $100,000 (T) 1,200m

What is cyberbullying?

Cyberbullying or online bullying could take many forms such as sending unkind or rude messages to someone, socially isolating people from groups, sharing embarrassing pictures of them, or spreading rumors about them.

Cyberbullying can take place on various platforms such as messages, on social media, on group chats, or games.

Parents should watch out for behavioural changes in their children.

When children are being bullied they they may be feel embarrassed and isolated, so parents should watch out for signs of signs of depression and anxiety

Super%20Mario%20Bros%20Wonder

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDeveloper%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENintendo%20EPD%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPublisher%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENintendo%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EConsole%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ENintendo%20Switch%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E4%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

Awar Qalb

Director: Jamal Salem

Starring: Abdulla Zaid, Joma Ali, Neven Madi and Khadija Sleiman

Two stars

More from UAE Human Development Report:

COMPANY%20PROFILE

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EName%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EEjari%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EBased%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ERiyadh%2C%20Saudi%20Arabia%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EFounders%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EYazeed%20Al%20Shamsi%2C%20Fahad%20Albedah%2C%20Mohammed%20Alkhelewy%20and%20Khalid%20Almunif%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ESector%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3EPropTech%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ETotal%20funding%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E%241%20million%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EInvestors%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3ESanabil%20500%20Mena%2C%20Hambro%20Perks'%20Oryx%20Fund%20and%20angel%20investors%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3ENumber%20of%20employees%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E8%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

'HIJRAH%3A%20IN%20THE%20FOOTSTEPS%20OF%20THE%20PROPHET'

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EEdited%20by%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Idries%20Trevathan%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPages%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20240%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EPublisher%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Hirmer%20Publishers%3Cbr%3E%3Cstrong%3EAvailable%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Now%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

How to wear a kandura

Dos

- Wear the right fabric for the right season and occasion

- Always ask for the dress code if you don’t know

- Wear a white kandura, white ghutra / shemagh (headwear) and black shoes for work

- Wear 100 per cent cotton under the kandura as most fabrics are polyester

Don’ts

- Wear hamdania for work, always wear a ghutra and agal

- Buy a kandura only based on how it feels; ask questions about the fabric and understand what you are buying

BLACK%20ADAM

%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EDirector%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Jaume%20Collet-Serra%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3EStars%3A%3C%2Fstrong%3E%20Dwayne%20Johnson%2C%20Sarah%20Shahi%2C%20Viola%20Davis%2C%20Pierce%20Brosnan%3C%2Fp%3E%0A%3Cp%3E%3Cstrong%3ERating%3A%20%3C%2Fstrong%3E3%2F5%3C%2Fp%3E%0A

MATCH INFO

Uefa Champions League semi-final, first leg

Bayern Munich v Real Madrid

When: April 25, 10.45pm kick-off (UAE)

Where: Allianz Arena, Munich

Live: BeIN Sports HD

Second leg: May 1, Santiago Bernabeu, Madrid

'Doctor Strange in the Multiverse Of Madness'

Director: Sam Raimi

Cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Elizabeth Olsen, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Benedict Wong, Xochitl Gomez, Michael Stuhlbarg and Rachel McAdams

Rating: 3/5

What is a robo-adviser?

Robo-advisers use an online sign-up process to gauge an investor’s risk tolerance by feeding information such as their age, income, saving goals and investment history into an algorithm, which then assigns them an investment portfolio, ranging from more conservative to higher risk ones.

These portfolios are made up of exchange traded funds (ETFs) with exposure to indices such as US and global equities, fixed-income products like bonds, though exposure to real estate, commodity ETFs or gold is also possible.

Investing in ETFs allows robo-advisers to offer fees far lower than traditional investments, such as actively managed mutual funds bought through a bank or broker. Investors can buy ETFs directly via a brokerage, but with robo-advisers they benefit from investment portfolios matched to their risk tolerance as well as being user friendly.

Many robo-advisers charge what are called wrap fees, meaning there are no additional fees such as subscription or withdrawal fees, success fees or fees for rebalancing.

SANCTIONED

- Kirill Shamalov, Russia's youngest billionaire and previously married to Putin's daughter Katarina

- Petr Fradkov, head of recently sanctioned Promsvyazbank and son of former head of Russian Foreign Intelligence, the FSB.

- Denis Bortnikov, Deputy President of Russia's largest bank VTB. He is the son of Alexander Bortnikov, head of the FSB which was responsible for the poisoning of political activist Alexey Navalny in August 2020 with banned chemical agent novichok.

- Yury Slyusar, director of United Aircraft Corporation, a major aircraft manufacturer for the Russian military.

- Elena Aleksandrovna Georgieva, chair of the board of Novikombank, a state-owned defence conglomerate.

BEACH SOCCER WORLD CUP

Group A

Paraguay

Japan

Switzerland

USA

Group B

Uruguay

Mexico

Italy

Tahiti

Group C

Belarus

UAE

Senegal

Russia

Group D

Brazil

Oman

Portugal

Nigeria

Farage on Muslim Brotherhood

Nigel Farage told Reform's annual conference that the party will proscribe the Muslim Brotherhood if he becomes Prime Minister.

"We will stop dangerous organisations with links to terrorism operating in our country," he said. "Quite why we've been so gutless about this – both Labour and Conservative – I don't know.

“All across the Middle East, countries have banned and proscribed the Muslim Brotherhood as a dangerous organisation. We will do the very same.”

It is 10 years since a ground-breaking report into the Muslim Brotherhood by Sir John Jenkins.

Among the former diplomat's findings was an assessment that “the use of extreme violence in the pursuit of the perfect Islamic society” has “never been institutionally disowned” by the movement.

The prime minister at the time, David Cameron, who commissioned the report, said membership or association with the Muslim Brotherhood was a "possible indicator of extremism" but it would not be banned.

MATCH RESULT

Liverpool 4 Brighton and Hove Albion 0

Liverpool: Salah (26'), Lovren (40'), Solanke (53'), Robertson (85')